(Source: HartEnergy.com; Lightboxx, Pyty/Shutterstock.com)

The pipeline sector is primed to transport the cleaner fuels of the future but attracting capital has emerged as a huge challenge because of what was termed the “tobaccofication” of the oil and gas industry, members of a North American infrastructure panel said during the recent CERAWeek by IHS Markit virtual conference.

“In terms of equity capital, the markets are severely depressed,” said Peter Bowden, managing director and global head of energy investment banking for Jefferies. “Our view is that most of these companies trade well below where we see intrinsic value.”

In 2013 through 2015, average equity issuance a year for midstream companies was $25 billion, Bowden said. In 2018 through 2020, that average nosedived to $1 billion. MLPs alone were raising about $4 billion a year in the middle of the last decade. Since 2016, they’ve raised effectively zero, he said. Oil and gas has become a social and investing pariah, much like the tobacco industry.

“The reality is that the infrastructure companies have made real returns from a shareholder perspective,” Bowden said. “It’s not a black and white issue—if it’s fossil fuels, it’s bad; if it’s not, it’s good. People confuse all aspects of the energy industry with negative impacts to climate which I think is a blanket conclusion and it’s just simply not factually accurate.”

The conclusion may be simplistic, but it also may be a reflection of an era in which public discourse is not marked by nuance.

“The reality is, these disconnects that we’re talking about, this polarization, have real impacts on public companies today,” Al Monaco, president and CEO of Enbridge Inc., said. “The good news … is the value of the pipe we have in the ground is increasing. We haven’t seen that reflected yet in equity prices but it’s got to get there. You simply can’t replicate this pipe in the ground and it’s going to be generating cash flow for a very long time.”

Clockwise from top left: Moderator Daniel Yergin of IHS Markit; Alan Armstrong of The Williams Cos.; Al Monaco of Enbridge Inc.; and Peter Bowden of Jefferies. (Source: CERAWeek by IHS Markit)

Capital Ideas

But in the near term, it could feel to energy executives like capitalism has passed them by.

“The thing that we forget as energy guys is, look at how much money has been made in health care and tech and other sectors,” Bowden said. It’s not that the buy-side firms and hedge funds abandoned energy because they didn’t make money. It’s just that there’s more money to be made elsewhere.

“Once the 30-person desk focused on energy at the hedge fund becomes a five-person desk or, even worse, a zero-person desk, it no longer matters whether earnings are up and to the right,” he said. “You can perform as a business and, recently, it seems like the public equity markets don’t care much.”

The response, Monaco said, is for companies to focus on how they allocate capital. First, forget greenfield projects—“those are a huge leap,” he said. Instead, prioritize expansions, repurposing and extensions of what the company already has. Then, work from the ground up.

“Before you proceed with a project, you need to establish the value proposition with local communities, regions and cities, in particular,” Monaco said. “That’s a tough one but it’s got to happen.”

A solid level of community support is a must along with an ironclad regulatory and permitting application. The days are past when a company could move a project along and spend money with the assumption of getting a fair shake on the regulatory front, he said.

“When you actually evaluate projects today, you need to reflect a higher cost of capital to reflect these risks, there’s just no doubt about that,” Monaco said. “And that may include carbon price. You’ve got to have more contingency in your capital cost estimate.”

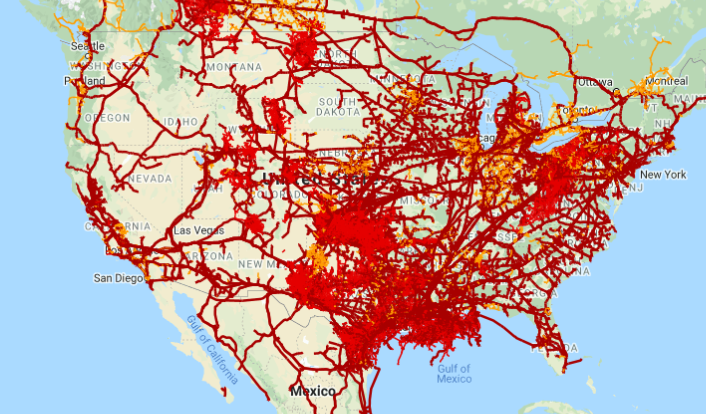

The U.S. Lower 48 natural gas pipeline network. (Source: Rextag Energy Datalink)

Ready or Not

Where the midstream is extremely well-positioned for the energy transition is its national natural gas network of pipelines that can carry hydrogen, as well.

“We see there is a real market in the public’s desire for decarbonization and so where there are opportunities to do that in an economically feasible manner, we’re certainly doing that,” said Alan Armstrong, president and CEO of The Williams Cos. “Our gas pipeline network does allow us to take advantage of excess renewable power.”

What is imperative, Armstrong advised, is moving forward now. Williams’ goal is a 56% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 compared to 2005. While he admitted that he didn’t know which technology would propel the company to that point, he noted that neither do most companies that have made those commitments.

“When you talk about net-zero for 2050, we simply have said that the 2030 goal puts us on a trajectory to get there,” he said. “If you really are serious about greenhouse gas emissions reduction and getting there by 2050, you need to be taking advantage of the tools and the technology we have here today and not waiting on a pie in the sky.”

Transition Plan

If committing to emission reductions by relying on technology that is yet to exist seems nerve-wracking, stepping back to devise a path might be a good choice. Enbridge took two years to develop a model based on supply and demand scenarios to pick its options. The Canadian pipeline company’s goal is net-zero by 2050 and a 35% reduction in energy intensity by 2030 from 2018 levels. Monaco described four pillars:

- Modernizing assets;

- Using new technology, including predictive analytics to optimize power use;

- Employing solar panels to power pumps and compressors; and

- Using Enbridge’s renewables business to provide offsets for use in the rest of the company.

Among the technological challenges is figuring out how to bring hydrogen to a scale in which the cost is comparable to natural gas. At the moment, hydrogen is four to seven times as expensive. It is incompatible with older pipes and requires more compression. On the plus side, Monaco said, hydrogen enjoys plenty of support from government and along the value chain.

Even if hydrogen causes embrittlement problems with steel pipes, it can still be moved in a blend with natural gas. And as far as the atmosphere is concerned, Armstrong said, burning hydrogen either by itself or with natural gas provides an emissions reduction impact.

“The ability to blend 5% into our national grid is an enormous amount of hydrogen, a lot more than people are talking about, actually,” he said. “As an industry, we need to make sure that we are communicating well on that topic and that we’re seizing the opportunity on that.”

Recommended Reading

Energy Transition in Motion (Week of Feb. 2, 2024)

2024-02-02 - Here is a look at some of this week’s renewable energy news, including a utility’s plans to add 3.6 gigawatts of new solar and wind facilities by 2030.

After Challenging Year, Which Way Will Offshore Wind Blow?

2024-04-03 - Following a year of negative headlines with some of the industry’s biggest players booking billion-dollar impairments and backing out of wind projects, this year appears to be going smoother.

First US Utility-scale Offshore Wind Farm Starts Operations

2024-03-14 - The 12-turbine, 130-megawatt South Fork Wind project is a joint venture between Denmark's Orsted and New England-based electric utility Eversource.

Dominion Energy Receives Final Approvals for 2.6-GW Offshore Wind Project

2024-01-30 - Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project will feature 176 turbines and three offshore substations on a nearly 113,000-acre lease area off Virginia Beach.

Energy Transition in Motion (Week of Feb. 23, 2024)

2024-02-23 - Here is a look at some of this week’s renewable energy news, including approval of the construction and operations plan for Empire Wind offshore New York.