Boston represents a hotbed of institutional funds facing pressure to consider ESG in their investments. (Source: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock.com)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the June 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Primary industry activities, whether in farming, mining or drilling for oil and gas, often affect the environment and society. Deciding what level of impact is appropriate is typically set by a region’s regulations or guidelines. For today’s energy sector—a key driver of growth for many economies—the conversation is rapidly broadening as goals are set in pursuit of a low-carbon economy.

[Corp.] alone

has a market

cap that exceeds

every solar and

wind company,

in aggregate,

in the world,”

observed Pavel

Molchanov, senior

vice president

covering the

alternative/clean

technology sector

for Raymond

James &

Associates Inc.

Are such trends influencing worldwide portfolios by tilting them away from energy investments? And is anti-fossil fuel sentiment growing to the point that it’s a factor in overall investment decision-making? How widespread are divestments driven by anti-fossil fuel policies—both now and looking to the future?

The answers depend on who is asked. Some signs, particularly in Europe, point in that direction. Others, more frequently in the U.S., offer a wider spectrum of views, with some reporting little or no impact from anti-fossil fuel sentiment.

The oil and gas sector is a key part of Norway’s economy and is projected to contribute 17% of its GDP in 2019. The sector employs some 170,000 people. However, a recent decision was taken to keep the Lofoten Islands area off-limits from drilling, despite estimates that it holds 5% of total undiscovered resources on the Norwegian continental shelf.

“Climate comes before cash!” was the cry in April from a demonstrator in front of the Norwegian parliament, reflecting the growing anti-fossil fuel sentiment among some of its citizens. A month earlier, Norway’s $1-trillion Government Pension Fund Global declared it would divest its E&P stock holdings.

ESG

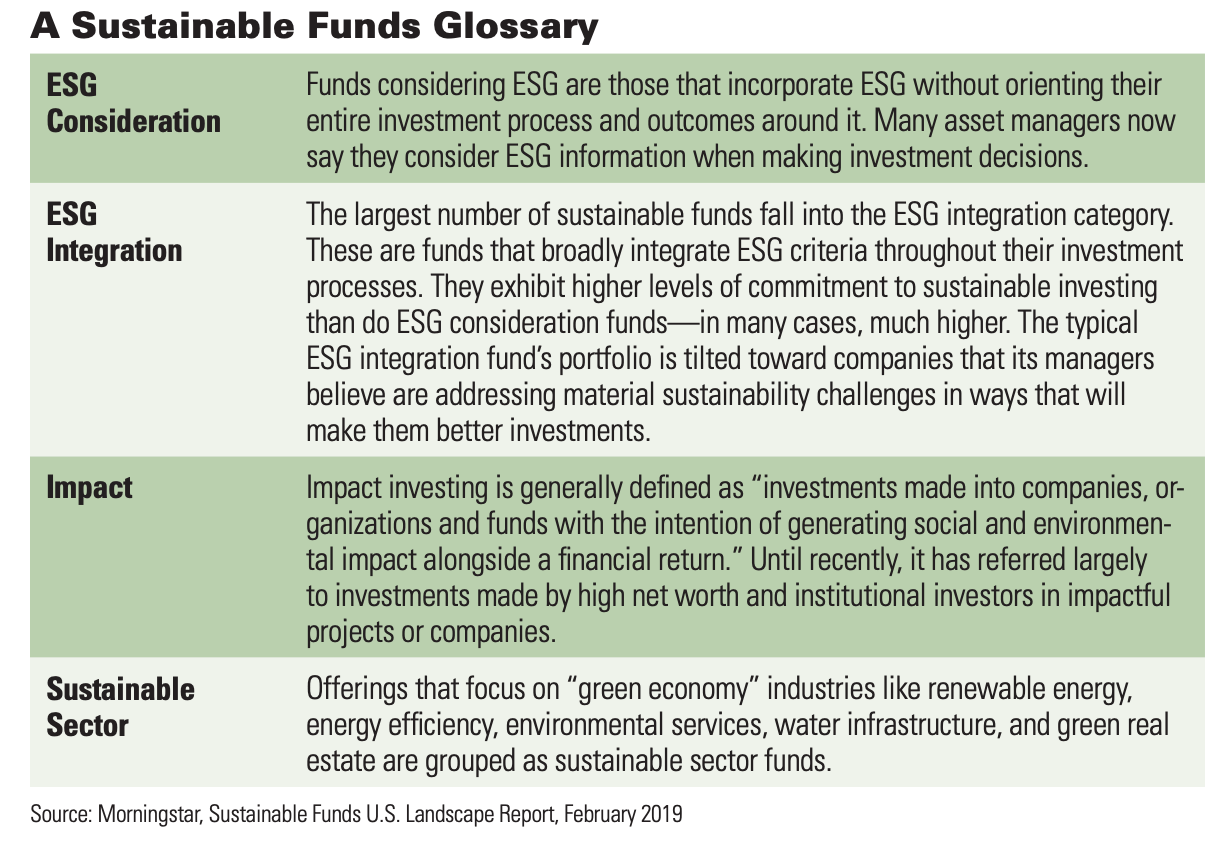

In the U.S., professional asset managers seem to be moving in a similar direction and increasingly offering “sustainable funds” that incorporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations. For example, a recent report by Morningstar estimated that, in 2018, there were 351 sustainable funds, up nearly 50% from 235 in 2017.

“Sustainable investing emphasizes material ESG issues that contribute to a more thorough financial analysis,” according to Morningstar, which provides ratings of mutual funds and other investment vehicles. “It encourages direct investment in areas like renewable energy and green technologies as the world transitions to a low-carbon economy.”

A hard nut to crack is the size of assets in this category: Do you need a sledgehammer or a nutcracker?

According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA), assets under management (AUM) in Europe formed the largest pool of sustainable investment assets, standing at $14.1 trillion at the beginning of 2018. The next-largest pool is in the U.S., with AUM of $12 trillion, having grown markedly from $8.7 trillion at the start of 2016, according to the GSIA.

Trillions of dollars!?

According to Morningstar, AUM from the 351 funds in its report came to $161 billion. Moreover, if the report focused “only on those with the more comprehensive sustainability criteria,” the AUM figure dropped to $89 billion, it reported.

The category’s “AUM and fund flows, though both higher than ever before, remain tiny compared with the overall U.S. fund universe,” it added.

Obviously, much depends on how tightly, or loosely, these various categories of fund assets are defined.

For perspective, if looking to invest in what is broadly called renewable energy, the opportunity set is far from unbounded. As an example, electric power generated in the U.S. by renewables in 2017 made up less than 17% of all electric power, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration data. The renewable sources were 7.4%, hydropower; 6.3%, wind; 1.3%, solar; and 1.6%, biomass.

By contrast, natural gas continues to be the largest power source for electricity in the U.S. The relatively clean-burning fuel accounted for 32.1% of electric power generated in 2017, more than the once top spot held by coal, which stood at 29.9%. Nuclear power—disliked in some environmentalist circles, but favored elsewhere for its low-carbon technology—generated some 20% of electricity.

Growing, But Still Only A ‘Sliver’

“The share of renewables and low-carbon technology is increasing, and, as a result, the market cap of the companies involved in the sector is increasing,” said Pavel Molchanov, senior vice president covering the alternative/clean technology sector for Raymond James & Associates Inc. in Houston. “But renewables are still only a small sliver of the investable energy universe.”

“ExxonMobil [Corp.] alone has a market cap that exceeds every solar and wind company, in aggregate, in the world,” he added.

Molchanov traces the roots of growing anti-fossil fuel sentiment—and its impact on investing—to Europe, which is a new fossil fuel importer.

“The environmental/green movement is more widespread in Europe than anywhere else, and its influence is being felt in the financial sector,” he said. “As far as types of organizations taking part in divestment, most are non-profits: public-sector pension funds and university or church endowments.

“However, three of the top four are financial-services firms, so the private sector is playing a role as well.”

A Raymond James study published last August of institutions divesting of fossil fuel holdings showed the top four, with AUM ranging from $800 billion up to $1.9 trillion, to all be based in Europe. All four committed to divesting their coal-sector holdings, while two of the four additionally pledged to move out of oil-sands investments. The divestment process began two to four years ago.

are nervous

about possible

legislation on

climate change

arising over the

next 20 years,”

said Robert

Plummer, vice

president with

energy research

and consulting

firm Wood

Mackenzie.

Taking a broader view, encompassing all divestment plans—not just the top four—Raymond James estimated assets subject to divestment at less than $50 billion. This was based on aggregate AUM of institutions with divestment plans ($4- to $5 trillion), an assumed energy weighting in line with the S&P 500 and MSCI World Index (6% to 7%) and more than 80% of divestments concentrated in the narrower coal and oil-sands segments.

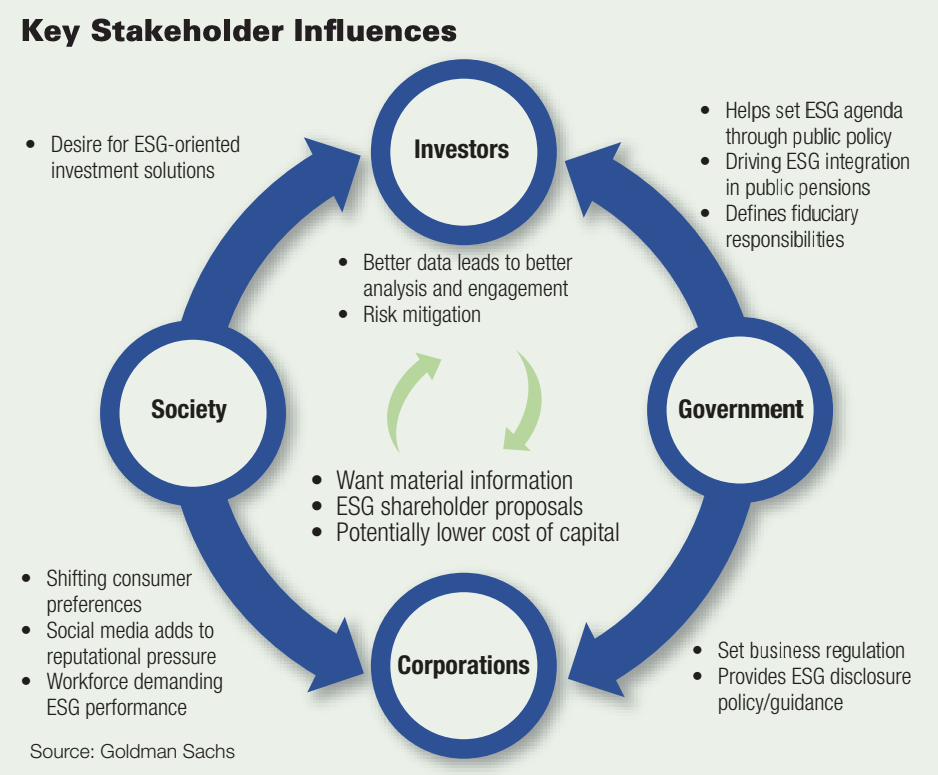

While a combination of factors typically goes into most investment/divestment decisions, the Paris Agreement undoubtedly played a role in investor attitudes on ESG issues.

“There’s no question that in the last decade—particularly in the last three years or more since the Paris Agreement—there has been greater and greater investor awareness of environmental sustainability as an investment strategy,” Molchanov said.

“At the Paris Agreement in December 2015, there was a lot more talk about climate change and carbon emissions.”

However, the simultaneous timing of two trends—the signing of the Paris Agreement and a collapse in crude prices beginning in late 2014—has made it harder to assess the impact of each factor, especially given the string of losses in energy equities during recent years.

Are weak asset inflows into energy aggravated by anti-fossil fuel sentiment or is it simply a case of subpar performance?

“Oil and gas has underperformed the S&P 500 in eight of the last nine years—every year with the exception of 2016,” Molchanov said. “Investors have just been so frustrated by energy stocks that there’s a lot of apathy.

“Eight years of underperformance helps explain why investor appetite for oil and gas equities is a lot lower than it used to be historically.”

A Story Of Mainly Small Caps

While the renewables sector has a number of long-established players, they are not of the scale of many larger oil companies. As of mid-April, Florida-based electric-power behemoth NextEra Energy Inc. had a market cap of about $90 billion. In Europe’s wind sector, Orsted A/S, Vestas Wind Systems A/S and Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy SA had market caps of around $31 billion, $18 billion and $9 billion, respectively.

“There are some large companies in the sector, but investing in renewables and clean tech is still largely a story of small caps,” said Molchanov. “It’s a wide spectrum. Some are profitable; some are not.

“But as the share of low-carbon energy in the global energy mix rises over time—and it’s rising every year—it follows that the relative market cap and relative investability of the companies will also be on the rise.”

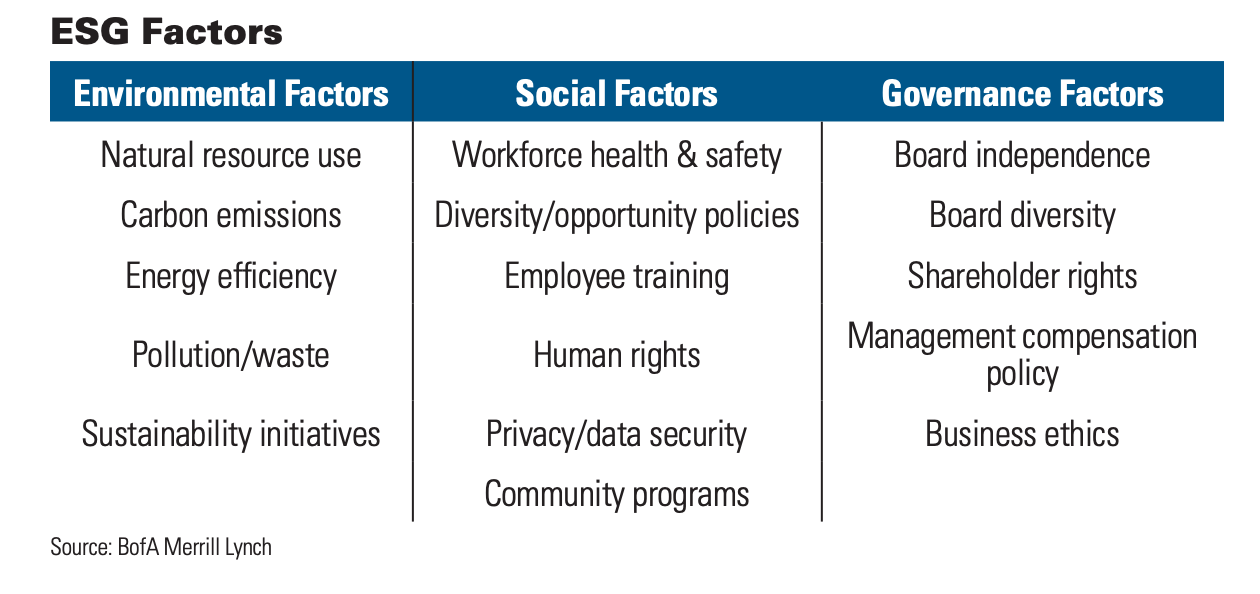

For investors taking a proactive view of energy—and looking for those companies with advantaged ESG practices—the Raymond James analyst suggested screening for producers that actively seek, among other measures, to avoid oil spills; reduce the flaring of gas; and pursue steps to lower carbon emissions and methane leaks.

Climate Change Policies

Robert Plummer, a Scotland-based vice president with research and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, was quick to highlight the faster pace of developments related to ESG issues that has occurred among European investors vs. their U.S. counterparts.

“I think Europe is quite a way ahead of the U.S. in considering these issues and concerns of general investors,” said Plummer. “When I speak to fund managers, they say they’re getting lots of questions from clients, such as university pension funds or other institutions.

“They’re saying, ‘I don’t want you to invest in oil sands,’ or they’re nervous about complying with their policies on climate change.”

Plummer cited a couple of companies that planned to take advantage of current market sentiment to raise “ESG energy funds.” By contrast, “general investors have gone off traditional oil investments massively over the last four or five years,” he said.

Despite recent gains, “the performance in the energy sector has been pretty painful.”

One of the key factors for U.K.-based integrated producers is that “they’ve got very big brands. They employ over 50,000 people. And if you want bright, young people to come and work for you-—and it’s generally the younger generation that is environmentally more sensitive—you have to attract them by saying ‘We’re going to drive the change’” during what WoodMac calls “the transition phase.”

Investments by European integrated producers in the renewables sector account for “less than 10%” of capex budgets each year, Plummer said. In some cases, there is an opportunity cost in pursuing the projects. WoodMac studies show renewable projects often generating sub-10% returns, trailing traditional energy-project returns on an unrisked basis.

“If you’re competing to undertake an offshore-wind project, for example, it’s a very competitive market,” said Plummer. “It’s relatively low risk, and you’re not pushing the boundaries on technology.

“It’s difficult to see how you can generate high returns. And you’re seeing low returns on solar projects. When you have auctions for the licenses, it’s incredibly competitive.”

What is the trade-off that makes the relatively modest returns on renewables attractive? “There’s a general concern of risk,” said Plummer.

investing is to be

an active fund

manager, but not

an ‘activist,’” said

Jeremy Javidi,

lead portfolio

manager of

Columbia Small

Cap Value I

Strategy. “ESG

is a tool in the

toolkit; it’s not a

philosophy.”

“Big investors are nervous about possible legislation on climate change arising over the next 20 years. If you’ve done nothing, you may expect to face someone trying to bring litigation against you.”

Traction In Investor Mindshare

Based in Boston, Jeremy Javidi has a highly opportune position to evaluate issues affecting flows into energy and the potential effect ESG issues may have on the sector. Not only is he the lead portfolio manager of Columbia Small Cap Value I Strategy, he also is the portfolio manager chairman, overseeing all proxy-voting issues related to ESG issues, at Columbia Threadneedle Investments.

Columbia Threadneedle’s most recent tally of AUM is $459 billion. It estimates that it has some $29 billion—about 6% of its assets—in funds with a “responsible investment” (RI) moniker, akin to a “sustainable” designation. The RI funds are growing at about a 15% annual rate in AUM at Columbia Threadneedle, which Javidi says is typical for the fund industry as a whole.

Having spent 17 years working with Small Cap Value I Strategy, Javidi is a generalist with a significant amount of experience in the energy sector. His fund, as of early April, was positioned to benefit from a higher commodity price, and “E&Ps make up the majority of our energy holdings,” he said.

Against the overweight E&P position, the fund was underweight in oilfield services and refining.

SRI (socially responsible investing) funds are a fund category “that is gaining traction in terms of investor mindshare,” Javidi said. “It has been driven mainly by our European clients, as well as some of our U.S. institutional clients and some of our other foreign clients.

“For now, we’re not seeing a lot of traction for ESG investing from U.S. retail clients through mutual funds, although they do increasingly align their investments with their viewpoints,” he added.

“The key to ESG investing is to be an active fund manager, but not an ‘activist.’ ESG is a tool in the toolkit; it’s not a philosophy. If ESG is the only thing you look at, it’s an incomplete picture of how stocks work.

“Over years and years, it’s been shown that the stock market is correlated to the direction of earnings. If earnings are going up, stocks go up.”

ESG funds are, by and large, able to invest in E&Ps, although accessing certain ESG data is a high priority. “A sustainability report showing a policy that considers all the stakeholders in how you operate your business is a very important dataset for all these ESG investors,” Javidi said.

“Just as fundamental investors, like me, are looking to have 10-Ks, 10-Qs and earnings releases, a lot of the ESG investors are looking to have sustainability reports that allow them to conduct their analysis.

“Right now there is a dearth of data out there. Any kind of E&P data that demonstrates superiority from an ESG perspective can actually attract ESG funds. It’s another way of differentiating yourself relative to your peers.

“In a commodity business, like oil and gas, it helps to have data showing fewer accidents on the job site, better environmental track record, more safety controls, etc.”

For smaller E&Ps, with less scale of production, this may represent a challenge, but “the data doesn’t have to be voluminous, like for ExxonMobil or BP [Plc]. It’s not a matter of how much data; it’s about presenting it in a way that helps another subset of investors have a better understanding of the company.

“I don’t want E&Ps that we invest in having to hire a consultant to produce a report.”

Javidi pointed out that relevant data relates to information that is most material from a financial perspective. This narrows down data to that which can help judge the sustainability of an investment from a financial point of view.

The firm’s “ESG Materiality” is based on the research framework that can be obtained from the Sustainability Accounting Standard Board (SASB).

In addition, good governance practices should “start to permeate throughout the oil and gas industry,” Javidi said. “Earlier, when E&Ps were smaller, they tended to invite their friends and family onto their boards.

“What is really important now is board composition, board tenure, making sure that those on the board of directors really are diverse in terms of background and thought.”

Paradigm Shift

Javidi described the transition that the energy sector is undertaking as it moves from a “technology play” to an “industrial play” as a “paradigm shift.” In the industry’s early days, when it was “truly a technology investment,” investors were willing to shoulder losses from a set pool of investments in expectations of a long-term total return, he recalled.

we’ve ever had a

client say that it

was redeeming

from us because

of a fossil fuel

ethic,” said Shawn

Reynolds, portfolio

manager for the

Global Hard Assets

Fund at VanEck

Corp.

With the prior investment pool depleted, a new brand of investors with new metrics has emerged, he said. The new investors are no longer striving for production growth and maximizing net asset value, but, rather, a return on invested capital (ROIC) that is above an E&P’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and, with it, the ability to generate a free-cash-flow yield.

“We’re really excited if the industry continues on that track,” Javidi said. “This year, with the tailwinds of higher oil prices, if we see managements restrain their natural tendency to increase capex budgets, I think the market will view that restraint very favorably—that is, in seeing that the incremental free cash flow is not going to be put right back into the ground.”

As E&Ps progress from single wells to multiwall/pad development, he continued, “now is the time to show their operational efficiency and how much they can drive down the cost of a barrel, so they can maximize their margins and improve their ROIC.

“And as their ROIC exceeds their WACC, that’s the time to make a decision as to re-accelerating growth.”

Javidi characterized the ESG factor as “a sub-plot” in the overall refocusing of the industry to a sustainable business model. And he is optimistic about the outlook for E&Ps.

“What I’ve seen time and time again is that the market is always greedy,” he commented. “As these companies transform their business models, and as they demonstrate that they can earn their cost of capital—even in a very capital-intensive sector like oil and gas—the money will come flowing right back to the sector. People are waiting and looking for those opportunities.

“And those opportunities will accrue to those operators who are more efficient, who can really streamline their operations with multiwell pads, pipelines and infrastructure.

“The new breed of investor wants to see a return on investment: How much did you invest in the ground, and what returns have you generated on that investment? I think the industry is moving in a really strong direction.”

Assessing For ESG

New York-based Van Eck Corp. has a good view of fund flows from a variety of vantage points. Not only does it manage traditional energy investments, but its hard asset fund also has exposure to a number of renewable investments. In addition, Van Eck’s exposure to mining investments gives the firm insights into how ESG issues affect not just energy, but also other primary industries.

As for the impact of anti-fossil fuel sentiment, there is always “headline risk, but we really haven’t seen any overt outflow of funds because of it,” said Shawn Reynolds, portfolio manager for the Global Hard Assets Fund at Van Eck. “I can’t recall we’ve ever had a client say that it was redeeming from us because of a fossil fuel ethic.”

Notably, as with many other professional asset managers, VanEck is a signatory to the Principles for Responsible Investment. “Everybody has to be assessing how their process deals with ESG factors,” said Reynolds.

“If you think about what we do in various major sectors—oil and gas, mining, farming—you have to worry to varying degrees about the potential environmental impact. There’s always been environmental opposition to these projects, and there’s often been risk of damage or disaster.”

In addition, the emphasis on the social issues of ESG has increased significantly, according to Reynolds. “For example, if you go to a copper mine in Zambia, we don’t want to see just the copper mine and the ore-processing operations,” he said.

“We also want to see what the camp looks like, what kind of local communities exist, what level of health and educational facilities are available, what kind of water has been put in place by the company. We take site visits very seriously.”

Similarly, the governance element of ESG characteristics has been increasingly in focus, said Reynolds. “We have a very active engagement on the governance side with almost every company in which we invest,” he stated.

“Big investors are nervous about possible legislation on climate change arising over the next 20 years. If you’ve done nothing, you may expect to face someone trying to bring litigation against you.”

—Robert Plummer,

Wood Mackenzie

“Has engagement ratcheted up over the years? Absolutely, it has. Part of active management is assessing how governance is working at the company, and whether it needs to be improved. Again, that’s inherent to our process.”

Opportunities Lacking

Given the rapid rise in the number of sustainable and SRI/RI funds, the impression might be that some serious dollars are being put to work. Is that the case, especially among active managers?

“We’ve done research on actively managed, environmentally focused funds, and there is very little out there that is investible at the institutional level,” said Reynolds. For a typical pension fund, he said, most potential holdings in the sector would fall short due to being either too small or too volatile; having an ill-defined process and little or no track record; or lacking adequate back-office controls.

From a pure environmental or an ESG perspective, players of substance in the sector appear to be few and far between, according to Reynolds. “In fact, we’ve had a really hard time even defining what that opportunity set is. How big is the universe? It’s not that big. That’s probably why you don’t see a very large, established actively managed fund in the sector up to this point.”

Setting aside Tesla Inc. and a handful of other stocks, “it’s hard to get liquidity and market cap without going way down in scale, which in turn creates structural risk unrelated to the fundamentals of the company you’re investing in,” said Reynolds.

“That poses market risk, liquidity risk. To find 40 to 60 stocks in which you can invest in this space is really, really hard.”

The charter of the VanEck Global Hard Assets Fund calls for investments in not just energy, but a variety of hard assets. For example, the fund has holdings in Ormat Technologies Inc., which owns and operates geothermal energy plants, producing electricity; in Glencore Plc, the world’s largest producer of cobalt, a critical component in batteries; and Sunrun Inc., the largest U.S. residential solar-installation company.

Reynolds cautioned against too heavy an emphasis on a single one of the ESG factors. As an example, he cited the early entrants into solar business—dubbed “evangelicals”—who were driven by environmental issues, but lacked a sustainable business model. By comparison, Sunrun changed the solar model around by initiating the leasing of solar equipment, he said. The stock was up 85% in 2018, he added.

With seemingly a much smaller opportunity set in the renewable sector, what’s the outlook like back on the traditional energy side of the fence?

“Nobody had ever invested in shale before, and we’re just now getting to the harvest stage,” observed Reynolds. “The inflection from investment to harvest is now being reflected in the financial performance.

“E&Ps are talking about generating FCF, there is a dramatic increase in share repurchases and dividends are growing very significantly. The E&P sector is doing the right thing with its return of capital.

renewables

is you have a

lot of people

chasing them,

and you face

very competitive

markets,” said

William Prather

III, head of natural

resources and

infrastructure at

UTIMCO.

“As every quarter goes by, and they continue to be disciplined—and continue to stick with this new strategy of return of capital—they will be rewarded. And the big thing will be that we’ll likely see multiples expand.”

Most Approachable Market

William Prather III is head of natural resources and infrastructure at UTIMCO, which is based in in Austin, Texas, and makes investments on behalf of the University of Texas and Texas A&M University systems. He is in charge of investments made in several main sectors: energy, metals and mining, infrastructure and agriculture.

Private-sector investments are generally benchmarked against Cambridge Natural Resources, an index developed by Cambridge Associates LLC and is weighted close to 90% energy. The predominantly U.S. upstream energy weighting reflects the latter’s “huge” market size and liquidity, with estimates of $500 billion of global capex spent each year and a roughly similar annual opex, according to Prather.

“You’re talking big markets,” Prather commented. Given its size, “it’s the most approachable market. People find it very easy to step into it.”

In terms of tilting investments more towards renewables, Prather pointed to U.S. studies that indicate the U.S. is “a fair bit behind our global counterparts on the percentage of the population that believes in climate change.” As a result, “I would expect European investors to have a much more entrenched view of hydrocarbons and what levels are sustainable.

“I think renewables are an important part of people’s portfolios. The trick with renewables is you have a lot of people chasing them, and you face very competitive markets.

“In the U.S., a levered return on a new renewable-power asset, like wind or solar, is sub-10%. Those are tough returns from a portfolio context if you’re competing with private equity returning mid-teens percent.”

As a result, investors have started to look overseas, with Japan attracting interest, according to Prather. The initial rounds of renewable development were getting fairly attractive power purchase agreements or “feed-in tariffs,” guaranteeing a price for electricity from the government. With these, power plants could be built and generate attractive returns—but returns outside the U.S.—he said.

A Growing Renewables Pie

“The renewables pie is growing, and it will continue to grow. It’s just really competitive,” Prather said. As for talk of the renewables sector being able to completely replace traditional energy investing, “my personal opinion is ‘No.’ When I model it out, I think you still have 10 to 15 years before you even see crude oil demand roll over.”

Looking at the transportation segment of demand, the passenger vehicle market is likely to be the most prone to transitioning away from oil to an alternative energy source, according to Prather. Trucking will find it harder to transition due to the weight of batteries and the distances involved. And, of course, the airlines will be slowest: “Think about the weight,” said Prather.

Outside transportation, the chemicals and plastics sector will tend to be somewhat immune to declines in its demand for oil. “It’s really hard for these companies to transition off hydrocarbons when they’re effectively making new products out of oil,” observed Prather.

In addition, the “funny thing is that people say fossil fuels don’t have a place in the market, but natural gas is a much cleaner fossil fuel. It plays an important role and it will continue to play an important role. Not many people have natural gas consumption really going down in their models.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR:

A Holistic Approach

Alanna Fishman, vice president with Cornerstone Energy Solutions, draws a distinction between current ESG investing and some prior practices that simply excluded investing in specific companies or industry verticals. Cornerstone provides strategic advisory and business consulting services to firms across the energy sector, including developing, managing and communicating ESG and sustainability programs.

Alanna Fishman, vice president with Cornerstone Energy Solutions, draws a distinction between current ESG investing and some prior practices that simply excluded investing in specific companies or industry verticals. Cornerstone provides strategic advisory and business consulting services to firms across the energy sector, including developing, managing and communicating ESG and sustainability programs.

“The attraction of ESG investing—and why people are actively participating in the space—is because it is no longer ‘exclusionary,’ said Fishman. “Investors do not have to exclude whole swaths of investment opportunities, which reduce the potential universe of securities and can impact returns. In oil and gas, ESG provides a holistic vantage point of risk along with financial considerations, such as value and growth. It’s no longer a case of mandating complete divestiture from oil and gas to incorporate ESG.

“It’s widely recognized that we’re not moving away from oil and gas quickly; we’ve built our economy around it,” continued Fishman. “What’s new is that some of the major players in the industry—BP [Plc], Royal Dutch Shell [Plc], ExxonMobil [Corp.], etc.—have realized that there is an inherent value in being a best-in-class actor and by considering ESG factors in their business strategy and risk mitigation plan.”

“Now what’s happening is that investors are saying, ‘We don’t have to choose between doing what is socially responsible and getting returns for our clients. We are able to tilt our portfolios toward companies that are best-in-class actors, so that you can have E&Ps or oilfield service companies in a portfolio. And that brings diversification, which can mitigate market risk. That’s the difference: We’ve gone from exclusionary to tilting and best-in-class integration.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Chris Sheehan can be reached at csheehan@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

E&P Highlights: April 15, 2024

2024-04-15 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including an ultra-deepwater discovery and new contract awards.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Offshore Europe, Middle East

2024-04-16 - Part three of Hart Energy’s 2024 Deepwater Roundup takes a look at Europe and the Middle East. Aphrodite, Cyprus’ first offshore project looks to come online in 2027 and Phase 2 of TPAO-operated Sakarya Field looks to come onstream the following year.

E&P Highlights: March 15, 2024

2024-03-15 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a new discovery and offshore contract awards.

E&P Highlights: March 25, 2024

2024-03-25 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a FEED planned for Venus and new contract awards.

Remotely Controlled Well Completion Carried Out at SNEPCo’s Bonga Field

2024-02-27 - Optime Subsea, which supplied the operation’s remotely operated controls system, says its technology reduces equipment from transportation lists and reduces operation time.