Illustration by Robert D. Avila

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the September 2020 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Get ready. The RBL redetermination season that comes around every fall is fast approaching, but it could be more fraught than usual this year. Many E&P companies find themselves painted into a corner: They are fully drawn, or worse, overdrawn, on their revolving credit lines—just when the value of their reserves (collateral) has declined. Worse, their traditional bankers may not be apt to help, as many have pulled back from the space.

“The COVID-19 pandemic only accelerated what was already a challenged market in 2020. I think a lot of the ‘fringy-ier’ banks are getting out of energy, but just about everyone is trying to reduce their exposure,” said one alternative debt provider. “Some banks find that the risks turned out to be bigger than they thought, and they are trying to consolidate or wind down their portfolio, and some are saying, ‘Get me out of energy; I don’t care what it takes.’”

What does it take? The natural buyer of a loan would be another bank or an investor with a higher hurdle rate and a long-term view. In any case, big discounts would be needed to attract a buyer.

“Even a healthy credit has to be priced attractively,” said Phil Pace, senior advisor on the investment committee for Chambers Energy Capital, a debt provider that is an alternative to commercial banks. The high yield or term loan markets are also in relative disarray and will be more expensive than a reserve-based loan (RBL)—and more expensive than they used to be, he added.

Chambers provides debt structured as first and second-lien credit, or unsecured debt, net profits interests and mezzanine transactions for small and medium-sized E&Ps.

Risk appetite has gone on a strict diet. Capital sources who were satisfied to be in subordinated debt positions before this crisis now prefer to be at the top of the capital stack or have “first-dollar-risk,” said David Morris, managing director of Opportune LLP’s restructuring practice in Dallas.

Debt analysis and debt repair has set in across the industry, probably taking up more executive time than figuring out how to solve problems between parent and child wells. The task is enormous. Recently JP Morgan Chase said U.S. banks hold some $650 billion in energy-related loans (only 3.5% of their total book, but still, significant).

Davidson Hall, head of the debt capital markets group at Stephens Inc., noted that while banks can be accommodating to some clients at a high level during the pandemic-induced economic slowdown, energy loans are another matter. “My guess is, banks feel they can be more aggressive with an energy company because some of these companies weren’t doing all that well before the pandemic anyway.

“This gives the banks some ‘air cover’ to be politically correct while they clean up their own balance sheet. Otherwise, if big-balance sheet banks are splashed across the media that they pushed a third-generation family energy company [into bankruptcy] that would not sit well with anyone on Capitol Hill.”

Plan now

What should an E&P company do? It is never too soon to start planning for contingencies and thinking about alternative sources to replace or supplement bank debt, advises Jonathan Harms, director, senior debt, for Opportune. “If your RBL is changed and that just put you into a liquidity crunch, you can still pursue alternative capital sources, but it will likely be more expensive, and it might be too late.

“Starting early is the most prudent thing to do.”

It’s very important to be thinking ahead, agreed his colleague, Morris.

“One thing we’ve seen companies do is look for second lien financing, or a structure where junior debt is somewhere between the borrower’s credit line and secured with a second lien on the collateral.

“But even junior debt shops are being much more disciplined these days. The days of taking an approach that they are agnostic as to oil or gas, or to play or location, are over,” said Morris.

Rise of debt alternatives

Alternative lenders see increased opportunity in the current disarray. One grabbed headlines in July: Oaktree Capital Management LP., the largest distressed securities and credit investor in the world ($125 billion under management), acquired Hancock Whitney Corp.’s $497 million of energy loans, enabling the bank to clear its books of energy.

Oaktree acquired the bank’s reserve-based loans (RBL), midstream and nondrilling service credits, for $257.5 million—roughly 50 cents on the dollar. A special provision for credit losses related to the deal of approximately $160.1 million (pre-tax) was included in the bank’s second-quarter results.

“The primary objective of this sale is to continue de-risking our loan portfolio by accelerating the disposition of assets that have been impacted by ongoing issues within the energy industry, and have now been further complicated by COVID-19,” said John M. Hairston, the bank’s president and CEO, in a statement.

Another indicator of how much the financing environment has changed: A recent survey of E&P companies by Haynes & Boone law firm indicated that they expect to get 28% of their capital from cash flow and 20% from debt alternatives. Tellingly, bank debt was ranked third, at only 17%.

An example (although not in the energy space) shared by Stephens’ managing director Keith Behrens emphasizes how much debt markets have changed: “It’s really important to bring new sources to the energy market, because you can’t go to the 10 guys you used to and get five term sheets anymore.

“We went to 210 capital providers for one deal and received only 20 term sheets, and ultimately, we let 10 into the next round. As soon as we did that, two of the 10 immediately passed. They want to look like they are in business when actually, they are not. In a normal environment, I wouldn’t have gone to 210 providers; I’d probably have gone to 30.”

In unitranche deals, historically, providers advanced 80% to 100% of the PV-10 reserve value, but that’s come down today to maybe 60% against PDP value, Behrens said. Credit for backing acquisitions is tough: While an E&P might be able to buy assets cheaply, unitranche lenders have also come down in the amount of PDP they’ll loan against, he said.

A borrower looking for capital these days faces so much uncertainty. Companies find they can’t necessarily rely on their existing bank relationships—but getting capital from a new lender is limited too.

“We got a call from an operator with no debt and a PDP reserve base with attractive upside, but he could not get a call back from any bank,” said Justin Moers, of Munich Re Reserve Risk Financing Inc. “That really tells you the market is closed.” Munich Re provides debt capital in a range of $75- to $250 million.

As one banker told Investor, “I have to reserve my capital to help my existing portfolio of energy companies. It’s better to do a deal with the devil you know than the devil you don’t.”

Hedge fund investors that now want to invest in energy debt will charge a higher interest rate than traditional bank lenders, but “Once you put it to bed, it goes to bed and doesn’t have to get reviewed twice a year,” noted Ann Rhoads, a career energy banker who now advises Odinbrook Global Advisors, which advises companies in need of restructuring that may be too small for the likes of some of the bigger restructuring advisory names such as Lazard Partners, Alix Partners or Alvarez & Marsal. Odinbrook was formed in 2014 by Steven Strom, formerly a top restructuring advisor with Jefferies, Blackhill Partners and other firms.

“I do think some of these competitive alternative investment funds are probably more conservative than they were two years ago. Nobody is going to do more than they have to do right now,” she said.

Chasing illiquidity

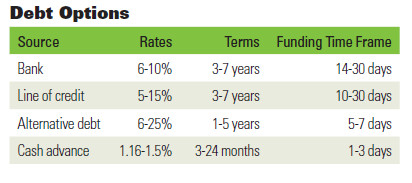

The various alternative debt structures available typically fall between a traditional RBL from a bank and private equity or a mezzanine deal. They feature customized terms and often can be closed faster than a bank agreement. Like banks, they require a meaningful amount of flowing PDP (proved developed reserves that throw off cash flow), but “nonbank banks” can stretch more, assigning a bit more value.

A senior unitranche structure seems to be a preferred replacement for an RBL. It separates the collateral from the estate of the borrower, and it puts the lender in a senior first-lien position. The coupon is higher than for an RBL.

A senior unitranche structure seems to be a preferred replacement for an RBL. It separates the collateral from the estate of the borrower, and it puts the lender in a senior first-lien position. The coupon is higher than for an RBL.

Despite various structures or options that are available, underwriting is now difficult because no one really knows when the energy business will return to normal, or what normal will look like.

“While times look tough right now and the industry is constrained, there is capital available, but the terms will not look like they did during the heyday of the shales,” said Moers.

The run for the exits is creating a need for new capital sources, and fortunately, many of the alternative debt providers see growing opportunities to invest in oil and gas today, as market dynamics have been pushed and pulled by oil price volatility and demand uncertainty. They might buy bank debt, stock options or royalties; provide a volumetric production payment (VPP), or provide debtor-in-possession financing during a bankruptcy workout; or exit financing after a company exits bankruptcy. In a larger bankruptcy filing especially, there are a lot of moving pieces and distortions of value that create new opportunities to buy or sell.

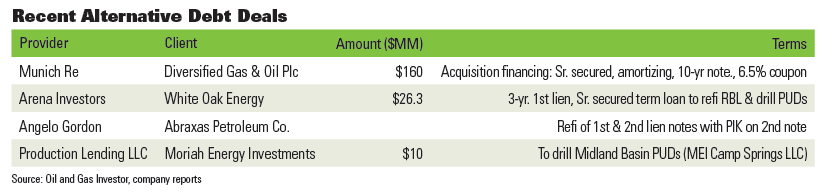

“As banks move up their reserve levels, you’ll see more banks exit this area,” said Dan Zwirn, CEO of Arena Investors LP, a credit-focused investing group with about $1.5 billion under management. The company calls itself “a chaser of global illiquidity.” It has acted as lead investor and structuring agent on nearly 20 deals in the last four years to June 30. It employs first and second-lien structures on producing assets, and provides VPPs, minerals financing and joint venture equity.

For Arena, investing in oil and gas is a great opportunity, just as long as hedging by the E&P borrower is part of the deal. It acts as a facilitator for companies that have the ability to move their PUD inventory to the PDP column (undeveloped reserves to proved, producing), and a borrowing base that is no more than 10% allocated to PUDs, Zwirn said.

Typical deal size ranges from $10 million to $50 million. Arena has also provided debtor-in-possession financing so that companies in bankruptcy, or even just prior to filing, have enough capital to keep employees operating the assets. “If a bank says, ‘We’re just not underwriting another nickel,’ the E&P still needs capital. These assets don’t get up out of the ground by themselves. So, we’re kind of a ‘Swiss Army knife’ of solutions,” Zwirn told Investor.

Now that the so-called shale gale is past and the accompanying financing frenzy has calmed down, the people with capital and the people who need it are reflecting on what went wrong, what went right, and the way forward.

“I’d argue that when everything is rosy, banks tend to over-advance [on reserve values] and when commodity prices drop they tend to under-advance, and with draconian terms,” Zwirn said. “So, I think banks tend to do the wrong thing in each direction.”

Arena’s principals have entered, left and re-entered the energy space when and if the numbers dictated. In the 1990s when oil plunged below $20/bbl, Arena started investing, and in the early 2000s, it began looking again at buying energy loans from firms like Shell Capital, Duke Energy and Enron as the latter “nonbanks” exited.

At one time, Zwirn helped create and finance Petrobridge Investment Management LLC to provide debt capital, but by the late 2000s, commercial banks were returning to the energy space in a more aggressive way than ever before, as everyone rushed to join the shale revolution. By then, deal terms were becoming too frothy, and the numbers no longer worked, Zwirn said.

Indeed, repairing capital dislocation is an all-consuming chore. “There was way too much leverage in the shale boom,” Zwirn said. “The leveraged finance world went to lending on P1 and P2, and it created a false sense of security. People were not making the distinction between PDP and PDNP reserves.”

Today, “an E&P private-equity apocalypse” has set in (as Zwirn told Institution Investor magazine in April), and public financing and banks are redlining the industry. “These factors add up to a pretty interesting investment opportunity. There’s a lot to be done out there… to step in and finance solid operators who have a view on prices or an ability to move reserves up to PDP,” he said.

A case study

Zwirn cited a recent deal without naming names. A conventional bank group had financed a well-known, private-equity-backed company that was pursuing conventional assets. The bank line was $250 million. But then recently, the banks had to write off nearly 90% of that loan (although one member of the bank syndicate thought that there was still something worthwhile there, in spite of the write-down).

The remaining syndicate member rolled that debt into new equity, and Arena advanced 60 cents on the PV-10 dollar of the proved developed producing reserves, and it also took some penny warrants. In addition, Arena required the borrower to contract with a well-known hedger to buy forward for three years a portion of the E&P’s production.

“We’ve focused on conventional, vertical production, with long-lived reserves that are operated. We might do a shale deal, but it will cost you,” Zwirn said. Of about 25 transactions we’ve done in the last three years, we’ve been involved in only one shale deal.”

Actively seeking deals

Cibolo Energy Partners LLC is actively seeking to deploy debt capital from its latest $260-million fund, which dates from 2018, and from which about half the capital remains, according to J.W. Sikora, managing partner and co-founder. With co-investments and 22 limited partners, some $400 million was raised altogether, so the Houston company now has about $150 million in dry powder left.

The company prefers first-lien, senior secured, unitranche deals in the range of $20- to $80 million, with $20- to $30 million being the sweet spot.

These are backed-stopped by producing assets and conventional opportunities. It prefers to be the sole lender in each case, so there is no bank debt ahead of Cibolo and no second-lien debt behind it.

“For new deals, we haven’t deployed any new capital, but we’ve deployed capital into our existing companies. On new deals, it’s been a whole lotta lookin’,” Sikora said. “We’d like to add one or two more companies this year and two or three next year.”

Cibolo has five portfolio companies at present, and they are hedged. During the downturn some of their production was shut in, and none of their rigs has been stood up yet. In another sign of caution, the lender’s covenant terms say that, in most cases, there are limits on how much vendor debt a borrower is allowed to have.

Like other sources we spoke to, Sikora wonders how and when private-equity players will re-emerge from their lockdowns to either buy assets or advance capital to E&Ps. Meanwhile, Cibolo and its existing portfolio companies are not focused on growth.

“I say, let’s keep production flat, let’s build liquidity, where can we ‘manufacture’ cash by reducing costs? Let’s find rock we like, and then wait until we can get a 25% return. You don’t want to stick a drill bit in the ground at $40 oil.”

Other deals

In May Munich Re closed its second acquisition financing for Diversified Gas & Oil Plc, an active Appalachian consolidator. The first deal was done in November, but this time, everything was done remotely for the second term loan Munich Re has provided to the company. In aggregate it now has $360 million invested in DGO.

This was a 10-year amortizing, senior secured loan backed by working interests, with a 6.5% coupon. Those interests were placed in a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that was nonrecourse to the company. “The SPV becomes the borrower,” explained Chad Mabry, vice president, Munich Re, and “This is a fixed coupon that doesn’t float with LIBOR or other metrics.”

Munich Re provides first-lien debt and some second lien, but only if the credit metrics are consistent with a first-lien borrowing transaction. Capital can be for an acquisition, general corporate purposes or a recap. Preferred deal size is $75 million to $250 million.

“We’re seeing a lot of things that need some kind of restructuring or recapitalization, but the equity value is so depleted that there’s not much we can do, because the oil price decline has affected reserve values,” said Moers. “We still promote the same structures, but the universe of assets or opportunities that were of scale no longer have the same scale—and, the G&A drag is increasingly a problem.”

E&P companies have to decide if they want to step into a term loan with a provider like Munich Re, with a term of five to seven, even 10 years, that comes with a higher coupon, or, stick with an RBL that has more restrictive covenants and has to be reviewed twice a year, said his partner, Mabry. In either case, interest rates are likely higher now than they were last year.

CSG Investments Inc. also lends in a structure between the RBL and private equity, in customized, senior secured loan and mezzanine debt. It provided a $65 million term loan to BJ Services and $100 million to Keane Group Holdings, for example. It participated in the $4 billion bridge loan made to Chesapeake Energy Corp. prior to its bankruptcy filing and in the $750 million loan to Chaparral Energy Inc. as well. It did so by buying certain amounts from the underwriters of these deals.

In the end, companies that face a large decrease in their RBL this fall have a good sense of that already, and what’s more, they are already on the radar screens of the alternative debt providers, according to Jonathan Harms with Opportune. If they are overdrawn past their PDP or PV-10 value, that spells trouble in this environment. The time to act is now.

Recommended Reading

Midstream Operators See Strong NGL Performance in Q4

2024-02-20 - Export demand drives a record fourth quarter as companies including Enterprise Products Partners, MPLX and Williams look to expand in the NGL market.

Post $7.1B Crestwood Deal, Energy Transfer ‘Ready to Roll’ on M&A—CEO

2024-02-15 - Energy Transfer co-CEO Tom Long said the company is continuing to evaluate deal opportunities following the acquisitions of Lotus and Crestwood Equity Partners in 2023.

Apollo Buys Out New Fortress Energy’s 20% Stake in LNG Firm Energos

2024-02-15 - New Fortress Energy will sell its 20% stake in Energos Infrastructure, created by the company and Apollo, but maintain charters with LNG vessels.

Phillips 66 Explores Sale of Pipeline Stake Worth Over $1B, Sources Say

2024-03-26 - The Rockies Express Pipeline is a 2730-km interstate natural gas pipeline stretching from Wyoming and Colorado in the West to Ohio.

Summit Midstream Sells Utica Interests to MPLX for $625MM

2024-03-22 - Summit Midstream is selling Utica assets to MPLX, which include a natural gas and condensate pipeline network and storage.