(Source: Shutterstock.com)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the January 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

When asked about the composition of energy boards and the challenges they will face in 2020 and beyond, I consulted with Allen Brooks, David Heikkinen, Maynard Holt, Ray Singletary, Art Smith, Jim Wicklund and a couple of my fellow National Association of Corporate Directors members. I call them the Brain Trust (BT). Their comments revealed a central theme—make sure you have the right board composition for today and tomorrow. It must be a board that understands the evolving energy market and your shareholder base, has the vision and creativity to make the right decisions for the future and is willing to champion and embrace change.

There are numerous writings on the shale revolution; greenhouse gases; alternative energy; environment, social and governance (ESG); and how the energy industry is changing—even dying. Correspondingly, there is a myriad of papers depicting the right board composition. Although these are very thoughtful, there is no one size fits all. Each board has to ensure it has a vision and strategy to create and grow shareholder value for today.

Let’s revisit a few fundamentals and develop key concepts for a great corporation run by a great board. Every public business has three primary constituencies: (1) employees who provide the goods and services that generate revenues and profits; (2) customers who are identified, studied, dissected and buy the goods and services; and (3) shareholders/investors who provide the needed capital.

Let’s revisit a few fundamentals and develop key concepts for a great corporation run by a great board. Every public business has three primary constituencies: (1) employees who provide the goods and services that generate revenues and profits; (2) customers who are identified, studied, dissected and buy the goods and services; and (3) shareholders/investors who provide the needed capital.

It is this latter group that, unless an activist is involved, gets the least attention and is the least understood. Granted, public companies know their top 10 to 50 largest shareholders. They visit them. They hold analyst days for them. But do they truly know who they are today and what is driving them?

What investors see

The BT pointed out that the investor base has changed. The traditional growth investor who religiously followed energy is all but gone. He has heard two perspectives. On the one hand, energy has said we are in a shale revolution and have become a stable and steady industry, much like farming and manufacturing. On the other hand, he has heard about energy’s demise with the advent of electric vehicles, renewables and the issues surrounding climate change, and has left energy for the FAANG stocks.

Thus, value investors have become the energy industry’s primary source of capital, but they are having trouble buying into it. They see high-spending, over-levered companies when they are really searching for a return of capital, which is available in other industries. As evidenced at EnerCom’s The Oil & Gas Conference and others, most of the energy industry has heard this and is creating dividend and buy-back programs and focusing on free cash flow. The energy industry is listening to the new investors and is headed in their direction, but they are not there yet.

What is the best way to approach the competency/ compensation dilemma? Take the board through a rigorous exercise that delineates which competencies the board should possess in total.

So, what is needed to give the value investor the confidence to get capital flowing back into the industry? As the BT pointed out, debt is not bad if you are earning more than your cost of capital and returning the excess to shareholders.

The BT is adamant that having the right board is essential to achieving this goal. In our discussion, seven key points were highlighted:

- Boards must promote a strategy for the long term. This is self-evident, but the BT believes that boards must constantly be revisiting and challenging the company’s strategy as well as management. If they don’t, an activist will.

- Boards need diversity of thought and experience, especially with the cyclical nature of the energy business. They need to look at a lot of different things at the same time. An entrepreneurial expert who has a different perspective is a great addition to the board.

- Boards need to promote and embrace innovation and creativity. This brought us the shale revolution, and it will take us into the future. Each board should ask how much technology expertise is needed on the board. They might consider bringing someone from outside the industry who has been with an innovative manufacturing company or in the semiconductor industry and looks at technology differently.

- Boards need to make sure they have the right metrics. The BT said that we are not only competing for capital against every other energy company, but also against all global companies. Someone is needed on the board who will bring that perspective and make sure that the company’s metrics are right and provide a return above the cost of capital. Additionally, the BT believes that metrics should be built into compensation programs and seriously questioned whether a board should pay bonuses if the cost of capital is not achieved.

- Depending on the size of the company, the board needs to look at its committee structure and create those beyond the mandated three that will add value—i.e., a finance committee, M&A committee and/or innovation committee. Boards need to be properly structured to help guide and be a partner/mentor to management.

- Consider the value of having one, two or three former CEOs on the board. They know what it’s like to be in the corner office, to be alone and make the tough decisions. They can be a sounding board for a CEO and help think things through.

- Most of all, boards need to consider their composition and competencies. Some need to avoid the danger of a “group think.” Many of these, even diverse ones, are comprised of energy experts/icons who have had successful careers but still think and operate the way the industry has always done things.

On the other hand, some lack sufficient technical expertise, and both miss opportunities and don’t properly allocate capital. The answer? Boards need to take a step back and think about today’s shareholder base and what they are looking for. This is not only in the area of capital but also with new issues such as ESG and cybersecurity. Make sure there are competencies on the board in these areas.

Make sure you have the right board composition for today and tomorrow. It must be a board that understands the evolving energy market and your shareholder base, has the vision and creativity to make the right decisions for the future and is willing to champion and embrace change.

So, what might a starting framework look like at a small- to mid-cap oil company? Obviously, public boards need the three basic committees. If you start with the audit committee, the chairman should be someone from the industry; but at least one, if not two of the other independent members should be from outside the industry and have experience with the value investor.

Governance committees also need a blend of individuals from inside and outside the industry to help avoid the group think. The compensation committee can look the same, but it must be ready to challenge the metrics. If there is a technical committee, the members should have the specific competence needed. If there is no technical committee, there should be at least two technical experts on the board to support.

Overall, a balance of at least 40% of the board members should have operational experience and 40% should have finance and investment experience. The other 20% should be selected to fit the strategy of the company and the makeup of management.

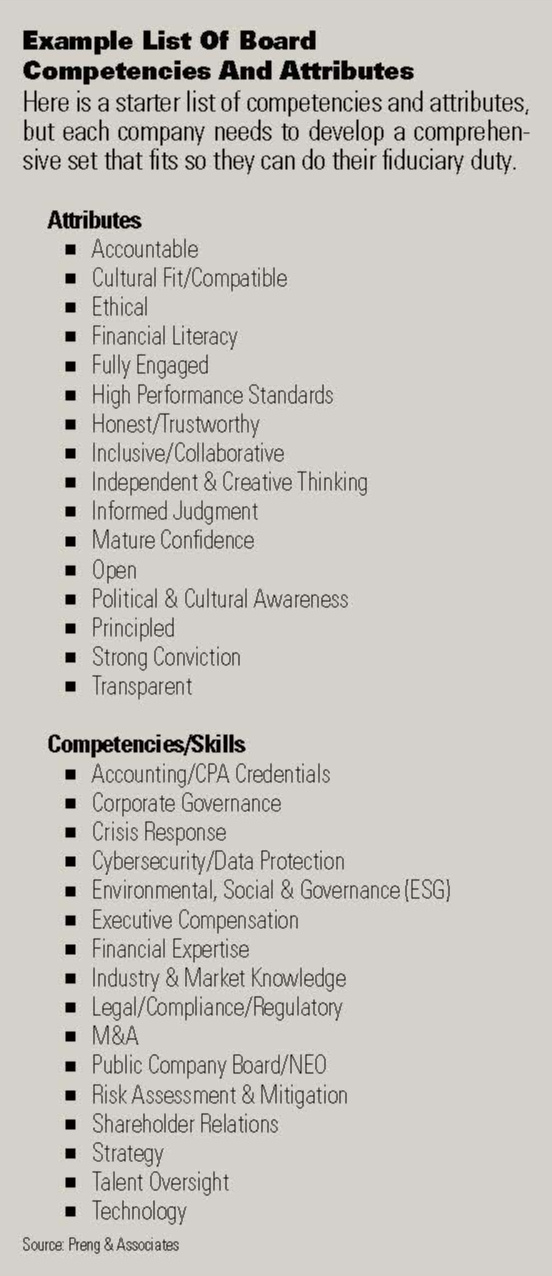

So, what is the best way to approach the competency/compensation dilemma? One solution is to take the board through a rigorous exercise that delineates which competencies the board should possess in total. This process will also compare the current board’s composition/skills against what they should possess.

Outlined here is what our firm has done for some of our clients:

- Create a “competency committee” comprised of the chairman, CEO (if they are one and the same, then the lead director) and non-gov chair to develop the full list of competencies the board must have and create a matrix to evaluate each director’s specific skills.

- Ask the committee members to think, not as directors, but as investors (because they are) and have a brainstorming session to develop the initial competencies list. This session may take two to three hours but, at its conclusion, the committee will have a list of 15 or more competencies that, collectively, will protect and grow a shareholder’s investment.

- Send this initial list to the whole board asking these two questions: “Has the committee missed something that should be included?” and, “Is there something on the list which does not need to be there?”

- Once the responses are collected and revised, the list is sent to all directors asking them to rate the competencies two ways—one is based on the company as it is today and the other assumes that the company will double in four or five years. In essence, challenge the board to think what would be needed at that time. The rating uses a scale of 1 to 5 (from “nice to have” to “absolutely critical”).

- Once this feedback is captured, a final list of competencies is put on a grid (competencies in the left-hand column and directors at the top).

- The next step is for the team to meet each director and professionally interview and evaluate his/her skills/competencies.

- Once done, complete the grid below that shows all the competencies and present the results to the committee. The final product is a document that not only shows any board weaknesses, but also becomes a working guide for the non-gov committee as they consider the future.

I hope the thoughts of the Brain Trust and the grid creation exercise will encourage you to think about your board’s composition.

David E. Preng founded Preng & Associates in 1980 and is president and CEO. Previously, he spent six years in the executive search industry with two international and one national search firm. He has worked on over 2,000 energy-related searches throughout the world ranging from board and senior executive to managerial and senior technical positions.

Recommended Reading

Texas LNG Export Plant Signs Additional Offtake Deal With EQT

2024-04-23 - Glenfarne Group LLC's proposed Texas LNG export plant in Brownsville has signed an additional tolling agreement with EQT Corp. to provide natural gas liquefaction services of an additional 1.5 mtpa over 20 years.

US Refiners to Face Tighter Heavy Spreads this Summer TPH

2024-04-22 - Tudor, Pickering, Holt and Co. (TPH) expects fairly tight heavy crude discounts in the U.S. this summer and beyond owing to lower imports of Canadian, Mexican and Venezuelan crudes.

What's Affecting Oil Prices This Week? (April 22, 2024)

2024-04-22 - Stratas Advisors predict that despite geopolitical tensions, the oil supply will not be disrupted, even with the U.S. House of Representatives inserting sanctions on Iran’s oil exports.

Association: Monthly Texas Upstream Jobs Show Most Growth in Decade

2024-04-22 - Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the oil and gas industry has added 39,500 upstream jobs in Texas, with take home pay averaging $124,000 in 2023.

Shipping Industry Urges UN to Protect Vessels After Iran Seizure

2024-04-19 - Merchant ships and seafarers are increasingly in peril at sea as attacks escalate in the Middle East.