The Permian Basin remains the top oil-producing region in the U.S., producing about half of the more than 8 million barrels per day produced in the country’s top basins. (Source: G.B. Hart/Shutterstock.com)

FORT WORTH, Texas—Operators and service companies in the Permian Basin are tackling the relationship between parent and child wells, tweaking stage spacing and proppant loading and making other adjustments as they continue to optimize and move into full field development.

But players are not using a one-size-fits-all approach in the biggest oil field in the U.S. Many operators are utilizing technologies offered by service companies to improve well performance, while also incorporating their own talents and knowledge gained from peers and past experience. They are doing so with eyes on improving EUR and adding value, without sacrificing the former early on in a well’s life.

A panel of operators and oilfield service providers took to the stage April 17 at Hart Energy’s DUG Permian Basin Conference & Exhibition to talk about completions and best practices surfacing in one of the world’s most-watched basins.

“We have seen a lot of advancements that have been happening in the industry from a service efficiency standpoint and technology, which are allowing us to increase the number of stages that we can frack in a day,” said Faraaz Adil, a Permian Basin-focused technical manager for Halliburton Co. “Operators are … reducing their cluster spacing, increasing the number of stages. They are trying to access as much of the reservoir as they can, and we are seeing advancements where we are using [technologies] like fiber microseismic to analyze the geomechanics.”

Completion efficiency is also coming in the areas of lateral length, clusters and proppant loading, according to Rocky Seal, national product line sales leader of completions and wellbore interventions for Baker Hughes Inc., a GE company. He pointed out how there’s been a lot of experimentation in the last four or five years in these areas, but lateral lengths have flattened out—averaging around 9,000 ft—in the last 1 ½ years.

There are some exceptions to the norm.

Surge Energy, for instance, recently said its Medusa Unit C 28-09 3AH drilled a 17,935-ft (3.4-mile) lateral in the Wolfcamp A. At nearly three times the length of The Hollywood Walk of Fame, the company claims the well has the longest known lateral in the Permian Basin. The well will be completed and brought online later this year, the company said in a news release.

The Permian Basin remains the top oil-producing region in the U.S., producing about half of the more than 8 million barrels per day produced in the country’s top basins. But as oil price volatility continues causing some independents to cut spending while larger companies ramp up drilling plans, thoughts remain on making wells better.

Like its peers, Lario Oil & Gas Co., a private independent that’s been around for about 90 years, has taken aim at stage counts. The average stage count per day for Lario has gone from about five to between eight and 10 when “zippering,” or using a zipper fracks. “The pump-downs is what changes how many stages per day you get because of how long those are,” said Christian Veillette, the company’s vice president of operations.

“We’re constantly trying to improve and optimize all of our processes—whether it’s from sand delivery, fluid delivery. Everything is planned out in such a way that it’s just a well-orchestrated show,” he added.

Finding the incremental economic benefit is a task WhiteHorse Energy LLC aims to accomplish, according to its CEO, Hunt Pettit.

“Everything that was previously mentioned from stage spacing, cluster spacing, higher pumping jobs, the amount of proppant, the amount of fluid: it’s a dynamic balancing act,” said Pettit. “You’re looking at the geology; you’re looking at the geophysics; you’re talking to your vendors; you’re trying to talk with other operators to see what the best practices are. And then you take them back to your own asset and begin to implement them.”

WhiteHorse has been using, for example, diverters at the tail end of its jobs in hopes of making contact and keeping fractures open. “So far, we’ve seen excellent results,” Pettit said.

But Veillette pointed out the difficulty of diverting 10 clusters in the absence of short spacing.

“I see why people talk about it [using diverters] for parent wells, but people never talk about it for the child well,” he said. “My point of contention is you could have tracers and tell me where you put fracs, but you truly don’t know how far they went and which clusters took the fluid. So, you may have some longer fracs where you’ve pumped the diverter because you’ve sealed off some.”

Veillette noted he is more of a fan of old-fashioned mechanical diversion.

“I feel like you need diverter for the exact opposite reason for your child well when you come back,” he said. “You want to seal off where those fracs may have already impacted where the wellbore is being landed for the sibling well.”

However, more companies are using diverters. Faraaz puts the percentage at more than 60%-70%. But how diverters have been used over time has changed, he added. Instead of just dropping a certain volume and hoping for the best, companies are taking a more calculated approach in terms of volumes and learning of the possible benefits beforehand.

It also, perhaps, helps to have downhole cameras.

As operators move into full-field development and manufacturing mode, ensuring that perf clusters work is of concern. Panel moderator Richard Mason, chief technical director for Hart Energy, noted that he’s heard that maybe only 70% of the stages’ perf clusters work. “I would think that any factory that has a 30% error rate is not going to be in business for a very long period of time. What are you seeing in terms of progress in trying to overcome these significant legacy issues?” he asked panelists.

With much conversation around cube development, Faraaz acknowledged well spacing could become a big challenge. Monitoring offset well pressures and examining bottomhole data to gauge cluster efficiency are among the techniques used to help determine cluster efficiency, he said.

“Everybody wants to stimulate as much oil volume as we can,” he said. “To assist that we might have to do different things, so we’re coming up with changes in the way diversion is done.” This includes incorporating automation and looking at pressure fluctuations before changes are made to improve cluster efficiencies.

Talk of choke management also surfaced during the discussion as some weigh net present values (NPV) and EURs.

“We’d rather see 90-day [cumulative]. It’s not just about the 24 hours any more for us,” said Veillette. “Depending on the formation, some have more clay. Some are more prone to be more ductile. So it behooves you not to be more aggressive on choke size.”

As WhiteHorse looks at choke management, it also examines reservoir pressure, Hunt said, adding the company favors early choke management and bringing wells on slowly.

“We’re much more concerned with 90- to 120-day [cumulative] and production rates than we are with a big sexy number,” Hunt said. “On the NPV vs. EUR, if you’re willing to be just slightly patient in the grand scheme of things you can end up with a better NPV and you’re going to get the EUR as well instead of just opening it up potentially causing a lot of problems and hoping you get that sexy number.”

Veillette shared similar sentiments.

“It’s all about economics, but we’re not willing to sacrifice well performance to get NPV on an immediate basis,” he said. “We want repeatability in all of our wells. We’re not here to say, ‘here’s a flashy well.’ We want all of our wells to be consistent.”

Velda Addison can be reached at vaddison@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

Haynesville’s Harsh Drilling Conditions Forge Tougher Tech

2024-04-10 - The Haynesville Shale’s high temperatures and tough rock have caused drillers to evolve, advancing technology that benefits the rest of the industry, experts said.

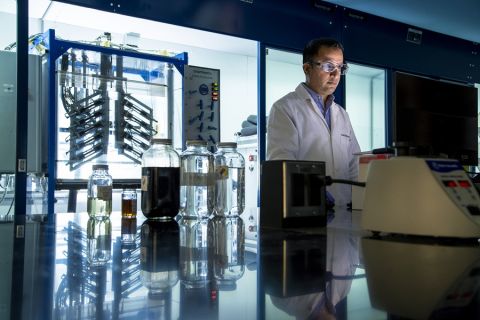

Defeating the ‘Four Horseman’ of Flow Assurance

2024-04-18 - Service companies combine processes and techniques to mitigate the impact of paraffin, asphaltenes, hydrates and scale on production — and keep the cash flowing.

Geothermal ‘Could Save the World,’ but Faces Familiar Subsurface Risks

2024-03-20 - CERAWeek panelists discussed hurdles to widespread use of Earth’s heat to generate power — problems familiar to oil and gas operators.

Exclusive: Halliburton’s Frac Automation Roadmap

2024-03-06 - In this Hart Energy Exclusive, Halliburton’s William Ruhle describes the challenges and future of automating frac jobs.

2023-2025 Subsea Tieback Round-Up

2024-02-06 - Here's a look at subsea tieback projects across the globe. The first in a two-part series, this report highlights some of the subsea tiebacks scheduled to be online by 2025.