The Federal Aviation Administration’s long-awaited “final” unmanned aircraft system (UAS) rule, Part 107, that regulates drones is scheduled to take effect in late August. At that time, current Section 333 holders will be able to choose to fly under their Section 333 exemption or use the new Part 107 rules.

Most commercial operations will choose the latter. Like the Section 333 exemptions, Part 107 allows operators to fly drones in the national airspace for commercial purposes.

We at Aerial Services Inc. were excited in 2015 after receiving a Section 333 exemption. At last! We could use this new technology to expand our remote sensing and mapping operations. We were primed for starting a new, profitable business doing amazing things flying drones. On the surface, the approval to fly “commercially” sounded great.

Restrictive rules

But after a look under the hood we were no longer praising the new rule, and our ebullience quickly faded as we uncovered the true nature of the tough regulations. It turns out the Section 333 exemption and now the Part 107 final rule allow commercial operations—but just barely.

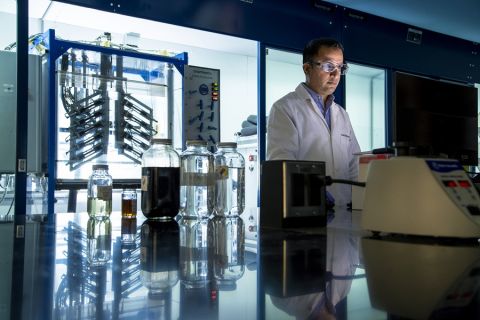

Like other remote sensing and mapping firms, Aerial Services provides professional services to government and civil entities throughout North America in markets like transportation, oil and gas pipelines, forestry, mining and power distribution. Typically, the remote sensing is accomplished using manned aircraft and sophisticated sensors like laser-based LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), digital cameras, radar and gravimeters.

Our manned aircraft systems have great reach. They fly fast. They have large fuel tanks. We can land at any airport, refuel and keep flying. We can fly virtually anywhere at any time with few restrictions. Therefore, the number and types of applications for which these systems can be used profitably are numerous, and our utilization rate remains high. This is important to real-ize profitability.

As tremendous as these aircraft systems might be, they are big and very expensive. This makes them ill-fitted for many remote sensing applications. Flying under 1,200 feet, flying over small areas of high or immediate importance, flying over oil and gas pipelines once a month, or performing detailed infra-structure mapping are all either impos-sible, unsafe or too expensive to do with manned systems.

Send in the drones

Drones are technologically sophisticated remote sensing platforms capable of autonomous flight. Today, for the first time in history, anyone can fly drones in the national airspace. We have entered a new age of “personal remote sensing.” Drones are small, inexpensive technological marvels. Almost unbelievably, drones fly themselves. The remote sensing and mapping technology bundled with them enable non-mappers to pro-duce mapping products.

The barriers to entry into flight and remote sensing and mapping are evaporating thanks to drones. Using drones, we can now fly very low. Mapping small areas is now affordable. Mapping infrastructure from the air is now possible and puts no lives at risk. The number and types of remote sensing and mapping applications have multiplied thanks to unmanned aerial systems. Hurray!

But, the regulatory cords tying drones to a perpetual state of being grounded are effectively neutering their chief societal benefits and preventing the most profitable remote sensing and mapping applications. Although some restrictions of the Section 333 exemptions have been lifted or are less onerous, there are still major impediments to commercial oper-ations of drones in the U.S.

One of the most exciting, and potentially important, parts of Part 107 is the new concept of waivers from these restrictions.

The waiver option

“Because UAS constitutes a quickly changing technology, a key provision of this rule is a waiver mechanism to allow individual operations to deviate from many of the operational restrictions of this rule if the administrator finds that the proposed operation can safely be conducted under the terms of a certif-icate of waiver,” the new FAA ruling states. This presents intriguing possibilities, but the FAA has yet to describe how these will be granted and under which scenarios a professional mapper could receive a waiver.

We will have to wait and see how these will work. If waivers can be applied for online and be obtained in 72 hours with a reasonable safety plan that minimizes the risk of harm to people or prop-erty, the door could be thrown open for commercial opportunities for drones.

Think VLOS

The most limiting operative regulation is that drones must be operated only within visual line of sight (VLOS). That is, the operator must fly the drone only to the limit of his or her own, unaided sight. This means that on a clear day, the drone cannot fly more than one-half to one mile away. For all practical purposes, because small UAS are so small, they can’t be observed if much over one-half mile away and certainly not if they go around a curve a few yards away. VLOS flight restrictions are the most distressing obstacles to profitable remote sensing and mapping applications.

“Corridor mapping” is needed for gas and oil pipelines, highways, railroads and transmission lines. Long corridors that stretch for dozens, if not hundreds, of miles need mapping and monitoring. Although today’s small drone systems are technically capable of producing quality, accurate information for these markets, they cannot do so profitably because of the VLOS flight restrictions.

VLOS regulations are so restrictive they have even impacted how drones are manufactured. The majority of the first-generation drones are fueled by batteries. They have a reach of 15 minutes to 60 minutes of flight time on a single charge. To “refuel,” they must be flown back to their take-off location to swap out their batteries. This renders their effective geographic reach to miniscule distances (a max-imum of one square mile). This, in turn, severely limits the number and type of profitable applications.

Sure, some profitable remote sensing and mapping applications exist, but they are few compared to the opportunities afforded manned systems, and even less when compared to the potential that exists for small UAS. Manufacturers have responded with battery systems because no one needs a drone with a six-hour flight time if all it can do is buzz around like a gamboling sweat bee at a picnic and never venture far away.

But it’s worse than that. If flying a corridor containing trees or hills, the drone can’t be flown “around the corner” behind trees or hills or around a bend in a road or track. This effectively renders drones impractical for virtually any type of corridor remote sensing and mapping with the exception of special case scenar-ios where cost is not an obstacle.

Part 107 waivers

Part 107 waivers from this restriction offer some hope that, at least in unpop-ulated, rural areas, commercial remote sensing operations using drones may be allowed beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS). As mentioned earlier, this is a positive development, but the FAA has not described how these waivers will be granted, how long they will take or just how likely a waiver from the VLOS restriction can be granted for any particular use.

A second major regulatory restraint is that flights above 400 feet are gener-ally not allowed. For most remote sens-ing and mapping applications, flights at 400 feet above ground level (AGL) are simply too close to features on the ground to be practical. The new Part 107 rule preserves this limit but allows for the possibility of a waiver.

Another importunate regulation is that “all flight operations must be conducted at least 500 feet from all non-participating persons, vessels, vehicles and structures.” While flying at 400 feet AGL, the operator cannot fly over a highway, or people or houses without passing within 500 feet of these features. The most conservative rendering of this regulation forces the interpretation that if even one person or car might pass under the drone, the flight should not be conducted.

A welcome relief from Part 107 allows operators to use drones to inspect structures that may extend more than 400 feet into the airspace as long as

the drone stays within 400 feet of the structure. The loss of this restriction is important, because it opens up an important remote sensing application for drones that will save many lives that are put at risk during daily inspections of structures.

Populated areas

Unfortunately, Part 107 includes a complete prohibition of flying over any person not “directly participating” in the drone operation. Again, waivers are theoretically possible if the operator can demonstrate that the operation will not decrease safety. It remains to be seen if this will ever be possible.

Many drone operators are less than excited about these regulations and fly wherever they choose. Part 107 clearly disallows flying over people not involved in the operation of the drone. The Section 333 exemptions used unclear language and could be interpreted to allow some flights over some people.

So at least Part 107 clarifies the FAA’s position: No operations over people. But waivers are an unproved possibility.

Part 107 allows the operation of a drone from a moving vehicle (except aircraft) in sparsely populated areas.

This was not allowed with Section 333. This is a very positive step forward and will enable a number of new, important commercial operations.

Part 107 does not include a liability insurance requirement. But there are legitimate professional concerns about operating drones in this manner even if the local FAA authorities have given a nod to such operations. A firm’s professional liability insurance may not cover an incident if the drone operations do not comply with the regulations. Because these regulations have not been legally tested and because of the consid-erable ambiguity with terms like “congested,” “populated” and “persons,” an insurance company may have the stand-ing to deny claims because the operator was in violation of the FAA regulations as written. The wise professional will operate drones using the most conser-vative interpretation of the regulations so as to avoid liability for personal or property damage.

The future?

Our future in the aerials services busi-ness will be one of flying drones. Over 1 million were sold in the U.S. last Christmas. After the obdurate regula-tory burden is lifted—that’s optimism on my part—the landscape will be vastly different from today. Drones will increase across the land and sky. BVLOS rules and softer regulatory language are being studied now.

No one, not even the FAA, can say when drones can be routinely sent off over the horizon to perform remote sensing. In three to five years? It’s anyone’s guess.

In the near future, we will probably not own any battery-powered aircraft. Their geographic reach and sensor payload capacity is simply too limiting. The next-gen remote sensing drones will be designed with gasoline- or fuel cell-powered engines. They will fly from four hours to days on end. They will not be landed and refueled at air-ports but at other waystations located everywhere, and specially designed for autonomous drones.

Although the new FAA final rule is a reasonable compromise between com-peting public interests, it still restricts the bulk of commercial opportunities for drones. It may still feel like swim-ming in a coffee cup at the beach. The tremendous potential of drones for good remains confined to this one speck on the beach of limitless opportunities.

Mike Tully is president and CEO of Aerial Services Inc.

Recommended Reading

Paisie: Crude Prices Rising Faster Than Expected

2024-04-19 - Supply cuts by OPEC+, tensions in Ukraine and Gaza drive the increases.

Brett: Oil M&A Outlook is Strong, Even With Bifurcation in Valuations

2024-04-18 - Valuations across major basins are experiencing a very divergent bifurcation as value rushes back toward high-quality undeveloped properties.

Marketed: BKV Chelsea 214 Well Package in Marcellus Shale

2024-04-18 - BKV Chelsea has retained EnergyNet for the sale of a 214 non-operated well package in Bradford, Lycoming, Sullivan, Susquehanna, Tioga and Wyoming counties, Pennsylvania.

Defeating the ‘Four Horsemen’ of Flow Assurance

2024-04-18 - Service companies combine processes and techniques to mitigate the impact of paraffin, asphaltenes, hydrates and scale on production—and keep the cash flowing.

Santos’ Pikka Phase 1 in Alaska to Deliver First Oil by 2026

2024-04-18 - Australia's Santos expects first oil to flow from the 80,000 bbl/d Pikka Phase 1 project in Alaska by 2026, diversifying Santos' portfolio and reducing geographic concentration risk.