Offshore wind provides an attractive decarbonization solution since oil and gas majors already have similar skills and technology from operating offshore rigs, Marcelo Ortega, Rystad Energy, said. (Source: Dennis Gross / Shutterstock.com)

Texas is leading the U.S. in solar and wind development with almost 38 gigawatts (GW) of operational and under-development capacity, according to Rystad Energy senior renewable analyst Marcelo Ortega.

Speaking at the Renewable Energy Pavilion at the 2023 NAPE Expo, Ortega explained to the audience how impressive Texas’ current renewables energy capacity is—despite being an oil-producing state—and the potential for future growth and investment in the renewables sector.

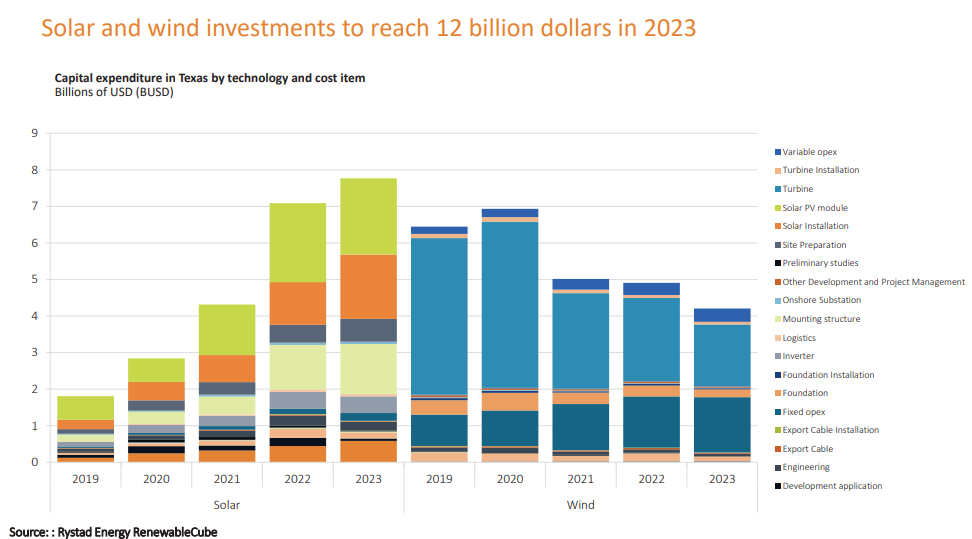

“If it were its own country, Texas would be No. 8 in terms of [renewables] capacity, above Italy,” Ortega explained. “There’s $12 billion coming into the state this year for solar and wind development.”

In fact, during March and April 2022, wind was the No. 1 resource of the Texas grid, Ortega said. This, he continued, shows that in the state of Texas, renewables, especially wind, are cheap enough to displace gas, even in a gas-producing state.

“Not even California is at that level where renewables overtake their oil and gas and nuclear power production,” he said, “and Texas is already at this stage.”

Texas’ appeals

Several factors led to the rapid development of wind and solar in Texas. The deregulation of the Texas power grid has enticed many developers to invest there, mostly due to a less bureaucratic red tape.

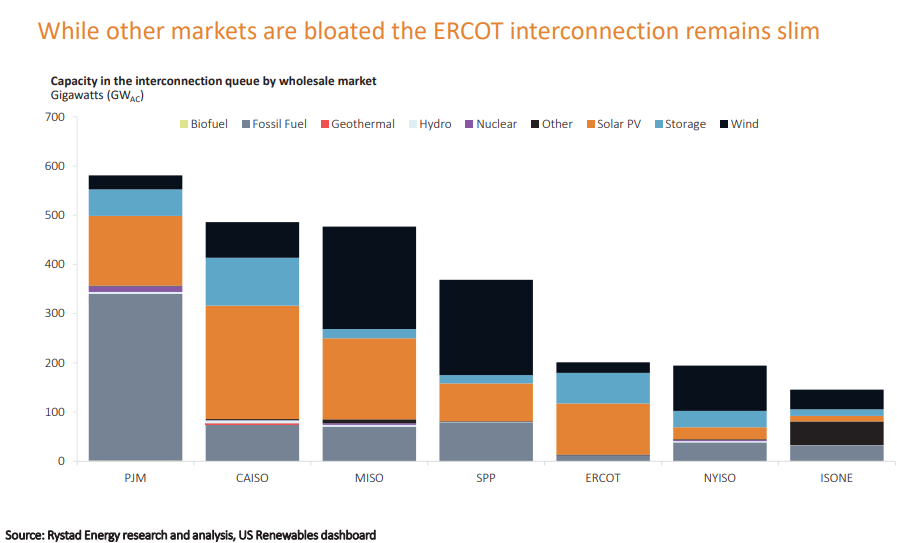

Before any new developer can add capacity to the grid, they have to receive permission from the grid operator and tests have to be run to determine if the transmission lines can support the new capacity. This process becomes a bottleneck for adding new developments.

“Grid operators were used to maybe producing studies on very few and very large coal plants and gas plants, and now they’re getting requests from hundreds and thousands of smaller solar plants,” Ortega said. “These interconnections are getting loaded, and that is one of the development risks that we see; it’s one of the things that are interrupting the booming renewables growth in America because you cannot put these solar farms, wind farms onto the grid until the studies are performed and you get the green light.”

Comparing the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), Ortega showed that there is a “ridiculous amount of capacity” requesting to connect to the grid, and that the waiting list for CAISO is twice that of ERCOT.

“This means that ERCOT is better at pushing these studies. It’s better at being on time with the studies that developers need,” he said. “So, it has way less of a backlog of projects.”

What this means, he added, is that if you’re a developer, “it would probably be easier and faster to develop in Texas than it would in other states.”

Offshore wind

Oil majors in the U.S. with renewables portfolios vastly prefer solar sources, with about 60% of developing capacity going into that technology. Solar is seconded by offshore wind, at about 17%.

Ortega estimates that by 2028, the global offshore wind capex will surpass the global greenfield capex, and it will surpass the global offshore oil and gas total capex by 2030.

According to his research, the U.S. offshore wind capex is forecasted to overtake offshore oil and gas by 2026, a prediction that is very impressive to Ortega, considering that the U.S. has virtually nothing operational right now.

The projected capacity for 2026 is 21 GW. “It’s [currently] at 400 megawatts, so 0.4 GW, which is nothing,” he said. “Going from that right now to 21 GW in three years is a very impressive endeavor. It’s particularly tough, but things are moving that way.”

And the rich history of offshore oil and gas in the U.S. lends itself well to the growth of offshore wind.

“Offshore wind is growing at increasing rates,” Ortega said. “It’s the preferred, or favorite, technology for a lot of governments to decarbonize their grids. And I think it’s one of the preferred technologies for oil majors because it kind of reminds them of an offshore rig.”

The oil majors have a lot of the skills and technology already in place to lend themselves to establishing and operating offshore wind projects, due to their history with working on offshore rigs, he explained. The offshore wind projects are larger than most of the solar projects and they’re difficult to develop—all aspects that offshore rigs are well-equipped to manage.

“I would say it’s easier to do that than going from onshore wind to offshore wind,” Ortega said.

Recommended Reading

Rhino Taps Halliburton for Namibia Well Work

2024-04-24 - Halliburton’s deepwater integrated multi-well construction contract for a block in the Orange Basin starts later this year.

Halliburton’s Low-key M&A Strategy Remains Unchanged

2024-04-23 - Halliburton CEO Jeff Miller says expected organic growth generates more shareholder value than following consolidation trends, such as chief rival SLB’s plans to buy ChampionX.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Americas

2024-04-23 - The final part of Hart Energy E&P’s Deepwater Roundup focuses on projects coming online in the Americas from 2023 until the end of the decade.

Ohio Utica’s Ascent Resources Credit Rep Rises on Production, Cash Flow

2024-04-23 - Ascent Resources received a positive outlook from Fitch Ratings as the company has grown into Ohio’s No. 1 gas and No. 2 Utica oil producer, according to state data.

E&P Highlights: April 22, 2024

2024-04-22 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a standardization MoU and new contract awards.