(Source: Hart Energy; Shutterstock.com)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the April 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

It’s not hard to recall times when we’ve heard predictions of an upturn in M&A activity, only to see the next couple of quarters go by with little M&A of substance. In 2019, setting aside Occidental Petroleum Corp.’s purchase of Anadarko Petroleum Corp., M&A activity came to just half of the average M&A total of the past 10 years, according to Enverus data.

Energy’s performance in the broader market hasn’t helped. The energy sector weighting in the S&P 500 has fallen below 5%, and energy has been the worst performing sector in five of the past six years. But many observers have cited the need for greater scale in order for producers to compete, especially when energy investors increasingly prioritize returns and stock buybacks over growth.

What’s tough to determine is the track record of M&A activity as regards the delivery of synergies that are expected to accrue to a transaction over time and help make mergers more attractive for investors.

Some have strongly argued that projected synergies fail to materialize, making shareholders shy away from stocks involved in M&A. Others point to synergies coming in close to, or above, projected levels, typically tilted to cuts in general and administrative (G&A) expenses in the first year of a merger, followed by operational synergies as the two parties fully integrate their practices.

A study by another industry observer shows a split of roughly 50:50 in terms of those mergers that did and those that did not deliver on the synergies that investors expected at the time of the merger.

Exceeding initial estimates

Steve Trauber, head of global energy investment banking at Citi, is adamant that the trend is in favor of synergies meeting or exceeding levels announced at the time of a merger.

“Synergies are ending up being larger than when they were announced,” he said. “Diamondback Energy [Inc.] exceeded its projected synergies in its merger with Energen. And at the end of the day, the Occidental-Anadarko merger will deliver more synergies than they announced. More recently, the Parsley Energy [Inc.] merger with Jagged Peak [Inc.] will also exceed its projected cost savings.”

Lengthening the list to include other recent combinations—PDC Energy Inc. with SRC Energy Inc. and WPX Energy Inc. with Felix Energy II—“I’ll bet that those will also exceed their synergy numbers,” he added. “I’ve been in there to talk to them. I’ve heard it straight from the CEOs’ mouths. They’re doing a really good job to get rid of costs. They have to; that’s what these deals are all about.”

Trauber attributed the likelihood of finding more synergies than when a deal was first announced to a couple of factors. “Some of it could be a desire to underpromise and overdeliver,” he said. “Maybe they also recognize that there’s likely to be a few hiccups along the way. But they want to be able to tell the market at the end of the day that they’ll be able to exceed their goal.”

Also, in a weaker commodity environment, he continued, “you’re able to take out more costs. But you often need a catalyst to do it. There are a number of upstream companies today that would privately admit they have significant costs they could still take out. There’s nothing like a deal to have to examine and take out your own costs. And so they end up having more synergies than they thought.”

Trauber pointed to the line-by-line detail employed by Diamondback to provide transparency in progress being made on synergies in its merger with Energen. (Citi acted as exclusive advisor to Diamondback on the deal.) Synergies were achieved on a larger scale and at a faster timetable than expected on announcement of the deal, he said. “They’re achieving them, plus some.”

As for the timing of synergies, most of the G&A savings occur in the first year, but these are offset in part by severance and possibly relocation costs, “so you don’t get the full-year benefit in year one,” said Trauber. Operational synergies occur more slowly than with G&A, but they generally materialize to the tune of 80% to 100% in the second year after an acquisition, he estimated.

In terms of the capital efficiency of its corporate structure, Trauber pointed to Diamondback having “put together a really interesting organization. They’ve got a midstream business, they’ve got a royalty business and, of course, the E&P business. They have a lot of ways to make acquisitions and to move the assets around to achieve the highest valuation for their assets.”

Generally, potential synergies can typically be captured by increasing volumes through existing midstream assets or through water handling and water disposal assets, said Trauber.

In addition, cost savings can be expected from greater scale in negotiating drilling rig contracts and pressure pumping services. “And greater scale should give you more flexibility to move rigs and crews around.”

In particular, greater scale in terms of contiguous acreage should allow for drilling with longer laterals, typically translating into greater efficiencies in drilling operations, said Trauber.

‘Less than clear’ synergies

Others offer a degree of skepticism surrounding synergies realized historically in mergers. Often, the degree to which expected synergies materialized “has generally been less than clear, maybe because companies haven’t been hitting their numbers,” said one seasoned energy investment banker that agreed to speak anonymously. “The companies have typically been fairly opaque on that.”

On the part of the investment community, “there’s a general thesis that a lot of the so-called synergies that they’ve heard over the past several years from E&P companies have really not come to fruition,” he said. In specific areas, such as operational synergies, the “buy-side” has viewed E&Ps’ track record of delivering synergies projected at the time of announcement as “overly optimistic.”

As a result, he said, the “buy-side is generally willing to give companies immediate, hard dollar synergies at closing, which are made up mainly of G&A savings. There have also been projected synergies related to operating costs, greater efficiencies, longer laterals, procurement of services, lower supply chain costs, etc., but the market has pretty much dismissed those expected savings.”

Their attitude is, “I’ll believe it when I see it. I’ve heard that story too many times,” recounted the energy investment banker.

In the case of a significant premium being paid by the acquirer, G&A savings are likely to justify part of the takeover premium but remain “far, far shy of accounting for the entire premium paid,” he continued. “And the other synergies that the acquirer used to justify payment of a big premium are assumed to in large part never come to fruition. That’s the general view out there.”

Outsized claims related to synergies in one high-profile merger may have contributed to the recent argument in favor of very low premium, or zero premium, mergers, according to the banker. In that vein, he pointed to what was generally applauded as a zero premium merger between two Denver-Julesburg Basin players, in which PDC Energy acquired SRC Energy.

In addition, the energy investment banker highlighted the success of Diamondback in attaining its projected synergies as well as its accompanying transparency in tracking them for investors. “They’ve done an excellent job—as good as anyone,” he commented.

Financial versus operational synergies

“The challenge with synergies is that it’s a very large bucket that encompasses a number of variables,” said Mark Viviano, head of public-equity investing at Kimmeridge Energy Management Co. “Where the synergies have clearly materialized in a number of deals is in the area of financial synergies, particularly around corporate G&A and reducing head count.”

Synergies in the above areas are “both identifiable and trackable” over time, according to Viviano, and these synergies “have largely materialized and in some cases been even better than expected.” On the other hand, investors have struggled with most operational synergies, which “are not very transparent and not very trackable within reported financial statements.”

The latter lack of transparency has, in part, helped create a “perception that the level of synergies has been disappointing,” he continued. In addition, he cited a number of instances in which high-profile acquirers have run into post-acquisition “operational challenges,” leading to results that fall short of company guidance or sell-side consensus expectations.

“If you look at high-profile deals done over the past two years, particularly in the Permian Basin, some of the acquirers ended up disappointing,” said Viviano. That has led to a “perception that the acquisitions themselves elevated operational risk. And the elevation of operational risk can come from potentially not understanding the asset base being acquired or a struggle in organizational integration.”

Concho Resources Inc. was cited by Viviano as one Permian producer that had to revise its operational strategy from what it had previously communicated to investors.

Concho’s management team had been “touting the merits of the deal based on moving to larger pad completions,” he said. “And, a year later, they were dialing back the size of the projects. Of course, we’re talking about subsurface, where there are a lot of unknowns and management doesn’t have all the information. But when something like that happens, it’s damaging to the credibility of the industry.”

In turn, any synergies laid out by companies at the time of the merger “become a moving target, because you’re changing the way that you’re developing the assets,” Viviano said. “And going back to the earlier point, there are no variables you can track; there are no reported numbers in the financial statements. And unlike G&A, this creates an opaque view of what actually happened post-acquisition.”

While G&A savings may be fully recognized within 12 months, operational synergies are “very case-specific,” according to Viviano. Operational synergies may vary depending on supply chain inputs, for example, or on a specific methodology that is used to drill wells. Increases in efficiencies in these areas may be implemented in the first six to 12 months, he said.

“However, some synergies, such as those involved in the strategy around developing an asset, including changes in the size of a pad, can take longer. And it’s less clear to the market how effective data,” said Viviano.

While energy stock prices have factored in some linkage between synergies delivered by a company as compared to prior market expectations, other market forces are also at work, noted Viviano. “A lot of it is the market’s overall view of energy and the E&P sector specifically. It’s always hard to disaggregate how much is company specific versus sector specific under performance,” he added. “I think the template going forward for successful acquisitions is going to be deals that enhance the free-cash-flow profiles of the companies and the measurable return of capital to shareholders,” said Viviano. “Ultimately, the litmus test for a business is how much cash is returned to the investor. And we haven’t seen a deal in shale that has materially changed the cash return to investors.”

According to Kimmeridge, the industry goal should be to strive toward a capital allocation framework of spending about 70% of cash flow in a given year and returning the balance to investors via dividends and stock buybacks. “The industry has to provide visibility as to how it will get to those types of re-investment to attract shareholders back to the sector,” said Viviano.

Strategic sense

Andy Rapp, co-founder of energy investment bank Petrie Partners, underscored the important role that synergies may play in a merger but cited strategic rationale as the critical factor in making mergers successful over the long term in today’s tough energy environment. “The deal has to make strategic sense,” according to Rapp. “You don’t want to have to rely on the synergies to carry the deal. That said, in this challenging environment where every penny of improved margin counts, you can look at the synergies as a real component as to why a transaction might make sense, why it may provide substantial savings and be a material improvement in the economics of the combined entity.”

G&A and operating expense synergies have “always been something that we’ve tracked and modeled in transactions,” he said, adding that the net present value (NPV) of the asserted capex has also become a focus and can be viewed as having a certain asset value.

“Unfortunately, if all of a sudden you get into an environment where there is limited capital for development and the economics are challenged, and you end up running three rigs instead of four, everything gets delayed, and the NPV gets pushed out,” said Rapp. “The $1 million to $2 million you were going to save per location aren’t as impactful. I think that scenario playing out in prior deals has led to some skepticism on synergies from investors.”

“In this kind of environment, no one is given the benefit of the doubt, especially in these large acquisitions,” commented Rapp.

Looking back at the combination between Cimarex Energy Co. and Resolute Energy Corp., Cimarex had “the luxury that everybody pretty much understood and embraced the strategic fit when they did the transaction. The asset fit was so hand-in-glove,” said Rapp. “Cimarex’s stock has come down with the market, but that’s not because it’s not realizing anticipated synergies or efficiency targets.”

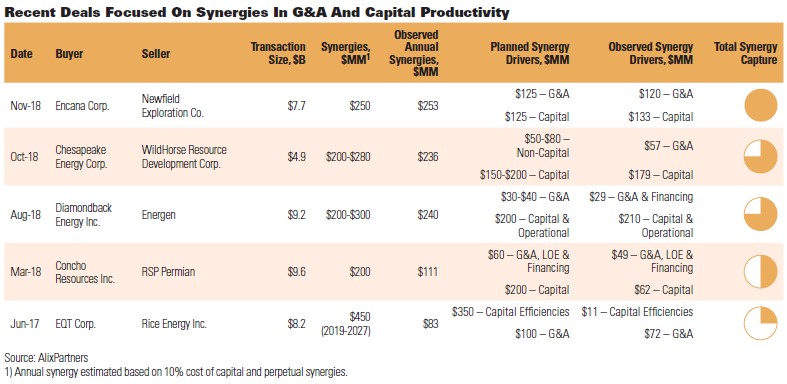

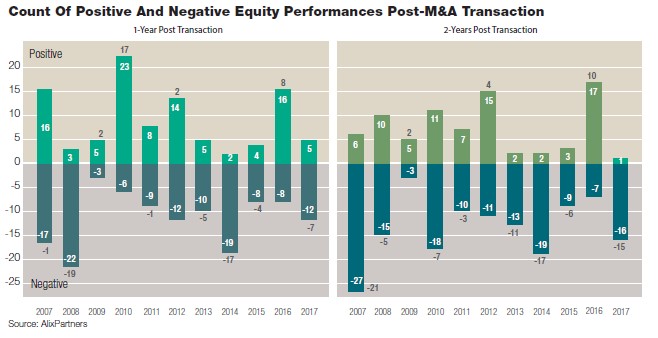

In a recent M&A study, AlixPartners LLP analyzed more than 240 asset and corporate transactions made by publicly traded energy companies over the period 2006 to 2018. The analysis compared the total equity value of the acquiring company and the target prior to announcing the merger against the two parties’ combined equity value at intervals of one year and two years after the transaction.

While commodity prices played a large part in E&Ps’ revenues and profitability, even transactions that were conducted at a time of relatively stable commodity prices showed that M&A was “no panacea,” according to the study. In terms of equity value, there was a roughly 50:50 split between transactions that were value accretive and value destructive, after both one and two years post-deal closing.

In a more recent study, focusing on a subset of five mergers announced in 2017 to 2018, the findings were somewhat similar, according to Bill Ebanks, managing director in AlixPartners’ energy practice. “We went back and tried to track what companies were planning to do in terms of projected synergies and what it appeared they were doing in terms of delivering on their synergies,” said Ebanks. “Our findings indicated three of the five look to be on track to deliver in a range of expected synergies they announced, while two looked like they were trailing their targeted synergies.”

The three mergers that looked like they were “in the ballpark” as regards expected synergies were: Encana Corp. and Newfield Exploration Co.; Chesapeake Energy Corp. and WildHorse Resource Development Corp.; and Diamondback Energy and Energen Corp. The two that looked like they were may be more challenging were: Concho Resources Inc. and RSP Permian Inc.; and EQT Corp. and Rice Energy Inc.

In its deeper dive into the five E&Ps, AlixPartners sought whatever assumptions were available on “activity levels that drive the synergies that you may be able to capture, including how much capital you deploy, how many rigs you run, how much footage you drill, etc.,” said Ebanks. “If those things don’t materialize as expected, it’s hard to deliver the synergies that you promised.”

In instances where E&Ps provided projected synergies over several years, the study translated the targets into annual dollars for purposes of comparability. Present values assumed a 10% cost of capital.

Captured synergies

“If you look at what was planned versus what was actually captured, most of the operators appear to have captured their G&A synergy,” said Matt McCauley, director in AlixPartners’ energy practice.

For example, Encana-Newfield had a target of $125 million and, based on its most recent 10-Q, has an annual run rate of $120 million of savings, which “seems in line with what the company projected its G&A synergy to be,” said McCauley. As for Chesapeake-WildHorse, the company provided guidance of $50 million to $80 million, and based on the most recent financial statements is at a run rate of $57 million of G&A savings, he added.

“Most of the time, G&A is a very near-time item that companies control and can usually take action on quickly as they integrate the organizations,” said Ebanks. “We would expect the full run rate of a G&A target to be achieved within the first year post-transaction. If we’re involved in the merger integration activity following an M&A transaction, we’d aspire to lock in the organizational synergies in first six to nine months, if not sooner, so we’re at a full run rate benefit by the end of year one.”

On operational synergies, or the “capital efficiency” side, results were more varied. Mergers consummated by Encana, Chesapeake and Diamondback all appear to be on track to achieve their targets, the study indicated. However, those led by Concho and EQT appear to have had annualized capital savings targets of $200 million and $350 million, respectively, “and in both cases it is difficult to see those results being achieved at this point,” said McCauley.

Parent-child issues related to working out optimum spacing of wells “may have caused Concho to pause, take a step back and slow down its capital investment last year in order to eventually optimize its financial results,” said Ebanks. “Concho may not deploy as much capital as it probably thought when it first bought RSP,” he continued. “And it’s hard to achieve the synergies or capital efficiency if you’re not going to spend as much capital in the first place.”

“When you’re talking about a present value benefit of as much as $2 billion, so much of that benefit comes in the first two or three years,” said McCauley. “If you decelerate your capital plan, or if you aren’t able to operationalize the capital plan, that has a material impact on the PV [present value]. That may be a factor in what we’re seeing in the instances of Concho and EQT.”

Setting targets

One of the takeaways from the study, according to Ebanks, is that “those companies that are clearly setting targets and measuring themselves consistently against those targets over the course of the following year or two, post-transaction, seem to be the ones that also are clearly showing the benefits they got from these transactions.”

Those companies reaping benefits from synergies appear to be doing it through one of two main ways, said Ebanks.

One is building “local scale, which allows them to enjoy purchasing power from suppliers and to leverage the expertise on the acreage they already own, and to then apply it to the offset acreage that they pick up,” he said. “Another is being fundamentally better operators. They have an advantaged capability they can apply to someone else’s acreage and drill and complete wells better than others.”

In looking at the premiums paid in the five mergers in 2017 to 2018, acquirers paid a range of premiums of 20% to 35%, said McCauley. Since then, premiums have been declining, even as “some of the healthier companies are interested in acquiring—but on a value basis of maybe closer to 20% or, in some instances, a zero premium in the case of distressed companies.”

The obstacle to transacting mergers could in part be due to the continued volatility in the commodity prices, according to McCauley.

Takeover premiums in energy are markedly lower than in the broader market, he said, “and part of the reason could be due to the volatility in prices,” he added. “If you don’t know that you’ll be able to capture the synergies because of the uncertainty as to commodity price and/or pace of development, then the premium is going to be correspondingly lower.”

SIDEBAR

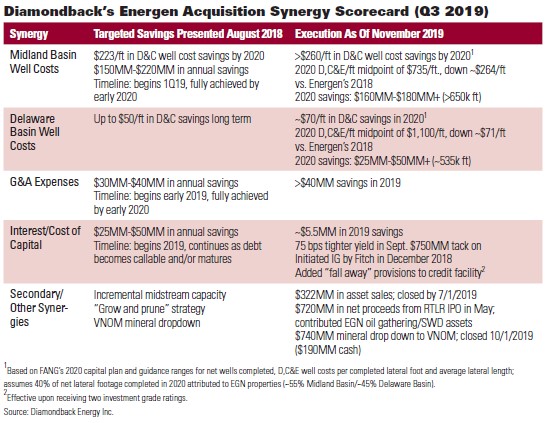

Cutting Costs At Diamondback

Diamondback Energy Inc. has provided periodic updates on its integration with Energen Corp. in an effort to shake off a suspicion that synergies would not materialize. For example, in a PowerPoint presentation accompanying its third-quarter 2019 earnings release, Diamondback compared its execution on synergies as of November of 2019 against the savings it targeted as of its August 2018 acquisition of Energen.

In terms of drilling and completion (D&C) costs incurred for wells in the Midland Basin, Diamondback had projected cost savings of $223 per foot at the time of the acquisition. Cost savings were projected against a benchmark of $999 per foot for Energen in second-quarter 2018. In its November 2019 update, Diamondback estimated D&C costs at $760 per foot for the full-year 2019.

The $760 per-foot update represented a drop in D&C costs of $239, an improvement over the original $223 per-foot estimate. In a subsequent February 2020 presentation, Diamondback lowered its D&C cost estimate again to a 2020 mid-point of $735 per foot, for a further $25 per foot in projected cost savings. Diamondback estimated 2020 cost savings at $160 million to $180 million before the two updates.

In the Delaware Basin, against a second-quarter benchmark of $1,171 D&C costs for Energen, there has similarly been a two-step drop in costs and increase in savings. Combined, the two represent a drop in costs to a 2020 midpoint of $1,100 per foot, for savings of $171 per foot. Once described as an estimated $25 million to $50 million in “secondary” synergies, these are now viewed as “primary” synergies.

Other factors are easier to track. By early 2020, Diamondback expected to bring down G&A expenses by $30 million to $40 million. By November 2019, the company had surpassed the $40 million mark. Savings on interest payments have progressed toward a goal of $25 million to $50 million in annual savings, as the company’s credit rating was upgraded to investment grade, and it was subsequently able to refinance its debt in late 2019. Diamondback had achieved $5 million of interest savings through November 2019.

Recommended Reading

TPH: Lower 48 to Shed Rigs Through 3Q Before Gas Plays Rebound

2024-03-13 - TPH&Co. analysis shows the Permian Basin will lose rigs near term, but as activity in gassy plays ticks up later this year, the Permian may be headed towards muted activity into 2025.

US Drillers Add Most Oil, Gas Rigs in a Week Since September

2024-03-15 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by seven to 629 in the week to March 15.

US Drillers Add Most Oil Rigs in a Week Since November

2024-02-23 - The oil and gas rig count rose by five to 626 in the week to Feb. 23

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Three Weeks

2024-02-02 - Baker Hughes said U.S. oil rigs held steady at 499 this week, while gas rigs fell by two to 117.

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for Third Time in Four Weeks

2024-02-09 - Despite this week's rig increase, Baker Hughes said the total count was still down 138 rigs, or 18%, below this time last year.