(Source: Shutterstock, HartEnergy.com)

Several factors are contributing to the toxicity of fossil fuel stocks but one factor in particular—a political movement demanding that institutional investors divest their holdings—is a significant long-term driver.

And don’t expect the pressure to let up.

“If we can stop the funding, pipelines and drilling sites cannot go ahead, and fossil fuels will have to stay where they belong: in the ground,” wrote Nicole Leonard of 350.org, an international organization dedicated to ending the fossil fuels era and hastening the transition to an all-renewable powered world.

Is such an approach realistic, given the growing global demand for energy and the enormous challenges that would need to be overcome for solar and wind power to meet those demands?

Doesn’t matter. These folks are coming for the oil and gas industry. They’ve got an effective strategy to strangle the flow of capital to the oil and gas sector, and they are gaining momentum.

“A few months ago, they were talking about the allocation of institutional investors to energy in the Fortune 500 is at a 20-year-plus low,” Jim Rebello, managing director and head of the energy M&A advisory practice at Duff & Phelps, told HartEnergy.com. “There’s a lot of capital that’s not interested in the energy industry.”

There are two primary reasons for this, he said. One is that when people compare returns in energy against other sectors of the economy, they see an underperformer.

“And then this whole movement away from fossil fuels,” he added.

In its 2018 annual report, global energy giant Royal Dutch Shell acknowledged the threat in blunt terms:

“Some groups are pressuring certain investors to divest their investments in fossil fuel companies,” the report said. “If this were to continue, it could have a material adverse effect on the price of our securities and our ability to access equity capital markets.”

Shell cited the World Bank’s plans to stop financing upstream oil and gas projects, as well as reports of other financial institutions that are considering limiting exposure to particular fossil fuel projects. The impact on future projects would not affect Shell alone.

“This could also adversely impact our potential partners’ ability to finance their portion of costs, either through equity or debt,” the report said.

Misery Loves These Companies

The downcycle that began in late 2014 was rough on all but particularly unkind to the oilfield services sector. Revenue plunged 20%, according to Deloitte, and more than 170 oilfield services providers have filed for bankruptcy since 2015.

But Schlumberger Ltd. recovered nicely. From losses of $1.7 billion in 2016 and $1.5 billion in 2017, the 100,000-employee company delivered net income of more than $2.1 billion in 2018. That’s the kind of rebound that investors love. Except they didn’t.

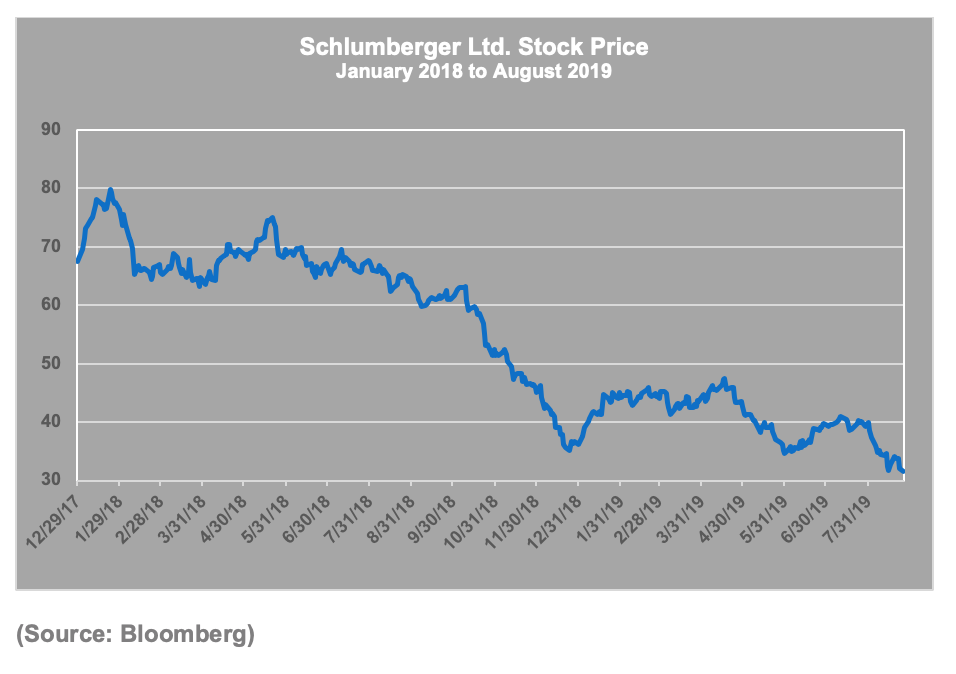

The chart below shows Schlumberger’s share price from the start of 2018 through late-August 2019. During that time, it took a 53.1% hit—60.4% if you calculate from the high of almost $80 in late-January 2018.

Given the company’s performance in 2018, the stock’s 46.5% retreat in value that year could have signaled that investors weren’t convinced Schlumberger could continue to report strong numbers. Visually, that makes sense as the price line mostly lingers below $45 from the start of 2019 to late August.

But Schlumberger’s quarterly reports do not bear out that line of thinking. First-quarter 2019 revenue of almost $7.9 billion beat first-quarter 2018 by about $60 million, and the company cleared north of $400 million. Second-quarter 2019 had similar bright and shiny numbers.

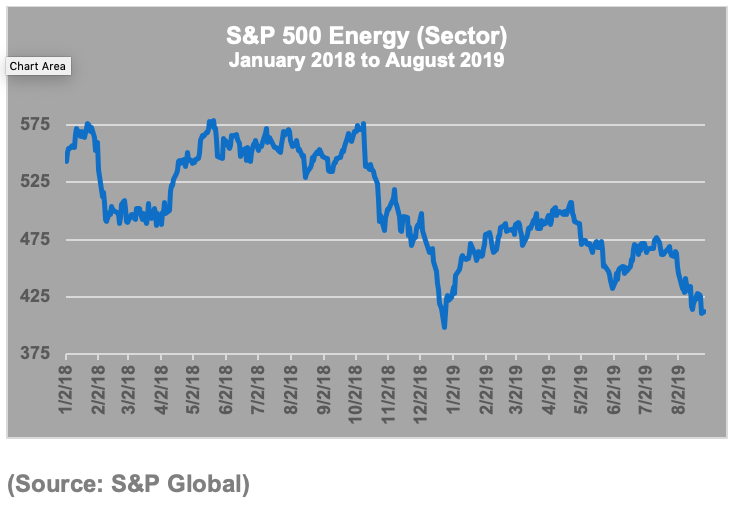

Schlumberger is not alone. The S&P 500 Energy index shows a collective 24% drop in that January 2018 to August 2019 time period.

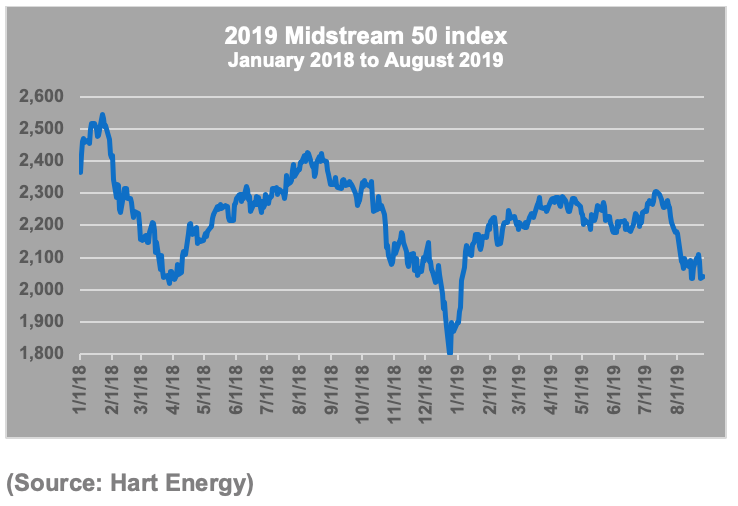

Positive news comes from the midstream sector. Hart Energy’s Midstream 50 index is down only 13.7% in the 20-month time period from the start of 2018. The index comprises the 50 companies that ranked highest in EBITDA during 2018 and is weighted by market capitalization.

However, from the start of 2019 to the last week of August, the Midstream 50 is up 7.6%. That compares to a 4.7% loss for the S&P 500 Energy index in that time period.

By comparison, the broad S&P 500 Index gained 14.8% from the start of the year to the last week of August. That’s an indication that equity markets have responded positively to the strong U.S. economy but not to the energy sector.

What Is The Meaning Of This?

If finance woes were confined to Wall Street, it might be considered a temporary quirk that will work itself out, given the overall healthy environment in the oil and gas space. But middle market M&A is not healthy.

“The ability of leverage to support energy M&A has seen a dramatic pullback,” Rebello said.

It’s not unusual to see caution from traditional lenders following a downturn, he said, but unconventional lenders such as hedge fund managers typically replace them. Their approach is that they could get a higher yield than normal because the market is not very competitive. Alternative lenders, however, tend to take their cues from equity markets with the view that they can sell the business if things don’t work out.

“But because the equity markets have not been supporting energy, [alternative lenders are] not coming into the marketplace,” Rebello said. “So that’s one part of the pullback. You’re not seeing a lot of leverage coming in.”

But it’s not just pressure from grassroots activists. The Green New Deal resolution, proposed by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), is co-sponsored by six Democratic presidential candidates who serve in Congress and supported by three others. A change in administrations away from support of fossil fuels would create uncertainty.

“Uncertainty breeds discounts,” he said. “What we’re seeing is a lot of capital sitting on the sidelines because there’s not a lot of clarity as to where the domestic oil and gas industry is going.”

This Is Gonna Cost

In 2008, a group of university students in the U.S. joined with author and environmentalist Bill McKibben to form 350.org, which is building a global climate movement. The “350” in the name represents 350 parts per million (ppm), which is the level designated by scientists as the target for CO2 in the atmosphere. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated in 2018 that the 2017 level was 405 ppm.

Much of the divestment campaign targets university endowments, with varying success. The University of Maryland has divested fully from fossil fuel holdings, as has the University of Hawaii and the University of Oregon Foundation, among others. Harvard University, with its massive $39 billion endowment, has resisted calls to divest. Yale University has divested, but only partially and even the University of California has limited its divestment to companies engaged in coal and tar sands.

Then there are the high-profile calls to action that are disheartening from the oil and gas perspective:

- Mayor Bill Peduto of Pittsburgh, capital of the Marcellus Shale, wants that city’s pension fund to drop fossil-fuel industry investments;

- The Rockefeller Brothers Fund, a philanthropy derived from the fortune of iconic oil baron John D. Rockefeller, began its divestment in fossil fuels in 2014 and those holdings were down to 1.7% as of 2017; and

- The student paper at the University of Texas at Austin published an editorial earlier this year promoting fossil fuel divestment from the Texas University Fund, which is based in large part on revenue from oil production.

Divestment is an all-or-nothing proposal, though. The option also exists to maintain ownership of stock and try to influence a company’s direction from the inside.

“I think management teams would rather have access to capital with a vocal investor vs. no capital,” Rebello said. “If you have capital and you’re in an uncertain environment, that puts you in a much better position to capitalize on opportunities going forward. The energy M&A market will likely improve; it always has.”

Some opponents, however, have grown disenchanted with the insider option.

“Despite the efforts of shareholders to work with companies to adopt more sustainable business practices, there is little evidence that the largest oil and gas companies have changed their practices to be consistent with the Paris Agreement goal to keep temperature rise well below 2°C,” Arabella Advisors said in its 2018 report on fossil fuel divestment and clean energy investment.

Rebello sees a threat of higher energy prices as the world begins to transition away from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources. A lack of capital necessarily limits the oil and gas industry’s options, making fuel scarcer and more expensive over time.

“The intentions [relating to fossil fuels and renewables] are positive,” he said. “But this lack of investment in the industry as you try to transition potentially results in a dramatically increased cost.”

Recommended Reading

Imperial Expects TMX to Tighten Differentials, Raise Heavy Crude Prices

2024-02-06 - Imperial Oil expects the completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion to tighten WCS and WTI light and heavy oil differentials and boost its access to more lucrative markets in 2024.

Trans Mountain Pipeline Announces Delay for Technical Issues

2024-01-29 - The Canadian company says it is still working for a last listed in-service date by the end of 2Q 2024.

US Expected to Supply 30% of LNG Demand by 2030

2024-02-23 - Shell expects the U.S. to meet around 30% of total global LNG demand by 2030, although reliance on four key basins could create midstream constraints, the energy giant revealed in its “Shell LNG Outlook 2024.”

ARC Resources Adds Ex-Chevron Gas Chief to Board, Tallies Divestments

2024-02-11 - Montney Shale producer ARC Resources aims to sign up to 25% of its 1.38 Bcf/d of gas output to long-term LNG contracts for higher-priced sales overseas.

Silver Linings in Biden’s LNG Policy

2024-03-12 - In the near term, the pause on new non-FTA approvals could lift some pressure of an already strained supply chain, lower both equipment and labor expenses and ease some cost inflation.