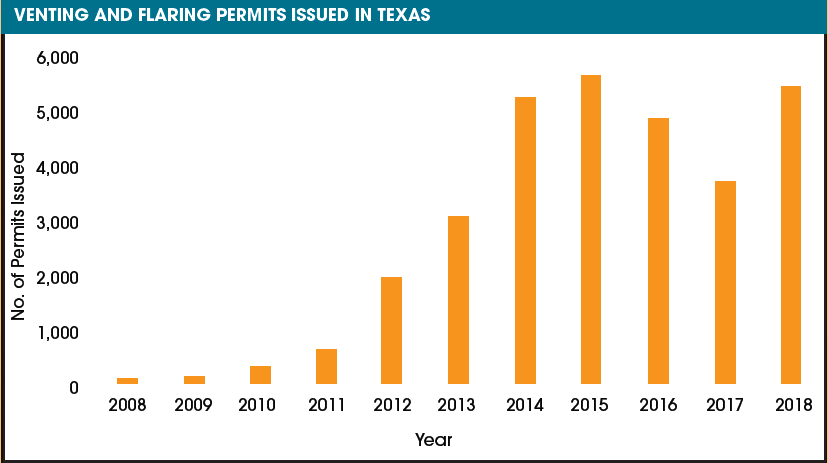

Rule §3.32 of the Texas Administrative Code prohibits flaring of associated gas from initial completion beyond 10 producing days. Exceptions were allowed if a permit application showing cause was approved by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC), the state regulator for the energy industry. RRC records show that 107 venting and flaring permits were approved statewide in fiscal year 2008. That number swelled to 5,488 in fiscal year 2018.

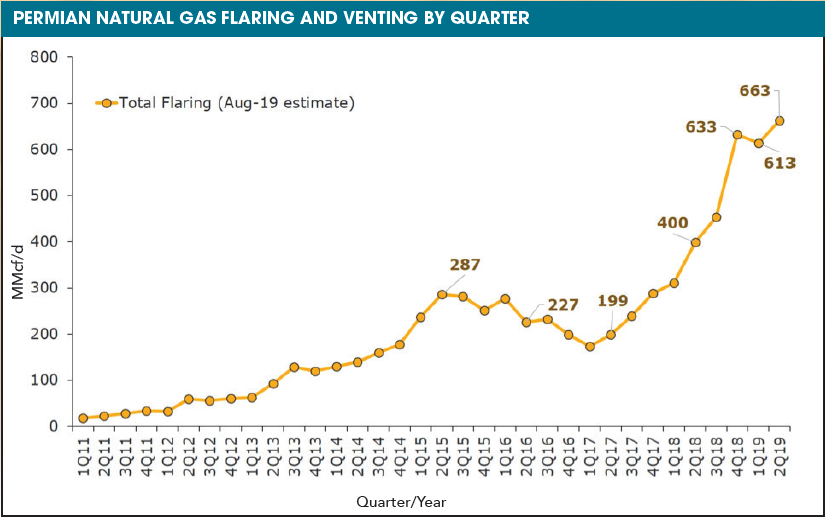

All told, RRC has received and approved more than 27,000 requests from producers to flare gas, many of them in the booming Permian Basin, where gas infrastructure has lagged behind the massive volumes of associated gas that accompany the production of crude.

In many cases, those permits were granted for wells where there was no gas gathering in place or economically feasible. “The business and regulatory question is what to waste, money or molecules?” said Ethan H. Bellamy, senior research analyst at Baird Equity Research.

In April 2019 Bloomberg quoted Pioneer Natural Resources CEO Scott Sheffield telling an energy conference at Columbia University in New York that flaring is “a black eye for the Permian Basin. The state, the pipeline companies and the producers—we all need to come together to figure out a way to stop the flaring.”

So many exceptions were granted that permit requests effectively became notifications by producers to the RRC that they were going to flare. There was also no opposition to any of them, until The Williams Cos. challenged a request by Exco Operating for 69 flares at its operations in Dimmit and Zavala counties in the Eagle Ford Shale. Williams contended that Exco did not need to flare because its Mockingbird Midstream system was nearby.

Exco countered that the cost of building a line to connect with Mockingbird was well above the revenue that would have been generated by selling the gas, which made it cheaper to flare. A contract with Williams for infrastructure near the field was vacated during Exco’s bankruptcy process. The infrastructure remains in place near the field but the valve is turned off.

The two companies also are involved in a related rate discrimination case, the results of which could play a role in the amount of flaring needed should the two companies settle on a rate for Exco’s use of Williams’ nearby pipeline.

On Aug. 6, the RRC decided in favor of Exco by a vote of 2-1, as reported by HartEnergy.com. Commissioners Christi Craddick and Ryan Sitton supported granting the exemption.

“Exco can’t go out today and just turn the valve open because there is no contract in place and it’s not our job,” Sitton said. “We don’t have regulatory capacity over those contracts or signing contracts.”

The lone no vote was by Chairman Wayne Christian. “I have some serious concerns about the frequency and ease with which this commission grants flaring exemptions that may not be associated with the drilling of a completed well,” Christian said later during the meeting. “The price of gas right now is a lot of incentive to flare out of convenience and economics rather than necessity.”

Christian, presiding Aug. 6 over his first RRC meeting as chairman of the three-person commission, said he talked to experts on the flaring issue as well as visited different locations and made phone calls. He said he is concerned about whether the current level of flaring in Texas is in the best interest of the state, the industry and the RRC in the long term.

Reevaluating the Permian

Despite the regulatory setback, Williams continues to keep an opportunistic eye on the region. “We are constantly evaluating Permian projects,” said Micheal Dunn, executive vice president and COO at Williams. “So far we have not seen anything line up with our disciplined approach to capital.” If putting steel into the Permian is not compelling, making use of gas coming out certainly is. “We get 500 MMcf/d of Permian gas via our Brazos joint venture that we have the rights to market. We will find a way to get that gas to the Transco system. For the long haul, LNG operators would find it increasingly valuable to have a header system like Transco in the Gulf Coast region serving their supply needs,” he said.

“Strategically, Williams is bullish on LNG,” Dunn said. “That is really what is driving gas demand. There is also a lot of growth domestically. There is still a lot of coal-fired power generation coming off the grid, even with the amount of new solar and wind power generation. And those will still need gas as a backup. Utilities will have to rely on gas for primary generation in places where renewables are not viable.”

Christian asked RRC staff to gather data on how many wells in Texas have received a flaring exemption that exceeds 180 days that are physically connected to a pipeline and how many of those are still flaring.

“If we’re going to gather some data, I want to be cautious that we don’t gather only a limited selection that may demonstrate a certain thing when there’s really more at play there,” Sitton said.

He added to the request, asking staff to include how many wells are connected to gathering systems, how many of those are connected to processing plants and what are the total capacities of processing plants and pipelines. There is hope that the massive flaring will be diminished by the end of 2020 when several major pipelines start operating.

Economics or waste rule

Exco emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on July 1, securing $325 million in committed financing. Williams’ market capitalization is about $30 billion.

The Williams gas pipeline is about 6 miles from where Exco is producing in Frio County. The cost to treat and connect its facility to the pipeline is about $7.1 million, according to the RRC docket. Net revenue from the remaining reserves is estimated to be about $1.1 million, however, making it uneconomical to build a pipe connecting the Exco lease to the Williams pipeline.

But even if the economics of transport don’t work, other options may exist for a producer. Among those uses, he said, are EOR, electrical generation, small-scale gas-to-liquids and conversion to LNG. Some producers are already trying to make use of gas locally.

Indeed just weeks after the case was decided, Certarus Ltd. struck a flare-gas capture and compressed-gas supply agreement with a “multinational American energy supermajor” to power its electric hydraulic fracturing operations in the Delaware and Midland basins, as reported by HartEnergy.com. Certarus expects to commence CNG supply to the supermajor in the fourth quarter.

“We are seeing an increasing trend within completions to use electric hydraulic fracturing as a means of reducing carbon emissions and achieving cost savings,” said Nathan Ough, vice president of Certarus. The company claims primacy with “the largest bulk CNG trailer fleet in North America.” Based on that first agreement in the Permian, Certarus will displace a minimum of 5.5 MMgal of diesel fuel with CNG with the option for the client to expand to as much as 37.8 MMgal during the term.

Energy companies across North America, including Exxon, via its XTO subsidiary, Diamondback, Shell, EOG Resources, Devon, CNX Resources and Apache, have contracts for electric hydraulic fleets, in some cases with terms up to four years.

Colin Leyden, senior manager for regulatory and legislative affairs for the Environmental Defense Fund, agrees that the issue may come down to the RRC’s definition of waste, which in the past has equated to economic waste when it involves flaring. “I think that goes directly against what most people would interpret the Railroad Commission’s

job is as far as preventing waste and pollution, which is one of their statutory mandates, and I would think it is one of the objectives of having a flaring rule,” Leyden told HartEnergy.com.

Despite the rising amount of flared gas, particularly in the Permian Basin, Leyden said there are some companies with a “culture of commitment to not flare,” investing in pipeline takeaway capacity, redesigning well pads and using gas on site.

Recommended Reading

Wayangankar: Golden Era for US Natural Gas Storage – Version 2.0

2024-04-19 - While the current resurgence in gas storage is reminiscent of the 2000s —an era that saw ~400 Bcf of storage capacity additions — the market drivers providing the tailwinds today are drastically different from that cycle.

Biden Administration Criticized for Limits to Arctic Oil, Gas Drilling

2024-04-19 - The Bureau of Land Management is limiting new oil and gas leasing in the Arctic and also shut down a road proposal for industrial mining purposes.

PHX Minerals’ Borrowing Base Reaffirmed

2024-04-19 - PHX Minerals said the company’s credit facility was extended through Sept. 1, 2028.

SLB’s ChampionX Acquisition Key to Production Recovery Market

2024-04-19 - During a quarterly earnings call, SLB CEO Olivier Le Peuch highlighted the production recovery market as a key part of the company’s growth strategy.

Exclusive: The Politics, Realities and Benefits of Natural Gas

2024-04-19 - Replacing just 5% of coal-fired power plants with U.S. LNG — even at average methane and greenhouse-gas emissions intensity — could reduce energy sector emissions by 30% globally, says Chris Treanor, PAGE Coalition executive director.