Adding pipeline capacity may at times have the effect of eroding the price advantage that was initially sought, ending up in a “Catch 22” situation. (Source: Hart Energy/Shutterstock.com)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the October 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

They say that “timing is everything,” and certainly that can be the case with the differentials, or “diffs,” prevailing between basins. Producers obviously want to capture higher realized prices when they can. But adding pipeline capacity may at times have the effect of eroding the price advantage that was initially sought, ending up in a “Catch 22” situation.

That said, who doesn’t want a sophisticated network of interlocking pipelines that can efficiently carry crude, natural gas and NGL to market?

oil basin,” said Rob

McBride, senior

director, market

intelligence at

Enverus. “If you’re

still making money

on your oil, you

will pay someone

to come in and

take your gas

from you. You can

continue at really

big differentials

on gas.”

In the case of natural gas, where price variations are termed “basis,” one producer recently suffered a price swing of about $1.95 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf) for its natural gas produced in the Permian Basin. The producer’s average realized price in the Permian fell to a negative price of roughly $0.45/Mcf in the second quarter, down from just under $1.50/Mcf in the year earlier period.

Rob McBride, senior director, market intelligence, at Enverus pointed to several instances in which unexpected outcomes have followed plans to alleviate basis blowouts on the natural gas side. In each case, the plans seemed sound at inception—and may have been if conditions had remained unchanged—but ran afoul of changing market dynamics and/or truly unanticipated events.

The Rockies Express Pipeline, or REX Pipeline, was designed to improve Rockies gas prices by selling to the Northeast—until the vast reserves of gas from the Marcellus Shale emerged, he noted. And, with a growing glut of gas in Pennsylvania, traditional long-haul pipelines serving Northeast markets from the Gulf Coast ended up being reversed to carry gas to Gulf Coast and, in time, overseas LNG markets.

A third iteration

Today, in terms of gas produced in the Permian Basin, “we’re on at least the third similar iteration of where this story has played out in the gas market,” according to McBride. However, there is a critical difference to account for the recent “explosion of gas that can’t get out of the basin.” This time, he noted, the underlying market fundamentals are essentially driven by crude oil, not natural gas.

“What distinguishes the Permian from the Rockies and Marcellus is that the latter are both natural gas basins. And when the basis got really bad, there was a pain point at which producers would say, ‘I can’t take it anymore. I’ve hit that breakeven price, these prices are too low, I have to stop.’ They’d endure it for a day, and then they’d start to shut in their wells,” he said.

“But the Permian is an oil basin,” he continued. “For a gas producer, gas is its key product. For an oil producer, gas is a nuisance; the gas is a cost to the oil producer. But if you’re still making money on your oil, you will pay someone to come in and take your gas from you. You can continue at really big differentials on gas. You can continue at seriously negative outright pricing.”

about the

differential

between market

hubs as being

the implied free

market value of

pipeline space,”

said Jesse Mercer,

senior director

of crude market

analytics at

Enverus. “They’ll

move incremental

barrels at

somewhere close

to what their

marginal cost

to ship is.”

On some days, the Waha price in the Permian fell to more than $9/Mcf off Henry Hub, recalled McBride.

For Permian gas, McBride is far from optimistic about a near-term price rebound.

Gas is just ‘collateral damage’

“It’s a disaster, pricing-wise, right now,” he said in mid-July. “It was anticipated, and the conditions will likely continue through the balance of the year. And, depending on how much drilling takes place there, it may persist for another year. Oil is the real story in the Permian; gas is just collateral damage.”

However, there are two pipeline projects underway with enough capacity that they may be able to relieve conditions to some extent, said McBride. These make up the Gulf Coast Express, due to come online this month, and the Permian Highway Pipeline, expected to be in service in late 2020, subject to regulatory approval. Each has capacity of 2 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d).

The Gulf Coast Express, sponsored by Kinder Morgan, is designed to transport gas from the Permian to Agua Dulce. The Permian Highway Pipeline, backed by Kinder Morgan and EagleClaw Midstream Ventures with each holding 40%, is being built to serve “growing market areas along the Texas Gulf Coast,” as well as markets in Mexico.

“There is spare capacity to deliver into Mexico, but they aren’t taking it right now, because there is not enough demand in Mexico for infrastructure projects currently,” commented McBride.

If the overall impact of these various takeaway projects is considered, “the gas story in the Permian does resolve itself over time,” he said. “We’re expecting some relief by the end of 2019. But if production continues to grow, I expect the whole of 2020 will see depressed prices there. On average, the gas price could easily be close to zero.”

One of the key questions on Permian differentials, according to McBride, relates to operators’ threshold to pain: “How well are you doing on your oil operations that you’ll continue to take the pain on gas? To keep producing oil, how much are you willing to pay to have someone take gas away? Everyone is going to have a different pain point as gas disposal costs keep rising on them.”

On the crude side in the Permian, you don’t have to look back far to find a tumultuous period for differentials. Only last year, with pipelines in the Permian running at capacity, differentials in the basin blew out to over $17 per barrel (bbl) below benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) at Cushing, which in turn traded at $6/bbl below Brent, recalled Jesse Mercer, senior director of crude market analytics at Enverus.

Pipeline deficit to surplus

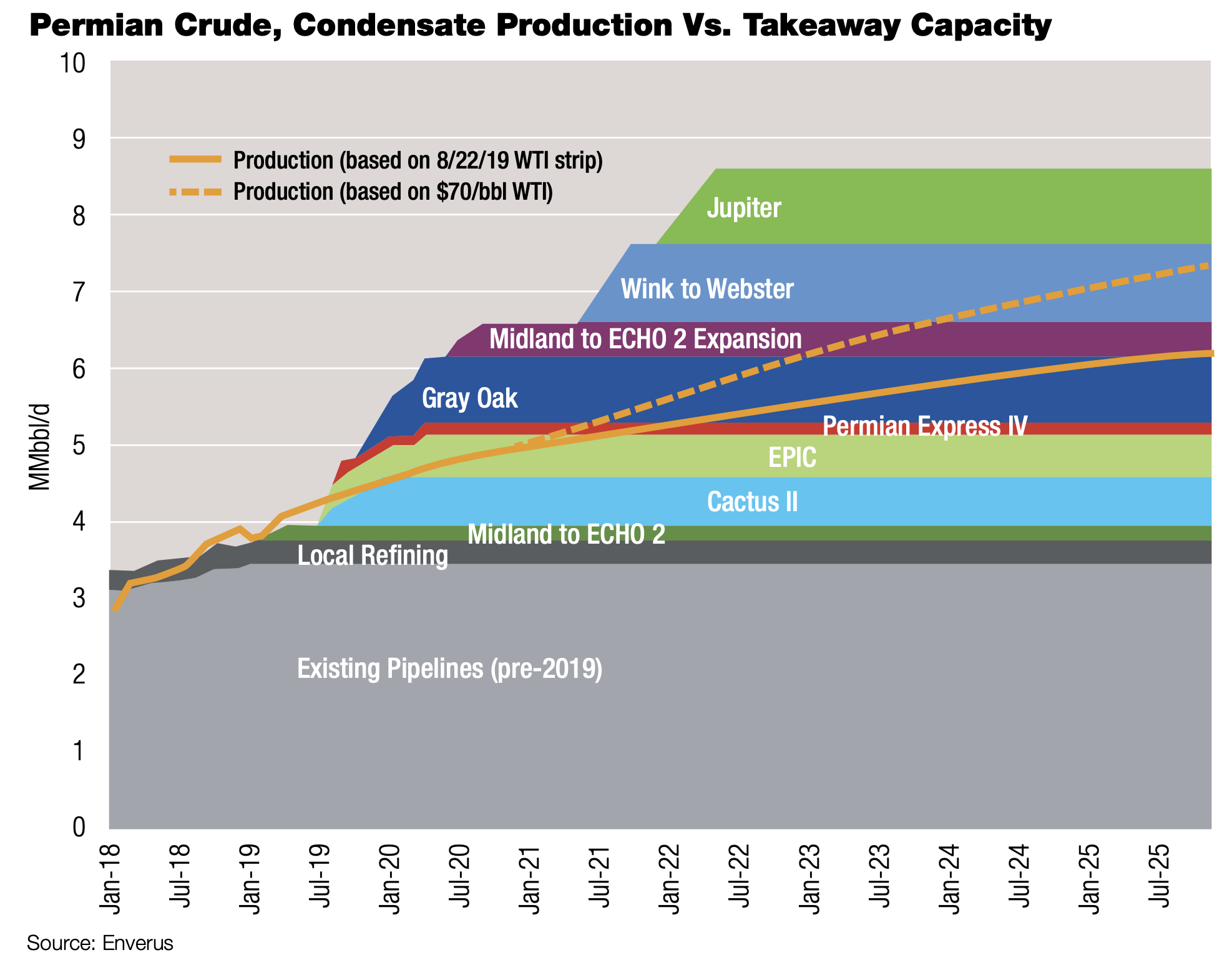

“We go through these cycles of pipeline deficit to pipeline surplus,” observed Mercer. “The pipelines running at capacity in the Permian have spurred a wave of new investment in pipeline projects, many of them starting up now, in the second half of this year. More often than not, when that happens, there’s an overbuild and not enough supply to fully meet all the shipper commitments.”

With new pipeline capacity coming online “over a relatively short period of time, from August of this year through the first half of 2021,” said Mercer, “that’s the situation that we’re looking at right now. You have all these pipeline shippers who have made commitments, usually up to 90% of new capacity, but potentially don’t have enough crude to meet those pipeline commitments.”

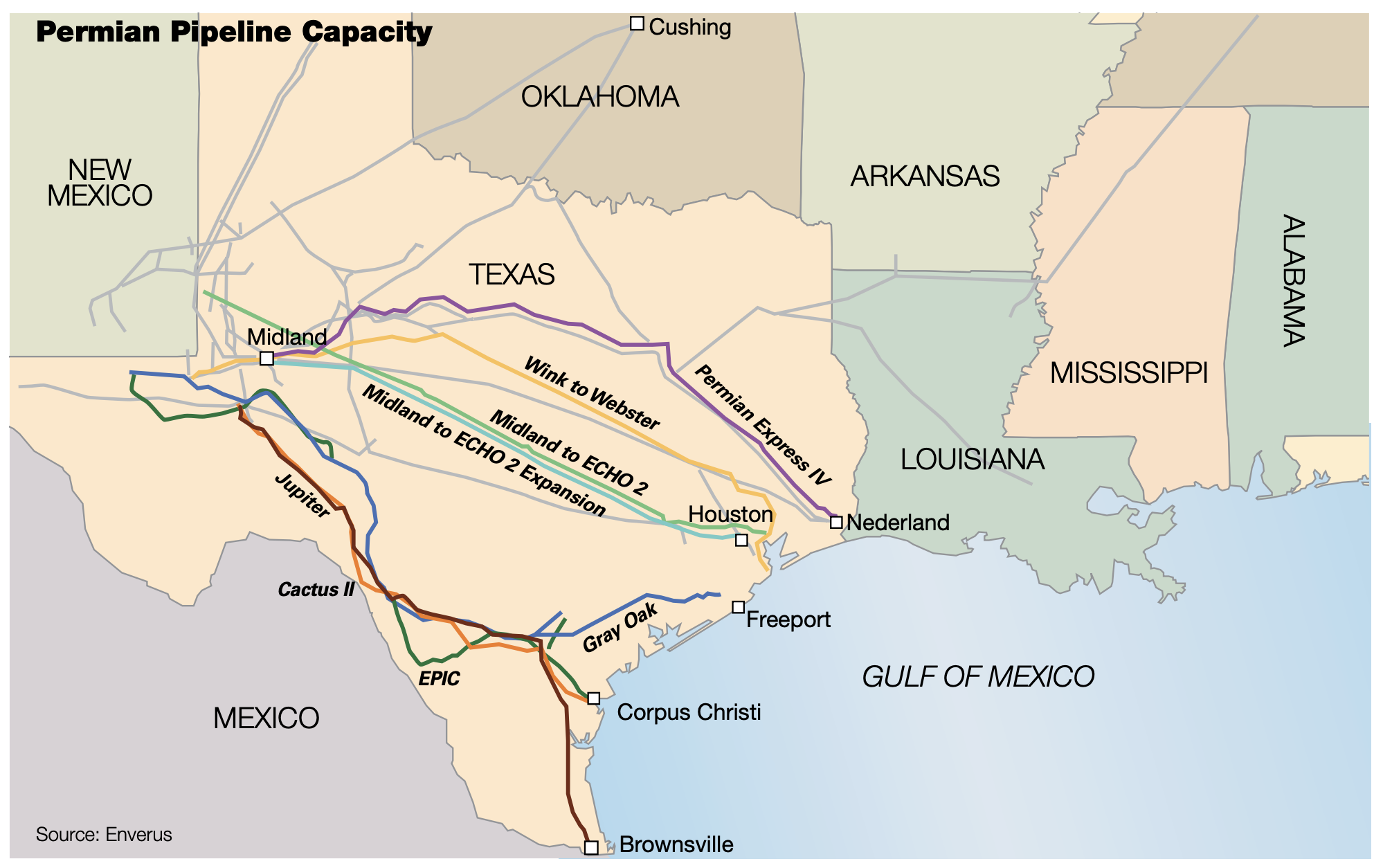

Much of the new wave of pipeline capacity is headed to Corpus Christi, Texas, and nearby areas as its primary destination. One such project is Cactus II, due to add 670,000 bbl/d of capacity in two stages, starting in the fourth quarter of this year and the first quarter of 2020. Backers are Plains All American Pipeline LP, Occidental Petroleum Corp. and physical commodity trader Trafigura.

Other projects include EPIC NGL, backed by Ares. With a capacity of 400,000 bbl/d, due to come online in the third quarter, the line is carrying crude for an initial period pending completion of a parallel crude line. As its name suggests, it will then carry NGL. Meanwhile, Gray Oak is scheduled to be in service by the end of this year with capacity of 900,000 bbl/d. Its principal sponsor is Phillips 66 Partners, which will operate the pipe.

Also notable is the mega Wink-to-Webster Pipeline, which is due to come online in the first half of 2021. Capacity is expected to be at least 1 MMbbl/d. Initial backers of the project include Exxon Mobil Corp. and Plains All American, who were recently joined by MPLX LP, Delek US Holdings Inc. and Rattler Midstream. The pipeline plans to serve the Houston area, including Webster and Baytown.

“What you have is a supply/demand imbalance—now you have too much pipeline,” commented Mercer. “The supply of pipeline space is greater than the demand for pipeline space. And just like in every other commodity market, under those circumstances we have a situation in which the price of pipeline space comes down, because you can effectively sell it, you can trade it.”

Try to mitigate sunk cost

In a market that is clearly oversupplied, terms to acquire pipeline space can quickly fall to far below a posted tariff—viewed as a “sunk cost” at that point—as shippers try to mitigate their losses, said Mercer.

“You can think about the differential between market hubs as being the implied free market value of pipeline space,” he said. “Shippers can’t monetize whatever unused space they have, so they’ll move incremental barrels at somewhere close to what their marginal cost to ship is. And that is not the initial tariff; it’s a handful of smaller items, including the ‘pipeline loss allowance.’”

The pipeline loss allowance is usually on the order of 20 cents to 30 cents/bbl at current crude prices. This very modest amount makes it easy for non-shipper third parties to take advantage of any spare capacity, provided the shipper—trying to mitigate its ‘sunk cost’ losses—can make enough margin to cover the pipeline loss allowance by buying the crude and then selling it back to third parties at its destination.

“That’s how you get to ‘convergence’ between market hubs,” explained Mercer. “If there is too much pipeline space, the economics quickly move to the marginal cost to ship. As long-haul takeaway capacity is added in the coming months, Midland differentials are likely to gain support [i.e., narrow],” he said. “And in a prolonged $50 to $55/bbl flat price environment, in-basin supply may not be enough for all committed shippers to fulfill their commitments. This is a recipe for tight differentials.”

Of course, the reverse imbalance can also exist, although the Permian Basin is not such a case today.

“When you have a different situation, in which you don’t have enough pipeline space, that space becomes very valuable. And it can be ‘sold’ by buying crude from a third party and selling it back to them at a much higher price at its destination,” said Mercer.

Full price difference

The initial Keystone Pipeline, for example, had anchor shippers that had 10-year take-or-pay contracts, he noted. “You would have done great over the past 10 years until production curtailments started in January of this year,” he explained. “Committed shippers captured the full price difference between Hardisty and Cushing.”

Matt Marshall is director, market analytics, with AEGIS Energy Risk LLC, headquartered in Houston. The company deals with some 150 upstream entities, spanning a variety of sizes and strategies. It has trading relationships with roughly 40 counterparties, mainly banks and a number of merchant traders, including subsidiaries of BP Plc, Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Cargill.

things we recently

flagged was that

the middle part

of 2020 was at

risk of becoming

much worse,” said

Matt Marshall,

director of market

analytics with

AEGIS Energy

Risk. “There’s a

lot of flared gas

in West Texas

that, once it has a

pipeline to carry

it, will probably be

collected rather

than flared.”

Marshall describes diffs, or basis, as a recurring issue, reflecting the fact that U.S. producers can respond to market signals much faster than a pipeline connecting markets can be built. Dealing with regulatory issues, filing for rights of way, ordering steel for the pipe, embarking on a marketing process, etc., all add up to “a much more complicated process” than building a pad and drilling wells.

“Rigs can typically be deployed within three months of a price signal. And production can either reverse a decline, or start to grow at a faster rate, some six to nine months after that price signal,” he observed. “The cycle time is much shorter than for a pipeline, which may take several years. And that leads to situations where there’s more supply than was expected.”

AEGIS works with clients to position them advantageously, if possible, ahead of such market imbalances.

“We help clients not just hedge their benchmark risk at Henry Hub, for example, but also help them to manage their locational risk in terms of basis,” said Marshall. As an example, he pointed to the gas basis blowout at the Waha Hub in West Texas last year.

“A lot of the weakness started happening in late 2017 and into early 2018, as more gas from Appalachia started to flow westward toward the Chicago market and beyond into the Gulf Coast market,” he recalled. “So there was just a lot more supply going into the Midwest in what had traditionally been a fairly large demand market.”

“It’s old news now. Producers are past that,” acknowledged Marshall. “But we issued early warnings about Midcontinent basis and about West Texas basis there at the end of 2017 and during 2018. And, of course, Waha ended up being a whole lot worse than the Midcontinent because gas production growth was really, really strong in West Texas.”

Waha forward curve improves

In term of hedging basis at Waha, the forward curve for West Texas basis at Waha currently “improves rapidly as you go into October and November of this year due to the Gulf Coast Express Pipeline coming into service early in the fourth quarter,” said Marshall. As you get into winter, the Waha forward price narrows considerably to a discount of near 60 cents off Henry Hub, he noted.

However, basis remains “elevated” for the summer of 2020, at about $1.30 off Henry Hub. As more pipeline capacity brings relief, the outlook and forward prices improve again in the winter of 2020 and 2021, according to Marshall.

“One of the things we recently flagged was that the middle part of 2020 was at risk of becoming much worse,” he said. “We know there’s a lot of flared gas in West Texas that, once it has a pipeline to carry it, will probably be collected rather than flared. We’ve observed in other basins, such as Appalachia, that when a pipeline comes online, there’s production waiting to make use of the new capacity.”

In addition, volatility in the daily, or cash, market in West Texas may be due to competing wind power.

“There’s quite a bit of wind power in West Texas that can affect the daily, or cash, market,” Marshall said. “If the wind is blowing, that wind will displace some of the demand for natural gas-fired power generation. And, therefore, on some days you’ll have dramatically less local demand to be able to absorb some of the gas.” However, hedging in the forward market tends to offer a greater degree of stability. “When you look into the forward months, what you’re doing there is calculating what you would expect to be an average of all 30 or 31 days in the month, and so there is less volatility and there are fewer of those really heavily discounted prices.”

As the winter of 2020 and 2021 approaches, the forward curve “improves rapidly,” observed Marshall. “Once you get past October of 2020, when the Permian Highway Pipeline by Kinder Morgan is due to be in service, Waha basis tightens up very strongly to close to a $0.65 discount to Henry Hub,” he said.

Of course, much of the West Texas gas projected to come online is headed to markets on the Gulf Coast. How will it change markets and basis, including these trends in the Haynesville?

Haynesville: Does demand measure up to supply?

“Haynesville basis isn’t going to be too much affected by West Texas gas flowing toward the Gulf Coast,” offered Marshall. “The reason is because the pipelines that connect the Haynesville to Henry Hub are north of Henry Hub, whereas the pipes that are affected by West Texas gas are to the west of Henry Hub. So, figuratively, they are on opposite sides of the fence.”

Instead, he continued, West Texas gas will become part of “a pool along the Texas Gulf Coast. And that pool will be dished out to whichever demand pays the highest price for it. It’s not like those molecules are earmarked for a specific location.”

However, the timing of the new gas supply—and even more so the timing of demand—will be critical.

“Is demand going to grow at the same rate as the new supply that will be flowing in from West Texas? That’s a legitimate question,” said Marshall. “It’s very possible that it will be mistimed such that the gas from West Texas arrives not at the same time as the demand. Depending on which one happens first, and in greater volumes, it could cause some increases in some basis values or decreases in basis values.”

“What we’re saying to our clients is that, if you have exposure to South Texas basis, you should look to protect yourself because there’s more downside risk if the supply comes faster than the demand,” he advised. “The upside is not as pronounced. Forward curves already reflect some of that risk.”

Recommended Reading

Halliburton’s Low-key M&A Strategy Remains Unchanged

2024-04-23 - Halliburton CEO Jeff Miller says expected organic growth generates more shareholder value than following consolidation trends, such as chief rival SLB’s plans to buy ChampionX.

CEO: Continental Adds Midland Basin Acreage, Explores Woodford, Barnett

2024-04-11 - Continental Resources is adding leases in Midland and Ector counties, Texas, as the private E&P hunts for drilling locations to explore. Continental is also testing deeper Barnett and Woodford intervals across its Permian footprint, CEO Doug Lawler said in an exclusive interview.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Americas

2024-04-23 - The final part of Hart Energy E&P’s Deepwater Roundup focuses on projects coming online in the Americas from 2023 until the end of the decade.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for Second Time in Three Weeks

2024-02-16 - Baker Hughes said U.S. oil rigs fell two to 497 this week, while gas rigs were unchanged at 121.

Sinopec Brings West Sichuan Gas Field Onstream

2024-03-14 - The 100 Bcm sour gas onshore field, West Sichuan Gas Field, is expected to produce 2 Bcm per year.