While the energy transition and ESG will force lots of assets to market, it also muddies the value proposition by increasing uncertainty around oil and gas valuations, the Wood Mackenzie analysts wrote. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

The pressure is rising for public companies to decarbonize. It’s bringing more upstream assets to the market—but also thinning the pool of traditional buyers. Will private equity fill the gap?

Private equity does have form in this market. Following the 2014/2015 downturn we saw a surge of entrants in places like the North Sea. While returns have been mixed, there’s speculation that private equity, less encumbered by public investors pushing for ESG progress, will see opportunities and surge into the sector once again.

Is that just speculation? Our research indicates that there is broad agreement that opportunities to invest are plentiful. In North America, for example, there is an opening for privately held operators to drill high-return acreage at a time when public companies are not increasing production, despite high prices.

There is early evidence of this playing out. In the Permian Basin, the percentage of wells drilled by private companies soared in 2021.

New private equity money seems to sense the opportunity. NGP and Pearl-backed Colgate made two Permian acquisitions last year. EnCap-backed Grayson Mill purchased Equinor’s Bakken position. Sabalo Energy II received a $300 million commitment from Encap to build an unconventional portfolio, and Warwick Investment Group is spending $450 million to buy and develop Eagle Ford assets.

And, of course, this isn’t just a North American story. International opportunities abound—but there are concerns.

While the energy transition and ESG will force lots of assets to market, it also muddies the value proposition. It increases uncertainty around oil and gas valuations, while new energies and associated industries offer a huge alternative investment opportunity.

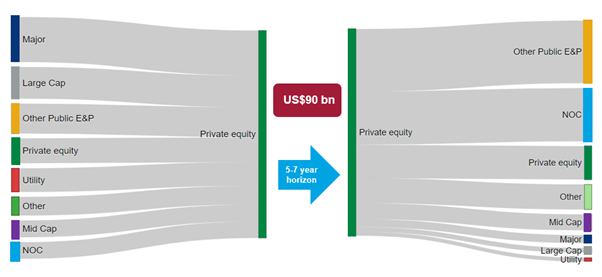

This creates a significant exit route issue. In the past, private equity has typically sold assets to three distinct peer groups: publicly listed E&Ps, NOCs and to other private equity. There are concerns over the future appetite of all three in this space. In short—the list of buyers willing to take on upstream assets is shrinking.

Plus, of course, ESG matters to private equity, and not solely because of exit routes. Some private equity funds are feeling direct ESG pressure from their ultimate owners—the limited partners. These backers often include institutions such as pension funds, many of whom increasingly have their own net-zero trajectories.

Opportunities may well abound, but private equity will be very selective in its choices and could drive a hard bargain.

For reward to outweigh risk, private equity will be looking for keen prices and cash-generative assets. Development projects don’t fit the bill. Marginally economic projects won’t satisfy requirements.

Historically successful oil and gas investors will continue allocating capital to good value opportunities. But new entrants, and investors who have struggled to generate adequate industry returns in the past, are unlikely to flood into the sector. For sellers looking to exit vast noncore positions, private equity buyers might be an option, but they’re unlikely to be a panacea.

Our conversations with private equity players identified quite a mixed response to the upstream opportunity. However, on balance we do think the industry is likely to move into a wider pool of private ownership. In the U.S., family-owned businesses such as Mewbourne and Endeavour have gained a significant foothold. While international examples are far fewer, the emergence of similar privately held structures seems inevitable.

About the authors: Greig Aitken serves as research director of M&A at Wood Mackenzie. Neivan Boroujerdi is principal analyst of North Sea upstream at the firm.

Recommended Reading

MethaneSAT: EDF’s Eye in the Sky Targets E&P Emissions

2024-03-07 - The Environmental Defense Fund and Harvard University recently launched MethaneSAT, a satellite tracking methane emissions. The project’s primary target: oil and gas operators.

Exclusive: Scepter CEO: Methane Emissions Detection Saves on Cost

2024-04-08 - Methane emissions detection saves on cost and "can pay for itself," Scepter CEO Phillip Father says in this Hart Energy exclusive interview.

Fire Closes Atlas Energy’s Kermit, Texas Mining Facility

2024-04-15 - Atlas Energy Solutions said no injuries were reported and the closing of the mine would not affect services to the company’s Permian Basin customers.

Darbonne: ESG, ‘Oh So 2022,’ Reduced to Table Stakes?

2024-02-11 - ESG champion BlackRock is paring, while Exxon Mobil’s growing. Today, ESG is just table stakes.

SAF End-users, Producers Talk Challenges, Solutions

2024-02-07 - The lower lifecycle emissions of sustainable aviation fuel are seen as a key lever for airlines to reduce carbon emissions, but cost is a challenge.