So why does the U.S. import crude and petroleum products from Russia? According to a fact sheet released last week by the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers, it comes down to logistics, Hendrickson says. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

This is an excerpt from the Ralph E. Davis Associates (RED) Weekly E&P Update Newsletter.

Over the weekend, I saw a comment (a tweet, actually) by a politician conflating our imports of oil from Russia with the Keystone XL pipeline. He claimed that if Keystone was approved, we wouldn’t import any crude from Russia. This struck me as a big oversimplification, so I decided to look a bit closer at why we import oil from Russia in the first place.

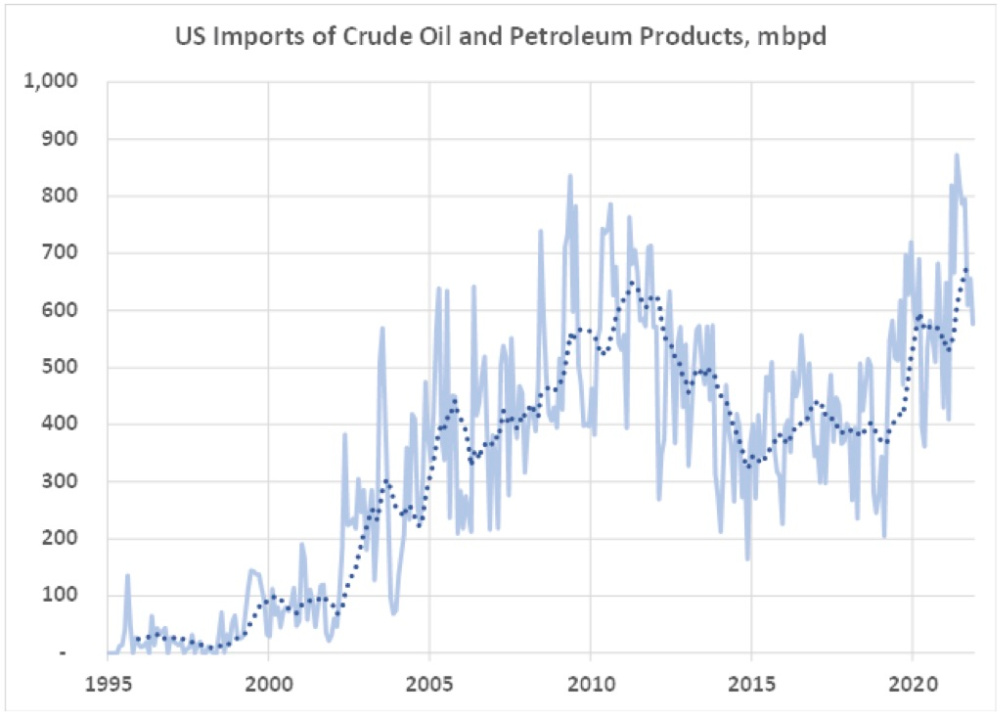

The graph below shows historical crude oil and petroleum products imports into the U.S. from Russia in thousands of barrels per day as reported by the Energy Information Administration (EIA). I’ve added a 12-month moving average, as well. According to the EIA in the most recent months they’ve reported, about 70% of these volumes are petroleum products, most of which are partially refined crude (unfinished oils) or motor gasoline. Unfinished crude that’s further refined into gasoline once it reaches our shores makes up about half of our petroleum imports from Russia. Altogether, these volumes account for about 3% of the U.S.’s daily petroleum consumption of approximately 18.2 million bbl/d (EIA, 2020)—as an interesting aside, this pandemic-depressed volume was the lowest level of petroleum consumption in the U.S. since 1995.

So why do we import crude and petroleum products from Russia? According to a fact sheet released last week by the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), it comes down to logistics. The crude oil and unfinished oil portion of these imports go mostly to the West Coast. Refineries there primarily use light sweet crude as their feedstock and there are limited supplies available to this market. Gulf Coast refineries tend to be designed for heavier, often higher sulfur crudes, from places like Venezuela and Mexico.

The smaller gasoline portion of Russian imports goes to the East Coast market, which lacks sufficient local refining capacity to meet its needs. And a lack of infrastructure makes it difficult to supply these markets by transporting gasoline from Gulf Coast refining centers.

Given our country’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it seems likely that we’ll lose these volumes from our market. According to AFPM, other countries such as Canada and Latin America should be able to make up for this shortfall. However, the rest of the world will likely experience significant oil supply disruptions as Russia is isolated from the global economy. In the near term, this will certainly lead to higher oil and gasoline prices for everyone.

Last week, I discussed how the U.S. oil-directed rig count wasn’t responding as strongly as I would expect given the response observed during the previous two price spikes. It seems to me that if there was ever a time during my career for U.S. producers to rise to the challenge and increase domestic production, this is it.

About the Author:

Steve Hendrickson is the president of Ralph E. Davis Associates, an Opportune LLP company. Hendrickson has over 30 years of professional leadership experience in the energy industry with a proven track record of adding value through acquisitions, development and operations. In addition, he possesses extensive knowledge of petroleum economics, energy finance, reserves reporting and data management, and has deep expertise in reservoir engineering, production engineering and technical evaluations. Hendrickson is a licensed professional engineer in the state of Texas and holds an M.S. in Finance from the University of Houston and a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from The University of Texas at Austin. He recently served as a board member of the Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers and is a registered FINRA representative.

Recommended Reading

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Americas

2024-04-23 - The final part of Hart Energy E&P’s Deepwater Roundup focuses on projects coming online in the Americas from 2023 until the end of the decade.

E&P Highlights: April 1, 2024

2024-04-01 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including new contract awards.

Remotely Controlled Well Completion Carried Out at SNEPCo’s Bonga Field

2024-02-27 - Optime Subsea, which supplied the operation’s remotely operated controls system, says its technology reduces equipment from transportation lists and reduces operation time.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Offshore Australasia, Surrounding Areas

2024-04-09 - Projects in Australia and Asia are progressing in part two of Hart Energy's 2024 Deepwater Roundup. Deepwater projects in Vietnam and Australia look to yield high reserves, while a project offshore Malaysia looks to will be developed by an solar panel powered FPSO.

E&P Highlights: March 15, 2024

2024-03-15 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a new discovery and offshore contract awards.