As the energy sector shifts toward a more sustainable future, the expectations thrust upon in it are, in a sense, outpacing innovation.

After all, while oil and gas leaders are expected to target carbon-neutral operations, the technology does not yet exist that would allow them to operate in a net-zero fashion. It means out-of-the-box thinking—and the strategic use of carbon credits and offsets—is necessary for those seeking an equilibrium between operations and environmental responsibility.

Mitigation is nothing new in the energy sector, where companies have for decades been using carbon capture in their EOR operations, pumping CO₂ into the ground as the oil and gas is pumped out.

But during a time of growing regulatory and investor demand for clean energy, companies are increasingly turning to carbon credits, capture and offsets to help shape their overall operational strategies. They’re both exploring how to source from low-carbon vendors to ensure an emissions reduction, and trying to otherwise compensate for those greenhouse gasses.

“Connecting carbon sequestered with carbon emitters, through offsets is going to be a really important way that we deal with the climate. There’s going to be no other way to go about it.” — Rachel Schelble, Head of Wood Mackenzie’s Carbon Management and Infrastructure Research

“We see the voluntary carbon market really expanding very significantly in the next few years,” said Elena Belletti, Wood Mackenzie’s head of carbon research. “As we see governments around the world—and states throughout the U.S.—make more and more ambitious pledges, one can only expect that there will be more measures taking place that would require companies to reduce their carbon emissions or attach a credit to that.”

Multibillion-dollar market

Since 2019, voluntary carbon offset volumes have tripled with the market expected to reach more than $200 billion by 2050, according to a Wood Mackenzie report. It means developing low-carbon strategies are crucial for companies seeking to have a competitive advantage during a time when investors are demanding low-carbon footprints.

“Corporate carbon management plans must adhere to an order of emission-reducing operations, with a first step focused on avoiding emissions through operational improvements,” according to the February report on carbon offset insights. “How companies source and use carbon offsets will be critical.”

Within the energy industry, steps include evaluating carbon offset needs, sourcing offsets and using them. Good carbon management strategies, the report stated, involve diversifying the sources of offsets to include them as both a decarbonization mechanism and a financial tool.

“Carbon offsets are a key tool in providing flexibility in corporate carbon management plans, as long as they are used only for hard-to-abate emissions in the long run. The carbon market will continue to evolve rapidly, and today’s carbon offset business models will need to allow for strategic corrections. With the price of carbon offsets expected to significantly rise over the coming years, companies must develop these corporate strategies now.”

Of course, there’s a limit to the amount of carbon offsets that are considered good practice in the energy industry. The net-zero standard allows for 50% of total emissions to be compensated with offsets or sequestration, which is considered high in comparison to other industries to reflect the difficulty to abate emissions with operational changes.

Carbon capture

When it comes to carbon sequestration, there’s a spectrum of costs associated with technologies and approaches, ranging from direct air capture to nature-based solutions. Perhaps not surprisingly, natural solutions are considered to be among the least expensive ways to sequester carbon and achieve offsets.

“When you see this wide range of technologies, and the costs associated with them, there’s different plans and strategies between all the companies to push each one of these forward,” said Rachel Schelble, who heads Wood Mackenzie’s carbon management and infrastructure research. “And on the offsets side, because implementing nature-based solutions is much cheaper than some other technologies, that's what a lot of the focus has been on for a lot of the corporate majors.”

Nature-based solutions can include sequestration in the environment—including in soil and mangroves—to capture carbon into plant matter. They can also create their own offsets through mass tree planting, establishing wetlands, and otherwise contributing to conservation efforts that bolster carbon storage.

RELATED:

Where’s the Value in Carbon Management?

Oil Industry Emerges as Leader in Global Carbon Management Efforts

While most companies are participating in carbon capture voluntarily, there are also critical financial incentives for doing so. In today’s market, the investment capacity of corporations is linked to sustainability, meaning whether they’ll be financially backed in the future is tied to the practices they’re putting in place now to become more environmentally responsible.

Fortunately for the oil and gas sector, corporate leadership is in a good position to meet the challenge.

“If you look at the oil and gas industry, they—because of the subsurface knowledge that they have and the deep technical understanding of the earth—there’s a lot that they can bring to bear on the topic,” Schelble said. “And so there’s an expectation from investors that they are going to bring that to the topic and move us forward in that direction.”

Credit criticism

Carbon offsets and credits have been—and continue to be—a sore spot for critics, who consider them to be a sneaky workaround enabling oil and gas companies to operate irresponsibly. But the reality is, they can be a useful and effective tool if used for their intended purpose of mitigating emissions, researchers say.

Reputable companies use them as part of a larger solution in conjunction with other measures intended to minimize environmental impact.

“This is actually a very effective instrument to reduce global carbon emissions,” Belletti said. “In the end, I think it’s everybody's aim to avoid the catastrophic effects of climate change. And in reality, from an empirical point of view, what we can observe is also usually companies that do have carbon offsets built into their strategy have them because they have a strategy in place. They already have a way to achieve net-zero emissions and then they have taken offsets as part of that.”

Researchers aren’t observing companies purchasing mass amounts of carbon offsets without doing anything else to reduce emissions. From a reputational standpoint, doing so would be a poor strategy, Belletti said.

“Many countries are either putting a price on carbon or developing appealing carbon markets to incentivize carbon capture.” — Mora Fernández Jurado, Energy Transition Research Associate at Darcy Partners

Her colleague Schelble agreed, noting that there’s an order of emissions reduction that companies must follow to be considered responsible operators.

“Connecting carbon sequestered with carbon emitters, through offsets is going to be a really important way that we deal with the climate,” she said. “There’s going to be no other way to go about it. Companies that actually have a strategy are not greenwashing. They're developing a strategy for how to mitigate this.”

Most offsets within the voluntary carbon market are often verified by established third parties, which helps eliminate public mistrust, said Mora Fernández Jurado, an energy transition research associate at Darcy Partners.

They also produce an income for corporations and individuals—including farmers—who reduce carbon levels within the atmosphere and can play a significant role in combating climate change.

“The system ultimately incentivizes people to plant more trees in their lands or to choose natured-based solutions in exchange for any engineered solution,” Fernández Jurado said. “And the higher the carbon value, the bigger the incentive. At a certain point, it might be more profitable to farm using regenerative agriculture than conventional one.

“So, all in all, I believe this is an effective measure for the mitigation of climate change, because it turns what used to be a liability [CO₂] into an asset that people can profit from. Taking care of the environment now will be an advantage for people, and it really doesn't matter if they believe in the energy transition or not.”

Growing momentum

EOR—the process of increasing well flow through the injection of water, chemical or gasses—has been used as the original carbon capture solution since the 1970s. The Terrell Natural Gas Processing Plant was among the first companies utilizing EOR and captures between 400,000 and 500,000 tons per year in the process, according to the Colorado School of Mines.

The technique has become more popular in today’s world and is commonly used as a way to displace emissions while continuing the extraction of fossil fuels from existing wells.

Environmental incentives for transitioning toward carbon capture and storage began growing with the Kyoto Protocol and subsequent U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change meetings, said Fernández Jurado.

Other factors driving an international commitment to reduce emissions include stakeholder impact and carbon pricing, she said.

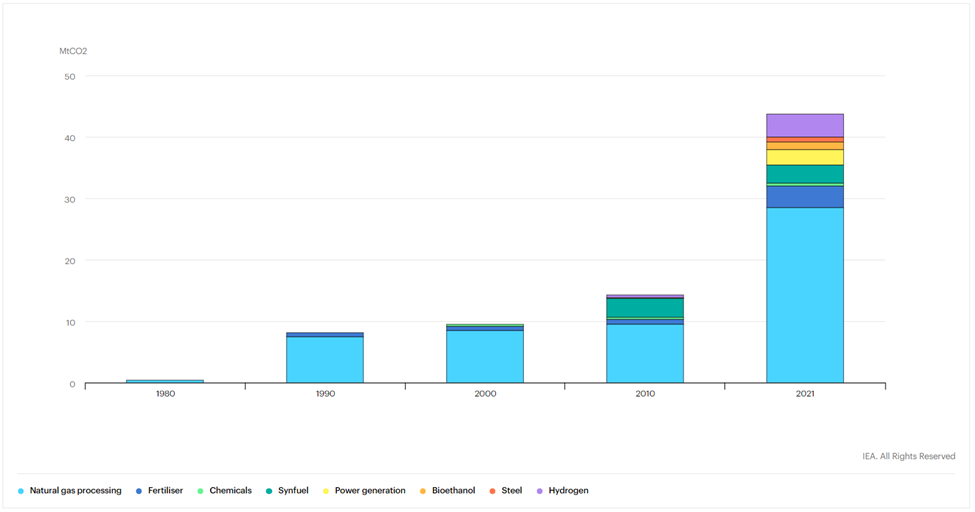

“Many countries are either putting a price on carbon or developing appealing carbon markets to incentivize carbon capture,” Fernández Jurado said. “We can see that a strong embrace has started around 2010 with an impressive growth in the last couple of years.”

According to the Global CCS Institute, the number of carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects grew 28% from December 2020 to September 2021. Despite the “unprecedented” growth, a “massive gap” remains between today’s figures and the additional reductions necessary to achieve net-zero emissions, the institute said.

The challenge? Upward of $1.28 trillion in capital investment is needed by 2050 to increase CCS capacity from about 40 MPta today to more than 5,600 MPr by 2050.

For instance, according to the Global CCS Institute, the number of projects grew by about 50% between December 2020 and September 2021.

“The figure might appear daunting, but investing around $1trillion over almost 30 years is well within the capacity of the private sector,” the institute said in a report. “In addition to enormous financial resources, the private sector has the expertise and experience to develop projects. In the face of rising expectations from stakeholders and shareholders to invest in assets that aid climate mitigation, the private sector is also actively seeking opportunities. All that’s needed is a business case.”

Challenges abound

Despite the technological advancements made amid decades of CCS, capturing carbon remains both expensive and inefficient, Fernández Jurado said.

“The amount of money being dedicated to CCS does not yet meet the level of deployment needed,” she said. “There are many technologies that still need to be tested in the field to be then corrected and retested. This requires a lot of money in investments that also come in with higher risks.”

As well, some companies are reluctant to invest in the best available technology since there’s little value in the CSS process, she added.

“Carbon capture rarely brings about money for the big emitters and therefore, their desire to spend money on better technology is greatly reduced,” Fernández Jurado said. “This is also why EOR was the initial CCUS solution. Because there was some profit for the companies. In this space, there’s an increasing number of innovators (or technology developers) looking at carbon utilization to valorize carbon dioxide or at developing carbon markets to trade offsets.”

But within the energy sector, companies that don’t join the carbon capture and offset movement could ultimately face higher upfront costs and lose investors.

“I’m quite sure that at a certain point, it will be clear that they will be reducing their earnings due to the carbon impact of their businesses,” Fernández Jurado said. “They will also lose public image and environment-aware clients will shift to cleaner companies.”

Recommended Reading

Enbridge Sells Off NGL Pipeline, Assets to Pembina for $2.9B

2024-04-01 - With its deal to buy Enbridge’s NGL assets closed, Canada's Pembina Pipeline raised EBITDA guidance for 2024.

Pembina Pipeline Enters Ethane-Supply Agreement, Slow Walks LNG Project

2024-02-26 - Canadian midstream company Pembina Pipeline also said it would hold off on new LNG terminal decision in a fourth quarter earnings call.

Enbridge Announces $500MM Investment in Gulf Coast Facilities

2024-03-06 - Enbridge’s 2024 budget will go primarily towards crude export and storage, advancing plans that see continued growth in power generated by natural gas.

Summit Midstream Sells Utica Interests to MPLX for $625MM

2024-03-22 - Summit Midstream is selling Utica assets to MPLX, which include a natural gas and condensate pipeline network and storage.

Pembina Declares Series of Quarterly Dividends

2024-04-10 - Pembina Pipeline Corp’s board of directors declared quarterly dividends for series 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 15, 17, 19, 21, 22 and 25.