As West Texas Intermediate prices creep toward $70 per barrel, some companies may be tempted to abandon capital discipline for crude plunder. But E&Ps are already showing restraint, while Permian players face a midstream bottleneck.

For much of his 35-year career, Chaparral Energy Inc. CEO Earl Reynolds saw a plain, clear strategy for oil and gas companies.

The industry ran from one big discovery—sometimes onshore, sometimes offshore or through the extraction of coalbed methane—to the next. But always, companies ran and spent.

“At the end of the day, the overall strategy was to chase the resource,” he said.

In those days, E&Ps sought new resources to grow, which required reinvesting capital.

Then the curtain fell, and a new backdrop of zones, stages, proppant and sweet spots grew up around the unconventional drilling revolution. For some companies, resources are now in place for five, 10 or even 20 years of drilling.

“Supply is not a question today,” Reynolds said.

Instead, he said, it’s about which company can execute the best.

Investors have increasingly distanced themselves from oil and gas companies—and more broadly the energy sector—as they hunt for returns. That’s put pressure on producers to rapidly triage the challenges of overspending, high levels of debt and unneeded acreage.

But other factors beginning to emerge suggest that just one course correction by companies, such as throttling back spending or hacking at debt, may not be enough to lure investors back.

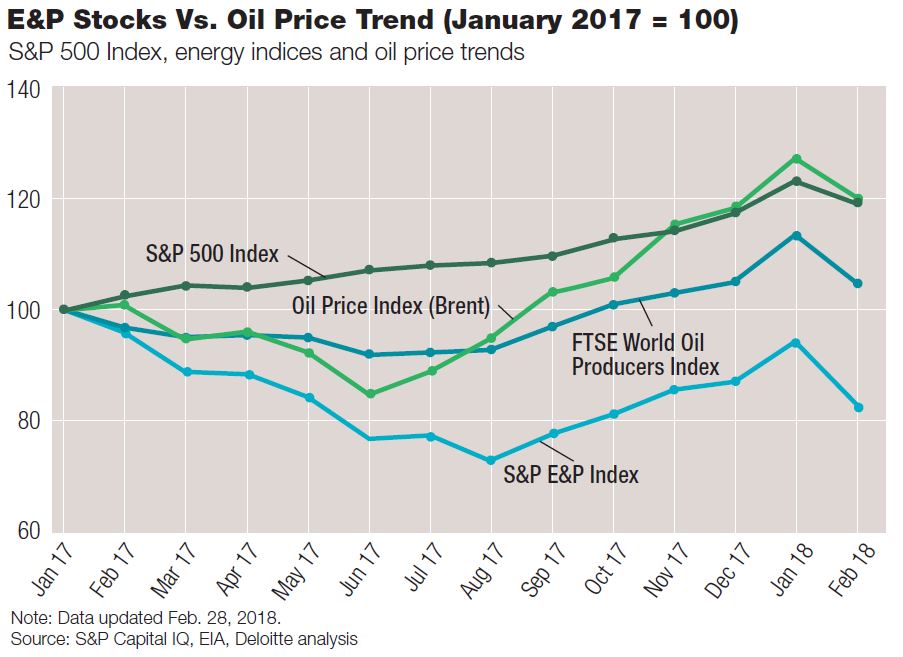

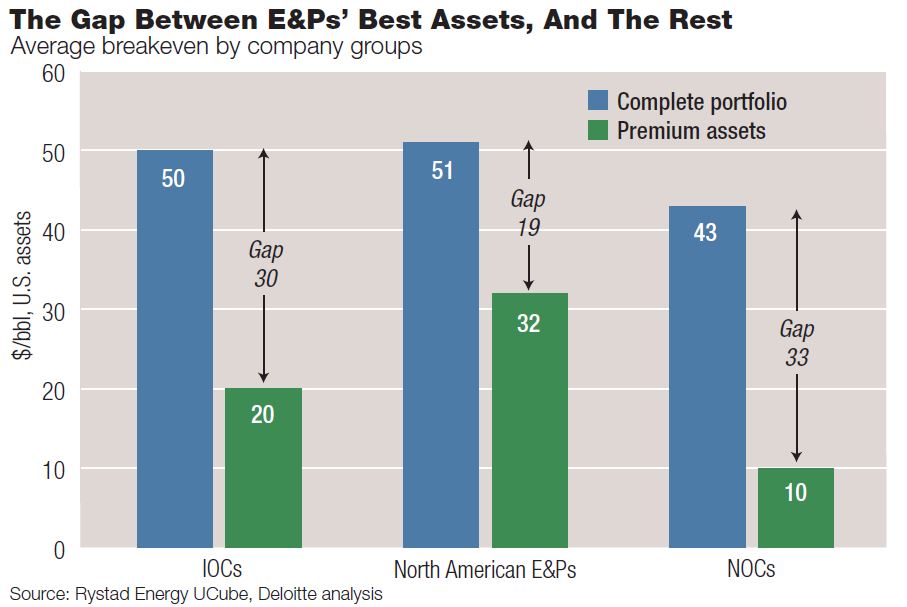

Since January 2017, oil prices have recovered by about 25%. However, 73% of global E&Ps haven’t seen a corresponding rise in stock prices. Even companies in marquee regions such as the Permian Basin have seen their share prices wither by14% despite the rise of crude prices, according to an April report by Deloitte.

Investor apathy can be blamed on a number of factors. For one, upstream companies are still struggling with shaky finances. More than three out of four of global upstream companies would begin to buckle at $55 per barrel oil prices. Under those conditions, they will face difficulty sustaining production, funding future growth and continuing shareholder payouts over the next five year.

“People want some consistency and repeatability,” Andrew Slaughter, executive director for Deloitte’s Center for Energy Solutions, told Investor. “That’s one of the reasons why we think there’s an undervaluation. There’s confusion about the real performance of the sector and the relative performance of companies.”

Capex and leverage are clearly integral to restoring E&Ps to their former glory. But they’re not the only factors.

Reynolds believes some investors have fled to what he calls FANG stocks—a reference not to Diamondback Energy Inc.’s ticker symbol, but to Facebook, Apple, Netflix and Google.

“A lot of the general investors have left the E&P space and entered these technology stocks,” he said. “Until those investors see a compelling reason to return, the industry will be forced to be disciplined, which, I think, is a good thing.”

By many measures, consolidation, efficiency and a strong, straightforward story will be essential to E&Ps recapturing market share.

“The lowest cost operator is the company that ultimately survives and thrives in this type of cycle,” Reynolds said. “That’s why we’ve focused so heavily on maintaining a low-cost structure and capturing efficiency gains where we can as we’ve made the transition to a pure-play Stack company.”

Zone dieting

In February, the leaders of Sanchez Energy Corp., Oasis Petroleum Inc. and Alta Mesa Resources Inc. were asked whether they would alter spending if West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices began to rise.

At Hart Energy’s DUG Executive conference, CEO Tony Sanchez III, Alta Mesa’s Hal Chappelle and Oasis President Taylor Reid responded that they didn’t foresee plans changing because the long-term price was more important than monthly variance.

Reynolds is of the same mindset.

“We try to design our budget around a plan that is predicated on roughly the strip at the time,” he said. “We of course have our own view of what we think the commodity is going to do, but we design the company to operate efficiently and return value in a $40 and $60 world.”

Reynolds noted that oil remains in a backwardation curve, with prices out through 2022 still in the low $50s.

Chaparral’s strategy to take advantage of high prices but guard against painful low points mirrors what Deloitte’s analysis sees as differentiating top global upstream companies from the rest of the pack.

Slaughter said E&Ps should continue to “future proof” their companies either to take advantage of rising prices or shield themselves from downside prices of $40. Most of the top companies examined by Deloitte followed a consistent strategy, whether it was concentrating portfolios or diversifying them.

“With strip prices rising to as high as $68 per barrel of WTI, there’s more opportunity for E&Ps to reinvest cash flow back into core positions and start to grow production again,” he said. “The key is to do that in a more financially disciplined approach, not over levered and in a way that the market goes crazy like it did last time.”

Successful companies have also largely refrained from moving into trending basins, instead focusing on one region to master it.

For all of its strides, the upstream sector remains vulnerable to low commodity prices and loads of debt.

Many E&Ps are anchored to years of debt accumulated through chasing resources during the land grabs of the past five or six years.

“As soon as the oil price turned in late 2014 and later collapsed, those companies were really exposed and basically struggling to service debt from their existing ongoing operations,” Slaughter said.

Most of the companies Deloitte grouped as the “top 30 operators” have a moderate, but disciplined net debt to capital ratio of 25% to 55%.

Despite sitting on a record pile of debt, about 70% of global upstream companies reported profits or positive free cash flow in fourth-quarter 2017, Deloitte reported.

Nevertheless, high leverage remains a widespread problem.

“Many E&Ps are not out of the woods,” he said. “There’s still lot of debt.”

No more levers

As E&Ps begin to breathe easier in a climate of WTI prices of $65 per barrel or more, will any fall to the temptation to up capex and produce more for greater returns?

For some basins, the Permian in particular, jacking up production seems impractical. E&Ps also have a shaky history of committing to capital discipline. Like Mark Twain said of smoking, it’s easy: “I’ve done it a thousand times.”

But skepticism seems to be fading. Companies are using portfolio rationalization to improve their profiles among investors. In some cases, cash flows and asset sales are being used to buy back stocks.

“Thematically, it’s them getting more discipline,” said Brook Papau, managing director at RS Energy. “Some of these sales are companies high-grading into their most capital efficient assets. In line with that they’re signaling to the market that they are going to be capital disciplined.”

Generally, Papau said, the oil and gas industry’s capital restraint is the new normal. Companies such as QEP Resources Inc. and Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. have said they would return capital to shareholders. QEP said it planned to repurchase $1.25 billion in shares. In March and April, the company bought back about $60 million in shares. Cabot similarly has enacted buybacks and paid dividends totaling $234.8 million as it follows through on a program to buy back 30 million shares, the company said in late April.

“It’s not a trend I expect to reverse any time soon,” he said. “Maybe we’ll see marginal cost inflation, but I don’t think we’re going to see the days of five to eight years ago.”

Even with WTI rising $10, its more likely that companies would look to buy back shares or start announcing dividends.

Even Permian players, with some 25 years of inventory runway, may see no reason to increase the rate of production growth, largely due to physical and financial barriers. Tightening takeaway capacity in the Permian has choked off oil exports via pipeline from the Midland and Delaware basins, leaving trucking crude as the only and more expensive option. In April, producers faced differentials of above $10 per barrel (bbl). Papau said by the end of 2018, differentials may rise to $15/bbl.

“There really isn’t a lever to production growth by adding more rigs in the short term,” he said, adding that there’s not an easy method for oil to be inexpensively transported

The Permian’s pipeline woes, which should start to ease in 2019, add to a bullish outlook on WTI pricing.

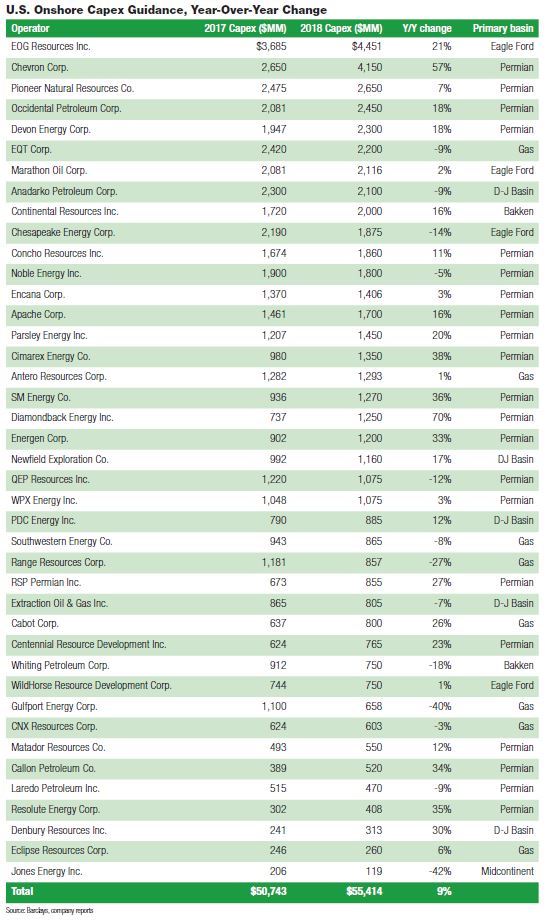

Overall, E&Ps have surprised industry watchers with their initial 2018 capex guidance. Barclays’ December forecast predicted North American E&P spending would increase by about 21%.

Instead, as further spending guidance emerged, the top 40 producers as identified by Barclays—accounting for more than 50% of U.S. onshore production—had only modestly upped spending. Capex increased by about 9% compared to 2017.

Of the top 40 companies, 12 reduced capex, including three Permian pure-play companies.

“Although we have often heard E&Ps proclaim they will spend within cash flow, preliminary 2018 budgets show E&Ps really mean it and are listening to the loud chorus of investors demanding capital discipline and higher returns,” J. David Anderson, a Barclays analyst, said in an April report.

Papau said that operators are now faced with searching for improvements in efficiency while protecting against inflationary pressures.

E&Ps should be more focused on execution, particularly in the Permian. The days of riskier land grabs and the uncertainty of whether the assets would pan out has given way to E&Ps realigning their priorities.

“They’re in a different mode now where these companies have to behave like long-term going concerns,” he said.

Reynolds, though, shared one lesson he learned early on in his oil and gas career.

“You never say never in this business,” he said.

Recommended Reading

APA Corp. Declares Cash Dividend

2024-02-12 - At a rate of $0.25 per share, APA’s dividend is payable May 22 to stockholders of record by April 22.

APA Shuffles Leadership Following Callon Acquisition

2024-04-09 - APA CEO John J. Christmann said the changes will structure leadership to better align with the company’s “evolving” business needs.

CEO: Coterra ‘Deeply Curious’ on M&A Amid E&P Consolidation Wave

2024-02-26 - Coterra Energy has yet to get in on the large-scale M&A wave sweeping across the Lower 48—but CEO Tom Jorden said Coterra is keeping an eye on acquisition opportunities.

E&P Earnings Season Proves Up Stronger Efficiencies, Profits

2024-04-04 - The 2024 outlook for E&Ps largely surprises to the upside with conservative budgets and steady volumes.

Petrie Partners: A Small Wonder

2024-02-01 - Petrie Partners may not be the biggest or flashiest investment bank on the block, but after over two decades, its executives have been around the block more than most.