(Source: happyphotons/Shutterstock.com)

The U.S. benchmark Henry Hub price of natural gas will be less relevant in the next phase of the global LNG business model, Tellurian Inc. CEO Meg Gentle said during the recent North American Gas Forum, organized by Energy Dialogues LLC.

That’s because partners up and down the value chain will work together to achieve supply and price certainty, she said.

“The price at Henry Hub is actually set by the most expensive molecule of natural gas in the U.S. because that’s what it takes to clear the market,” Gentle said. Integrating the value chain involves working with a known price of gas.

It Takes a Village, er, Value Chain

Tellurian’s model for its Driftwood LNG facility, to be built on the Calcasieu River, south of Lake Charles, La., involves partnering with a producer in the Haynesville gas play and developing a 96-mile pipeline to deliver an average of 4 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) to the facility. The $15.5 billion project will boast a capacity of 27.6 million tonnes per year when complete. Construction is slated to begin in 2021.

“As we produce the gas at the wellhead and bring it all the way into the market, the relative value in the different parts of the value chain are changing over time, and so the best value that comes from the project—that comes from the partners—is participation together and aligned on all those pieces,” she said.

“The cost of producing gas in the Haynesville has very little volatility,” she said. “It’s really that cost certainty that we bring to the market from integrating the project, that we know we have LNG delivered at $5 or less, depending on how far we’re taking it.”

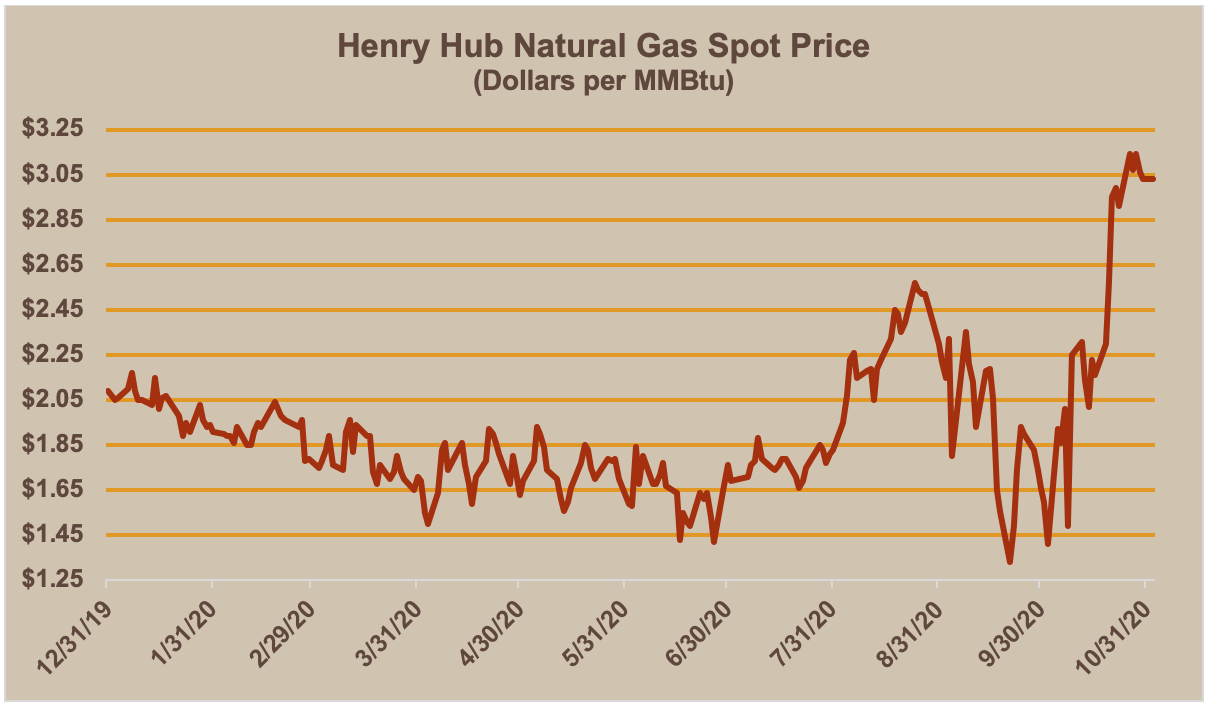

The actual production price for Driftwood’s gas in the Haynesville is about $1.50/MMBtu, Gentle said. By contrast, the Henry Hub price on the afternoon of Nov. 10 was $2.95/MMBtu. It costs about $2/MMBtu to deliver the gas from the wellhead in the Haynesville to the plant.

“With upward pressure on Henry Hub,” she said, “we’re really focused on making sure we can deliver really low-cost LNG to the partners by doing the project on an integrated basis and making sure that we’re loading LNG on the Gulf Coast at roughly $3.50 and delivering in Asia at $5/MMBtu.”

The price for Asian gas on the benchmark Japan Korea Mark (JKM) was $6.905/MMBtu on Nov. 10. In Europe, the Nov. 10 price on the Title Transfer Facility (TTF) in the Netherlands was $4.868/MMBtu.

The ‘Homeless’ Problem

Globally, many LNG projects of 10-12 years ago were developed with the intent of serving the pre-shale U.S. market, said Majed Limam, manager of Americas for Poten & Partners, an energy and shipping brokerage. When the demand market morphed into a supply market, a lot of LNG supply in the Atlantic Basin became “homeless.”

“That disrupted the old-fashioned approach in LNG where demand would develop and supply would catch up and you’d have a nice step function where demand and supply would meet nicely,” Limam said during the forum. “There was, all of a sudden, that surplus LNG.”

As the market shifted, the LNG business did, too. Driftwood represents the fourth evolution of U.S. LNG, Gentle said. The path from point-to-point contracts serving the Japanese market has matured into today’s fully traded, liquid commodity.

“Some of the big milestone changes, when you think of them, you can match them with the evolution in how projects begin, where the capital comes from and how we became more and more flexible,” she said. The milestones are:

- Atlantic LNG of Trinidad and Tobago offering the first LNG traded in the Atlantic Basin that was not point to point;

- BP Plc creating a liquid portfolio, which led other portfolio companies to join and bring liquidity to the market; and

- Cheniere Energy Inc., where Gentle worked prior to Tellurian, converting the Sabine Pass, La., import terminal into an export terminal, which was the birth of U.S. LNG. The business model introduced flexibility to the sector with no destination restrictions.

Recovery Ahead

2020 has been a less-than-stellar year all around in the fossil fuel space, but LNG has made it through in decent shape.

“The signs are for a recovery,” Limam said. “If you look at how the LNG industry and the market performed compared to oil and other commodities worldwide, it’s held its own. We may not see the growth that was anticipated for 2020 in 2019, but we’re not going to see a very large drop.”

And if growth was modest this year, it is expected to pick up again in 2021 and the medium- to long-term looks promising for LNG, Limam said. A key difficulty earlier in 2020 was the inability of Europe to absorb the surplus LNG in the Atlantic Basin, but that issue is in the past.

“The price arbitrage has opened up now,” he said. “Where the Asia Pacific prices are, it’s definitely promoting trade from the U.S. and other parts of the Atlantic into these markets.”

By mid-decade, the market will catch up to the surplus and resolve the “homeless” LNG problem.

“The silver lining is that we see a tightening of the market now happening sooner, perhaps in a decade, because of the delays on some [final investment decisions],” Limam said. “The projects that do make it and are operational by that time frame, perhaps have a better opportunity now than they did before.”

Recommended Reading

US Interior Department Releases Offshore Wind Lease Schedule

2024-04-24 - The U.S. Interior Department’s schedule includes up to a dozen lease sales through 2028 for offshore wind, compared to three for oil and gas lease sales through 2029.

Utah’s Ute Tribe Demands FTC Allow XCL-Altamont Deal

2024-04-24 - More than 90% of the Utah Ute tribe’s income is from energy development on its 4.5-million-acre reservation and the tribe says XCL Resources’ bid to buy Altamont Energy shouldn’t be blocked.

Mexico Presidential Hopeful Sheinbaum Emphasizes Energy Sovereignty

2024-04-24 - Claudia Sheinbaum, vying to becoming Mexico’s next president this summer, says she isn’t in favor of an absolute privatization of the energy sector but she isn’t against private investments either.

Venture Global Gets FERC Nod to Process Gas for LNG

2024-04-23 - Venture Global’s massive export terminal will change natural gas flows across the Gulf of Mexico but its Plaquemines LNG export terminal may still be years away from delivering LNG to long-term customers.

US EPA Expected to Drop Hydrogen from Power Plant Rule, Sources Say

2024-04-22 - The move reflects skepticism within the U.S. government that the technology will develop quickly enough to become a significant tool to decarbonize the electricity industry.