(Source: Kelly Oil & Gas LLC)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the May 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Until 2000, the Williston Basin’s Bakken Formation had been a bailout zone. When a well targeting another formation wasn’t going to pay, the Bakken was tapped for what little the super-tight rock would give up. The investors might recoup some of what they spent.

Burlington Resources Inc. had tried tapping the formation with horizontals in the late 1980s and into the early 1990s. It had some initial indication of success in a sweet spot in western North Dakota.

But it had been landing the laterals in the upper Bakken—a shale member—and hadn’t been fracking them. The wells dried up fast while trying to move oil out of nearly solid rock. The play was declared dead in a 1996 report by the North Dakota Geological Survey.

“Without a change in current circumstances,” it reported, “such as a new way to stimulate Bakken Formation reservoirs or the discovery of a new area with rock and/or reservoir properties similar to the (productive) fairway, completions in the Bakken Formation will be made only for salvage ....

“There will always be a few completions in the Bakken Formation but, in those wells, the Bakken will be completed as bail-out zones.”

That same spring, over in Montana, prospector Dick Findley and operator Bob Robinson did just that: They bailed out in the Bakken—in the middle member—in Montana in Mustang Field when an underlying Nisku, aka Birdbear, target didn’t work out.

The dolomitic middle Bakken is tight, but not as tight as the shale members above and below. The rock in that vertical well, in particular, had behaved unusually, though, even while it was being drilled.

“About 40 minutes after we penetrated it,” Findley said, “we got bottoms up and had a 400-unit gas increase. And we encountered about a 10-foot drilling break, which indicated porosity.

“I didn’t think there was any porosity to speak of in the middle member. That seemed pretty unusual.”

He put it aside, though. Dawn was coming. “I was going to blame it on the early morning. I hoped that my mind was just fuzzy.”

Back at the hotel in Sidney about a dozen miles from the well, “I don’t know how long I was asleep, but my eyes popped open,” he said.

“I was thinking, ‘Wait a minute. Oil isn’t in the shale’ like most people thought, including myself. ‘It looks like, in this area, the oil is in the middle member.’”

The pair bailed out in it. They made their money back.

But the well, Albin FLB 2-33, kept flowing. Robinson phoned Findley, telling him, “You know, this just isn’t declining. Do you think we have someplace to develop this?”

Findley wasn’t optimistic. It was an anomaly, he thought. But he looked. Where else might an Albin FLB 2-33 work?

North of Albin, logs of old wells that went through the Bakken didn’t show much porosity and wasn’t as high in resistivity. Looking south, however, old logs were showing the middle Bakken to have very persistent porosity—between 8% and 12% in a long trend.

“It took me a couple of days; there were maybe 20 to 25 wells I could look at. Every one of them had porosity and high resistivity for oil.”

After Findley plugged each well into his map, it began to show a consistent northwest/southeast trend—an ancient shoreline. “It looked like it was 40 miles long and 4.5 miles wide.”

He called Robinson. “I think we found a giant oil field,” Findley told him. Robinson was skeptical. “He said, ‘I kind of doubt that.’”

But the pair began leasing. They would need a lot more money. “It was going to take a couple million dollars to buy all the leases available on this trend, and Bob didn’t have that kind of money nor did I.”

Findley had given the prospect a name: Sleeping Giant. He said, “You get pretty desperate when you start naming prospects after so many years.

“It really did look like a giant oil field that was just waiting to be developed. So I called it Sleeping Giant.”

Partners, money

In the 1980s, Findley had met Cameron Smith, a New York-based oil and gas investor who matched operators with private capital via his Cosco Capital Management LLC firm. He and Robinson gave Smith a call.

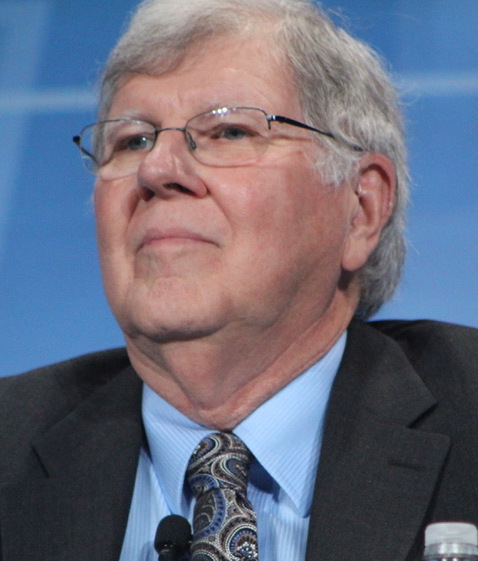

Smith had been in touch over the years with Bobby Lyle, the founder of Dallas-based Lyco Energy Corp.

Findley, Robinson and Lyle met. They leased 50,000 acres and reentered 10 verticals in the trend to check the log data. Lyco had 75% working interest and carried Findley and Robinson, as Sleeping Giant LLC, for their 25%.

Lyle said, “It was a fair deal, and we liked the people and the concept. We thought it was worth the risk and that, if it worked, there was potentially a lot of oil there.”

Nine reentries were attempted in 1997 and a tenth in early 1998. In general, they proved Findley’s theory that the middle Bakken would produce from one end of the northwest/southeast trend to the other.

Lyle believed that the sweet spot—just 10 to 15 feet thick—of the roughly 30-foot zone would have to be produced horizontally, though, and these laterals would have to be fracked.

That would be costly—at least $1.75 million each. “We didn’t have any money to really test this idea,” Lyle said.

“So I called Dick Cheney.”

He and Cheney, chairman of Dallas-based Halliburton Co. at the time, were both on the Southern Methodist University board of trustees.

Lyle said, “I told Dick what we wanted to do and asked if Halliburton was interested in participating.”

At the time, Halliburton was developing a unit to invest in E&P projects in which it could deploy new technology. It was a business development proposition that was hoped to jumpstart more oilfield activity—thus, more oilfield contracts.

Some weeks later, Lyle received a call: “They said, ‘We think this will work.’”

But oil prices were falling. A barrel had pushed past $25, but estimates of Pacific Rim demand growth had been inflated, prompting the “Asian contagion” market fallout. Meanwhile, OPEC was slow to cut back on its output.

A barrel fell to as little as $11 in December 1998. Regional spot prices were even less.

The Halliburton group asked Lyle, “What do you want to do?” He replied, “I’m not drilling a well up there with oil at $8.75 a barrel.”

Halliburton agreed. Meanwhile, it and Lyco engineers continued to draft the fracked-lateral plans. The initial ideas involved making select perforations along the wellbore and pushing a massive amount of water and sand into the rock.

“You would just pump into those perforations along the entire lateral length all at once and try to control the placement of the sand by the placement of the perforations,” Findley said.

While they waited, oil improved, exceeding $26 in December 1999 and heading to $30. The price was the best since 1985. Lyle said, “Finally, we started drilling the test well.”

The lateral

Burning Tree State 36-2H was placed about 17 miles northwest of the now four-year-old Albin FLB 2-33. The middle Bakken there was at about 10,000 feet below the surface.

The decision was made that the lateral should be driven along the top half of the roughly 30-foot section, just below the upper Bakken Shale. The drilling crew would need to keep the bit in that small window.

Lyle said, “Today … the task seems pretty simple. However, at the time, what we were doing had never been attempted. We were all a little nervous.”

Findley recalled one of the engineers saying, “This permeability is so low there’s no way this play is ever going to work. Let’s walk away. It’s just not worth doing.”

But, “Bobby Lyle said, ‘No. We’ve come this far. Let’s go ahead and drill it horizontal.’”

The lateral reached about 1,700 feet; the original plan was to take it to about 3,000 feet.

Lyle said, “The well started to torque up on us. I was concerned we were going to lose it. I told the Halliburton group, ‘We have enough exposure. Let’s stop and test the idea. If we twist off now, we may never get back here again.’

“People might have gotten cold feet. ‘If we lose the well, we’re going to leave a lot of money in the hole. And we may not convince ourselves that we ought to try this again.’ They said, ‘We think that’s a good idea.’

“So we stopped drilling.”

The frac

It was time to complete the well. Perforations had been made in preparation for the frac job. From just open holes along the horizontal wellbore, “we were surprised by the (natural) flowback we were getting,” Lyle said. “It was better than we anticipated.”

Findley and Robinson had decided to go out and watch the frac. Upon arriving, though, “there was nobody out there. Nothing,” Findley said. “We didn’t know what was going on.”

They wandered around the site. “There was this dust-covered gauge on the ground, and it had 400 pounds on it. Bob looked over to the storage tank and saw this flap going up and down on the top. We put two and two together and said, ‘My goodness. This well is flowing!’

“About that time, a tanker pulled up onto the location. The driver got out and said, ‘Well, this is my second load of oil today. I’ve already taken 400 barrels (bbl) out of this thing.’

“Bob and I were pretty happy. It was flowing naturally—without a frac.”

Still, it would be fracked; the flow, then, was even more impressive. Also, it turned out that the upper Bakken was a worthy barrier. Adding isotopes to the frac fluid, the completions engineers were able to log where the cracks went.

Findley said, “Invariably, that frac would come right up to the shale and just stop; it just wouldn’t go up into the shale.”

They didn’t lose their frac.

And, then, they waited. Would the well, like the old horizontals in the upper Bakken in North Dakota and the verticals in the middle Bakken dolomite outside of Findley’s porosity-trend fairway, just fizzle out?

Lyle said, “We didn’t want to run out and get all excited about something that, overnight, was going to (begin producing) water.

“We were cautiously optimistic.”

On May 26, 2000, Burning Tree State 36-2H came on with an official IP of 196 bbl on a quarter-inch choke from three sets of perforations in the roughly 1,700-foot lateral at about 10,000 feet below the surface. The IP was about three times that of the vertical Albin 2-33 and up to seven times the average of the vertical reentries.

More wells

Based on just the initial results, however, Halliburton was disappointed: It had signed on for only one well. Lyle had wanted Halliburton in for at least three; Halliburton would sign for only one.

Halliburton wanted now to participate in testing further. Could it yet further improve results from this generous rock?

After a couple months online, the rate just wasn’t declining.

Lyle said, “From our standpoint, we were tickled: We had what appeared to be a successful prototype, and there were no real encumbrances in terms of a commitment (with Halliburton) on a go-forward basis.

“It gave us a little bit better negotiation position.”

For Halliburton, should the play work out, the technology and expertise it could develop could translate across its business worldwide. Particularly, it would give it a position and edge in the Williston Basin to serve other producers wanting to do a Lyco-type completion.

Most frac jobs in the region were just small ones and on vertical wells. Burning Tree State 36-2H was the first fracked horizontal in the Williston Basin.

Halliburton signed a new, 10-well deal under which it became the preferred service provider.

Findley said of the middle Bakken, “Nobody would ever think you could produce oil out of such a low-permeability rock in (what became named) Elm Coulee Field.”

He recalled that, after making the brochure about his Sleeping Giant idea to take to the Lyco group to review in the summer of 1996, “I was kind of embarrassed for naming it that. It sounded a little hokey.

“Thinking back on it now, you know, it turned out to be correct.”

The neighbors

In 2000, only six wells were drilled in Richland County—Lyco’s in the Bakken and five by others in Ratcliffe, Nisku, Red River or Stonewall. Lyco had managed to remain alone in the play, but other leaseholders were all around it. Some were exploring other formations; some simply owned acreage HBPed by existing verticals.

The neighbors were watching, though. What kind of decline curve would Lyco get from its middle Bakken wells? Would the wells just sputter out? Or would they be economic?

Privately held Dallas-based Headington Oil Co. had been curious. It made a vertical, Albin 31X-28, for 130 bbl in late 1997. The hole had been bored to Red River; it was completed uphole in Bakken about a 15-minute, northerly stroll through a field from Findley and Robinson’s Albin of 18 months earlier.

In 2001, Lyco gave everyone more to talk about. It went nine-for-nine in its follow-up Bakken attempts, all horizontals, bringing them online with between 190 and 368 bbl.

Headington then went in with a horizontal—Dynneson 11X-5. The well flowed 181 bbl a day its first 12 days online; upon being fracked a couple months later, it came back on with 242 bbl.

In 2002, already 10-for-10, Lyco went another 10-for-10. Among them, it took its Peabody-Bahls 2-16H lateral about 8,500 feet for 576 bbl on Nov. 22, 2002—its biggest well yet and the longest-reach well yet in the state’s history.

Lyle said, “That gave us momentary bragging rights. It’s always fun to be part of something that is done for the first time.”

In 2002, Headington’s WCA Foundation 21X-1 came on with 445 bbl from dual laterals. One turned at 9,943 feet and went southeast for about 2,500 feet; a second went out about 4,000 feet.

By year-end 2002, Lyco had advanced to No. 5 oil producer in Montana, making 686,766 bbl that year—even advancing past several Cedar Hills anticline operators south of Richland County, Mont.

The state named the new Bakken play: Elm Coulee Field. Its first appearance on the Montana list of oil fields was at No. 5 among the all-time top 100.

In 2004, it made 7.5 million barrels (MMbbl); Lyco’s share was 4.7 MMbbl. Oil reached about $50 in 2005. Lyco went 35-for-35 that year.

Continental Resources Inc. had joined the play; it went 32-for-32. All Elm Coulee Field operators combined were 143-for-143.

By year-end 2005, cumulative field production was 27.1 MMbbl—roughly half of all the oil made in the state that year.

Lyco advanced to No. 2 oil producer, making 4.1 MMbbl that year, second only to Encore Acquisition Co. (6.4 million) and its enormous Cedar Creek anticline fields.

‘Common sense’

Fellow oil and gas explorers had dismissed Lyco’s early work, Lyle said. “They said, ‘You’re not going to make any money in Montana. You cannot make any money in the Bakken. That’s absurd.’

“A few years later, they were buying acreage all around us.”

By July 2005, Lyco and Sleeping Giant LLC had run their race—and won. The property was sold to Enerplus Corp. for $421 million.

The idea in 1996 had made 8.8 MMbbl for the partnership. Every one of their horizontal attempts was a commercial success—100%. Lyco had gone 83-for-83.

Besides the 27 MMbbl the five-year-old field had made, it had also given up some 26 billion cubic feet of associated gas. It was making 30 million cubic feet a day.

Lyle had recognized early in the Sleeping Giant program that gas gathering infrastructure would be needed in addition to more oil pipeline infrastructure. Gas flaring is allowed in the state but not in perpetuity.

Also, the gas that the wells were making was full of valuable NGL.

Lyle had gone to the gas-pipeline operator in the area and explained he would be needing gas takeaway service. Lyle was sent away. “They said, ‘Well, we don’t really think that’s likely to happen. We think that’s folly.’”

Lyle returned twice; the company refused to believe him.

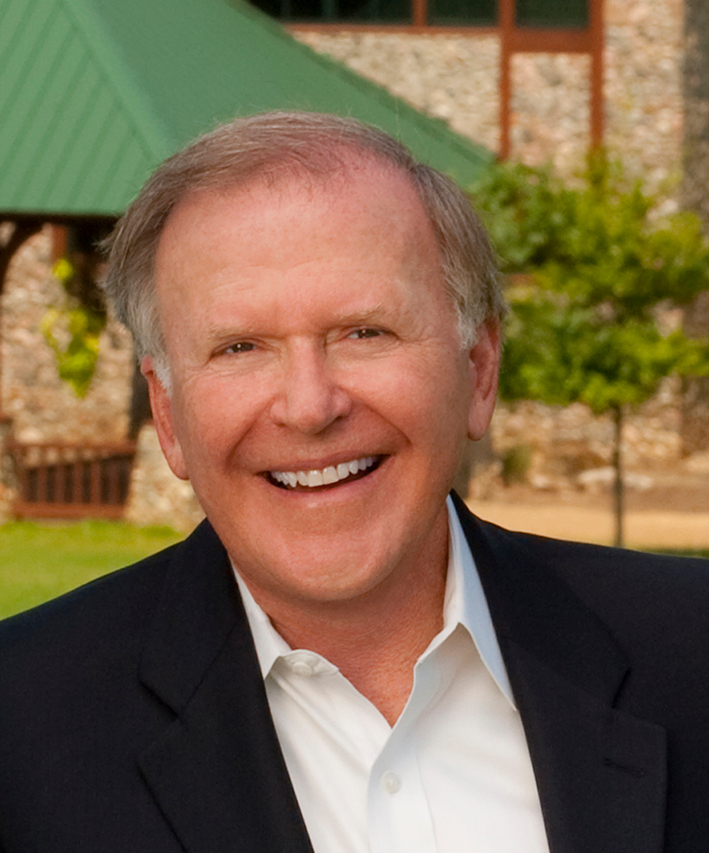

Eventually, he went to Harold Hamm, Continental’s founder and who also owned oil pipeliner Hiland Partners LLC. Hamm was the only pipeline operator who would listen to Lyle.

Hamm said, “We put in the oil gathering pipe, and we brought in the gas gathering. There was just one company gathering gas up there, and they, basically, had no competition.

“The result had been that, whatever they offered you, you had to take it. That’s not very attractive.”

Lyle and Hamm agreed to dedicate their middle Bakken gas to a new pipe; Burlington joined as well.

Meanwhile, Hamm took the Bakken idea to North Dakota, took Continental Resources public and has grown it into one of the largest U.S. oil producers.

“Bobby—well, he just has very good common sense,” Hamm said. “He had a good plan for what he thought he could do with Elm Coulee Field, and he had Halliburton in there with him, willing to spend money on the technology and apply it.

“I have a great deal of respect for him. A lot of people just didn’t give him a lot of credit.

“They should have.”

Recommended Reading

Halliburton’s Low-key M&A Strategy Remains Unchanged

2024-04-23 - Halliburton CEO Jeff Miller says expected organic growth generates more shareholder value than following consolidation trends, such as chief rival SLB’s plans to buy ChampionX.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Americas

2024-04-23 - The final part of Hart Energy E&P’s Deepwater Roundup focuses on projects coming online in the Americas from 2023 until the end of the decade.

Ohio Utica’s Ascent Resources Credit Rep Rises on Production, Cash Flow

2024-04-23 - Ascent Resources received a positive outlook from Fitch Ratings as the company has grown into Ohio’s No. 1 gas and No. 2 Utica oil producer, according to state data.

E&P Highlights: April 22, 2024

2024-04-22 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a standardization MoU and new contract awards.

Technip Energies Wins Marsa LNG Contract

2024-04-22 - Technip Energies contract, which will will cover the EPC of a natural gas liquefaction train for TotalEnergies, is valued between $532 million and $1.1 billion.