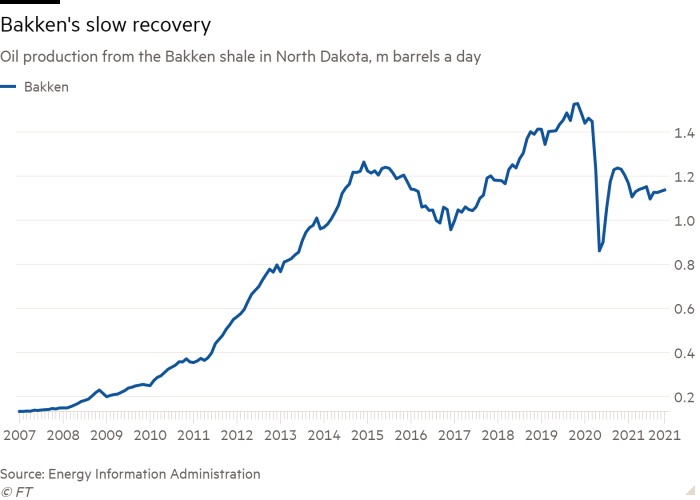

There are about half the number of rigs drilling for oil in the Bakken as there were in 2019 and output is hovering around 1.1 MMbbl/d. (Source: Hart Energy)

The Bakken oil field in North Dakota, the birthplace of America’s oil boom a decade ago, is struggling to recover from last year’s market crash even as crude prices have surged back to $80 per barrel.

It reflects a broader slowdown in growth from America’s oil patch as companies keep spending low in a bid to redirect the windfall of cash from higher prices back to shareholders. But analysts say the Bakken faces a bleak future after years of intensive drilling.

Oil producers in the Bakken are now running into the “geological reality” that after a decade of rapid development “most of the best wells have been drilled,” said Clark Williams-Derry, an analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “It helps to explain why the industry in the Bakken is sort of flatlined.”

The dwindling number of high-quality wells left to drill—those that can produce high volumes of oil for relatively low cost—will make it difficult for Bakken producers to get output back to pre-pandemic levels, Williams-Derry said.

Wells that compare favorably to today’s best drilling sites could start to run low within just two years and “things start to really fall off the cliff” in the middle of this decade, he added.

Soaring oil production transformed North Dakota over the past decade. As crude output surpassed many OPEC members, billions of dollars were pumped into local government coffers and an army of oilfield workers from around the country were drawn to the crude rush.

But last year’s oil market downturn hit the Bakken particularly hard. About 40% of the field’s output had to be turned off when the pandemic hit and fuel demand evaporated. Oil flow quickly recovered as wells were brought back into production late last year as demand started to rise again.

The recovery has been sluggish this year, however, with production failing to gather pace even as crude prices have surged past $80 per barrel, high enough to make most wells profitable.

There are about half the number of rigs drilling for oil as there were in 2019 and output is hovering around 1.1 million barrels a day (MMbbl/d), far below its pre-pandemic peak of 1.5 MMbbl/d.

The slow recovery in the Bakken has weighed on broader U.S. output, which remains about 2 MMbbl/d below 2019’s 13 MMbbl/d peak even as consumption has surged back to pre-crisis levels. It has helped to fuel the global crude price rally.

“Nobody’s viewing the Bakken as a growth engine anymore,” said Steve Diederichs, a vice president at Enverus, a consultancy.

In addition to the dwindling high quality well prospects, persistently high level of flaring—when unmarketable natural gas is burnt off at well sites—has also led some operators to turn away from the basin.

“The easiest way to clean up your emissions profile is to divest your dirtiest assets,” Diederichs said, pointing as an example to Norway’s oil major Equinor, which sold its Bakken business earlier this year.

Surging oil prices have prompted the Biden administration to call on OPEC+, the group of oil-producing nations, and American companies to step up output to help bring down the cost of petrol. Prices at the pump are at the highest level since 2014 in the US and nearing record levels in other parts of the world.

Ron Ness, head of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, said he “suspects that we’re going to see production start going upward” from early 2022, in part thanks to higher prices.

Tony Barrett, vice president of exploration at Continental Resources, the Bakken’s largest producer, said the region is still in “the middle innings” of its development and sees scope for more growth from the region.

But there are warning signs for the future of the Bakken as some of the region’s top investors have started shifting resources to other oil fields.

Continental, owned by billionaire oilman Harold Hamm, a high-profile backer of former president Donald Trump, spent $3.25 billion this month acquiring lands from Pioneer Natural Resources in the Permian Basin, which spans Texas and New Mexico.

Barrett told the Financial Times it was “absolutely not true” they did the deal because of a lack of “inventory” in the Bakken, saying the company could expand for another decade without the Permian assets.

Still, the deal echoes a broader shift of spending and industry activity away from aging shale areas like the Bakken and toward the Permian, which is seen by investors as the most viable growth engine for companies.

ConocoPhillips, another major Bakken producer, has spent nearly $20 billion over the past year building up its Permian business, including buying Royal Dutch Shell’s assets there for $9.5 billion. Timothy Leach, a vice president at the company, told analysts earlier this month that the Bakken was at its “optimal plateau.”

“It’s almost like the people who are operating in the Bakken don’t have a lot of confidence in it,” said Williams-Derry. “The industry is focusing more on other parts of the U.S., particularly the Permian. Places that don’t face that imminent decline in oil quality.”

Recommended Reading

Oceaneering Won $200MM in Manufactured Products Contracts in Q4 2023

2024-02-05 - The revenues from Oceaneering International’s manufactured products contracts range in value from less than $10 million to greater than $100 million.

E&P Highlights: Feb. 5, 2024

2024-02-05 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including an update on Enauta’s Atlanta Phase 1 project.

CNOOC’s Suizhong 36-1/Luda 5-2 Starts Production Offshore China

2024-02-05 - CNOOC plans 118 development wells in the shallow water project in the Bohai Sea — the largest secondary development and adjustment project offshore China.

TotalEnergies Starts Production at Akpo West Offshore Nigeria

2024-02-07 - Subsea tieback expected to add 14,000 bbl/d of condensate by mid-year, and up to 4 MMcm/d of gas by 2028.

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for Third Time in Four Weeks

2024-02-09 - Despite this week's rig increase, Baker Hughes said the total count was still down 138 rigs, or 18%, below this time last year.