How can you obtain new capital from your producing assets without giving up control over their operation, and more important, without letting the upside go? There are a number of ways, and they are gaining new popularity in a difficult M&A environment that may preclude an outright sale of the assets. A few months ago, Morgan Stanley Capital Partners agreed to pay $300 million of Apache Corp.'s $500-million acquisition of Gulf of Mexico assets from Shell, and recoup its investment in production rather than cash. This put the volumetric production payment (VPP) in focus for the first time in a while. Earlier in 2003, Morgan Stanley backed Triana Energy Holdings, Charleston, West Virginia, when it acquired Columbia Energy Resources from utility NiSource for $330 million in cash-and Triana agreed to honor the forward sale of 94 billion cubic feet of gas to NiSource as part of the payment, through 2006. But several other VPP deals have been closed this year and additional ones are in the works. The economic environment today is particularly well suited for them-low interest rates combined with properly hedged, high commodity prices make them a good financing choice for producers, especially if they are tied to predictable, long-life properties such as those found in the San Juan Basin, Appalachia, Texas or the Midcontinent. VPPs were popularized by a former Enron Corp. financing unit in the 1990s. That firm alone set up more than $2 billion of VPP deals with companies as diverse as publicly traded Forest Oil Corp. and privately held Zilkha Energy Co. A producer can monetize producing fields in one of two ways: through an outright sale or through a VPP. In the latter, the producer sells a portion of his reserves for a fixed price and time period for cash at closing, and repays the capital provider by delivering scheduled physical production carved out of total production volumes from the properties dedicated to the VPP transaction. The decision to do a VPP instead of a sale can be driven by the tough M&A climate that exists today, with high commodity prices widening the valuation gap between buyers and sellers. Buyers do not believe the forward curve; sellers do. The VPP buyer always hedges. A VPP is not treated as debt on the producer's books; it's accounted for as a sale or deferred revenue. A second benefit is that the producer retains the upside production from the properties, continues to operate them and receives cash flow from the tail end of production after the VPP buyer gets the scheduled volume. A third benefit? VPPs are bankruptcy-proof and non-recourse to the producer because the buyer (capital provider) directly owns title to the barrels or cubic feet of reserves. The "interest rate" of a VPP can be thought of as a blend of the actual price of barrels or cubic feet produced and their forward price, including the effect of any hedges. Or put another way, it can be the cost of capital used to discount the cash flow from the production back to a present value. The producer has an amount he wishes to "borrow" and the capital provider has a rate of return it needs to receive. VPP providers can be financial firms or end users, pipelines or utility-related entities that want the oil or gas supply that comes by buying the VPP. Says one Houston-based capital provider who is considering a VPP, but asked not to be named, "We feel the seller or producer is getting them cheap nowadays in terms of the embedded interest rate being so low. This is a reflection of low interest rates in general and a positive view of the commodity as well. Of course it's to the producer's advantage, but is it a fair risk-reward for the VPP purchaser?" Producers use VPPs to fund acquisitions, as Apache did, or can redeploy the proceeds for additional drilling or debt reduction. Recent deals In August, Texas Municipal Gas Corp. (TMGC), which is managed by Municipal Energy Resources Corp. (MERC) in Houston, completed a $266-million VPP with Dominion Exploration & Production Co. The deal took the form of an overriding royalty interest in more than 3,200 producing wells throughout the Sonora Field in West Texas. Dominion will operate the properties as before and retain all production derived from developing those fields, in excess of the volumes dedicated to the VPP transaction. The VPP starts by dedicating 82 million cubic feet per day and declines over four years to about 5 million a day at the end of the transaction period. In total, TMGC will receive 66 billion cubic feet (Bcf) of gas during the next four years, which it will deliver to Texas utilities participating in its gas acquisition program. "We had a strong discount rate for Dominion, in the single digits, and we factored in attractive swap prices above $4.50 per million Btu," says Mike Rosinski, MERC senior vice president. "Because TMGC's credit rating is stronger than that of some producers, and because our vehicle can go out for a longer term, TMGC can lock in long-term commodity prices at attractive rates for a producer who might not otherwise be able to do so." The VPP gives Dominion capital to deploy elsewhere, without selling the properties themselves. It also avoided the malaise of the acquisition and divestiture market where, until recently, buyers and sellers did not see eye to eye on valuations. "Naturally we're pleased," says Fred G. Wood III, senior vice president, financial management, Dominion E&P. "By doing this deal, we're retaining all of the field's growth potential while capturing a piece of future value today. We've effectively hedged the current gas price for our shareholders, but we've done it without raising the usual credit or liquidity issues companies often face when they use traditional hedging instruments. "Cash raised by this sale is now available for debt reduction and reinvestment." TMGC currently has 85- to 90 million cubic feet a day and it would like to get up to 250 million a day, says MERC president Bob Murphy. "Our preference is Texas onshore, and the longer the life, the better, but we would look elsewhere, and have." TMGC can buy VPPs or royalty interests using proceeds from taxable or tax-exempt bonds to be issued to finance the purchase. Its VPPs can have terms for as long as 10 years. A satisfied VPP customer in another deal is Wapiti Energy LLC, Houston. It has made five acquisitions to increase its working interest in shallower gas zones in the decades-old Conroe oil field north of Houston that is operated by ExxonMobil. "This is the kind of property that fits a VPP, because it is stable, long-lived production. It will do a billion BOE before it's through," says John Faulkinberry, Wapiti vice president. The company owns 100% working interest in zones at about 4,000 feet and is drilling gas wells that flow 500,000 to 750,000 cubic feet a day. In April 2001, Wapiti sold an $11-million VPP to Duke Energy Capital to fund its first purchase in the field. At the time, the 2000 start-up did not have a lot of other capital choices available. As Wapiti bought additional interests in the field it conveniently added those barrels to the VPP simply by amending the existing documents. "Quite frankly, because [partner] Dick Agee and I were doing this on our own, we needed to borrow most of the money to make the first acquisition. If you compare a VPP to mezzanine funding, we could get more money through the VPP structure." Wapiti bought back those barrels and took the deal to a commercial bank recently when Duke Energy Corp. disbanded its finance subsidiary earlier this year. Faulkinberry advises producers to be sure to negotiate a commodity price to use when the VPP provider's hedge expires, and to include a clause on how to terminate the VPP if the producer wants to buy the reserves back-or if production ends up being lower than estimated during the term of the VPP. "We would do a VPP again for the right property," he says. New providers Several of the new mezzanine and private capital providers that have opened up this past year in Houston say they will do VPPs. More established firms also consider them. "I think the institutions pursuing them have had some difficulty because of the volatility of gas prices," says Lynn Bass of Weisser Johnson & Co., a firm with an interest in VPPs. "By the time you are trying to close, gas has gone up or down substantially." Indeed that is why a price hedge normally accompanies the VPP. Adds Bass: "A VPP, or similar structure, allows asset buyers to 'pay up' for the proved developed producing portion of an acquisition." Undaunted, an East Coast utility has opened a Houston-based producer financing unit recently, although at press time it was not ready to talk about details publicly. But like any utility, it is naturally short gas supply and long demand. Rather than start an E&P subsidiary like some utilities have done to ensure adequate gas supply, it chose to create a producer-financing arm to address this need through VPPs and other structures. Oil and Gas Investor has learned that its first VPP deal closed this past summer, with a private Texas independent. With the resulting VPP, the net present value net to the seller was equal to or better than if the independent had sold the assets outright. Net profits interest Another way to monetize producing assets is through the sale of a net profits interest. An NPI is a sale of real property, so it is not accounted for as deferred revenue. The producer or seller, however, retains a significant reversionary interest in the properties-that is, an interest that reverts back to him after the NPI buyer gets a specified return. In September 2003, GeosCapital, the new Houston-based financing unit of J.M. Huber Corp., closed its first asset monetization for a producer, but it took a different tack, even though it will buy VPPs as well. A partnership with an institution was formed that purchased an NPI in a gas-producing property in the Midcontinent. It did so by paying the private operator of the property $105 million. Since as much as 50% of the production was composed of gas liquids, the partnership entered into long-dated hedges including a seven-year hedge on the liquids production, explains Carl J. Tricoli, GeosCapital president. As in a VPP, the producer will continue to operate the properties through his working interest and participate in upside through the reversionary interest. In this case the back-in should happen within 10 years, Tricoli says. A sale of the entire working interest was considered, but since the property in question had such long-lived reserves-up to 40 years-it was difficult for the seller and potential buyers to agree on a value of the tail-end production so far forward. "Unlike a VPP that is debt-like in its attributes, the sale of a net profits interest results in the transfer of a larger percentage of a property than a VPP would allow," says Tricoli. "The tradeoff is that it may cost slightly more." The partnership enjoys a passive, steady cash flow stream without shouldering the burdens of AFEs (authorization for expenditure to drill or service a well), environmental liabilities or any other concerns associated with operating or a working interest. "This is a low-maintenance way to own reserves without having to do operations," says Tricoli. "It gives the partnership attractive returns relative to today's low interest rates. And, it's a way for a producer to take advantage of high commodity prices in a difficult selling environment, without giving up the upside."

Recommended Reading

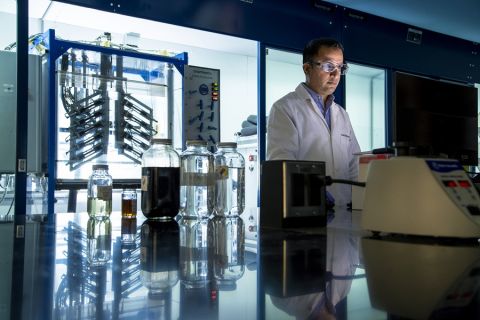

Defeating the ‘Four Horsemen’ of Flow Assurance

2024-04-18 - Service companies combine processes and techniques to mitigate the impact of paraffin, asphaltenes, hydrates and scale on production—and keep the cash flowing.

Tech Trends: AI Increasing Data Center Demand for Energy

2024-04-16 - In this month’s Tech Trends, new technologies equipped with artificial intelligence take the forefront, as they assist with safety and seismic fault detection. Also, independent contractor Stena Drilling begins upgrades for their Evolution drillship.

AVEVA: Immersive Tech, Augmented Reality and What’s New in the Cloud

2024-04-15 - Rob McGreevy, AVEVA’s chief product officer, talks about technology advancements that give employees on the job training without any of the risks.

Lift-off: How AI is Boosting Field and Employee Productivity

2024-04-12 - From data extraction to well optimization, the oil and gas industry embraces AI.

AI Poised to Break Out of its Oilfield Niche

2024-04-11 - At the AI in Oil & Gas Conference in Houston, experts talked up the benefits artificial intelligence can provide to the downstream, midstream and upstream sectors, while assuring the audience humans will still run the show.