Arguably no company did more to boost U.S. oil production and lower sky-high fuel prices during the pandemic than the little-known Mewbourne Oil Co.

U.S. crude volume rose by more than 600,000 bbl/d on average from 2021 to 2022 as global demand rebounded. But Mewbourne’s output shockingly almost tripled during the pandemic, accounting for almost 150,000 bbl/d of the national growth when most companies conservatively constricted.

The 58-year-old company from tiny Tyler in rural East Texas certainly is not a household name—many people within the energy sector are unfamiliar with it—but Mewbourne’s surging supplies are making it harder than ever to remain under the radar, especially with national energy security such a huge concern.

“We’re patriots at the Mewbourne Oil Co., but it’s really just a byproduct of some hard work … and some good fortune,” said Mewbourne President and CEO Ken Waits in an exclusive interview with Hart Energy. “We’ve grown as rapidly as anyone in the business in the last few years, and it’s all been organic.”

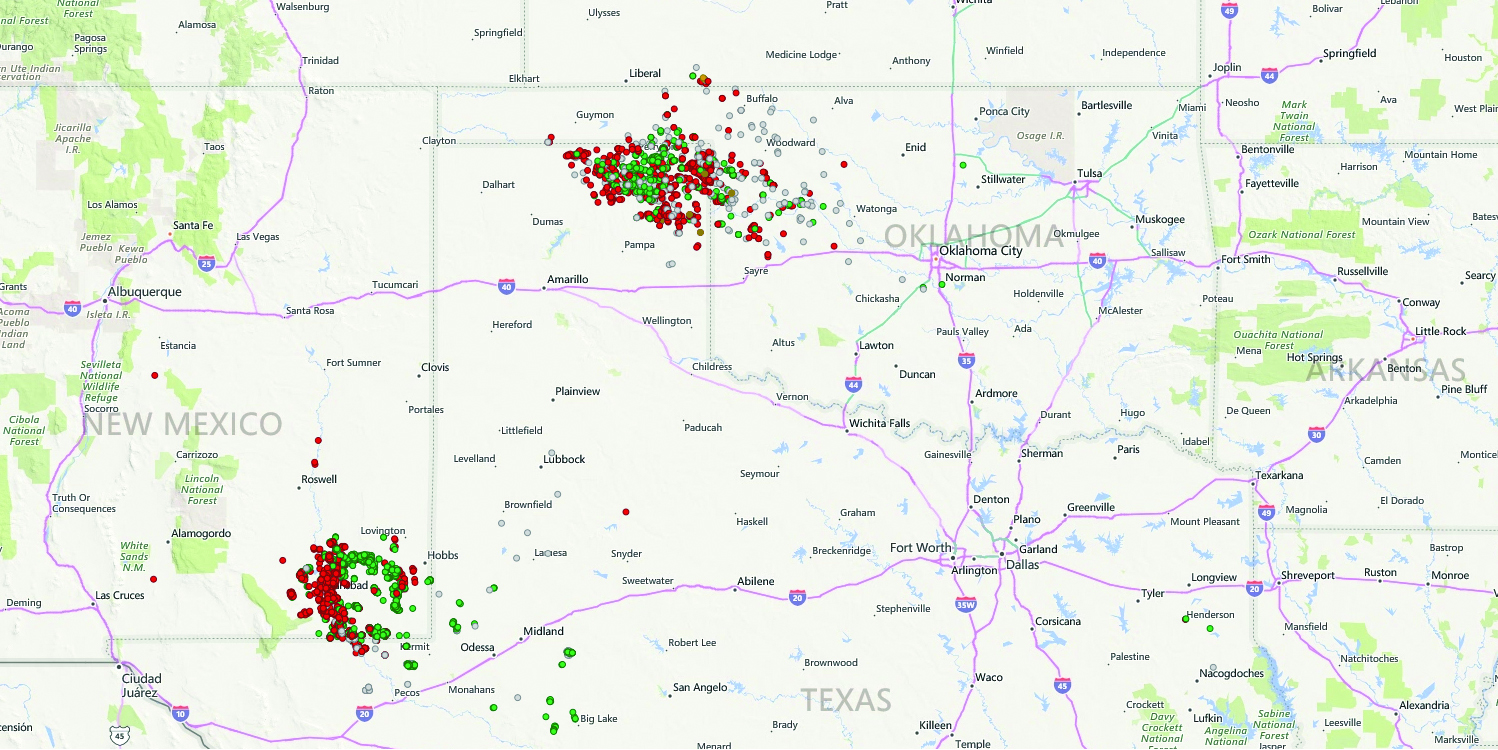

Privately held drillers helped lead much of the pandemic-era growth as the publics temporarily scaled back, but none of the private players were as active as Mewbourne, especially in southeastern New Mexico.

With about 20 drilling rigs operating in the Permian Basin and another five in the Midcontinent region, Mewbourne is the top private producer in the Permian and the most active overall driller in the booming Delaware Basin. Waits said Mewbourne’s total operating volumes now exceed 400,000 boe/d.

If we were to play a game of ‘one of these things is not like the others,’ Mewbourne is the oddball leading the pack in drilling activity in the Permian’s Delaware—possibly the hottest basin in the world—out of a top six that also includes Occidental Petroleum, EOG Resources, Devon Energy, ConocoPhillips and, biggest of all, Exxon Mobil, according to East Daley Analytics.

“Mewbourne was in hypergrowth mode and they still are,” said Stephen Sagriff, Enverus senior

vice president for intelligence.

“Everyone is kind of wondering and asking and learning who they are now. They’re this private family company that almost no one knows about,” Sagriff said, “But they’re eating up so many valuable resources, controlling 6% or 7% of the total rig count in the Permian.”

Oh, and in case you are wondering: No, the company is not for sale, Waits insisted.

How did this happen?

The company’s website looks like it was created in the 1990s and could be found only by asking Jeeves.

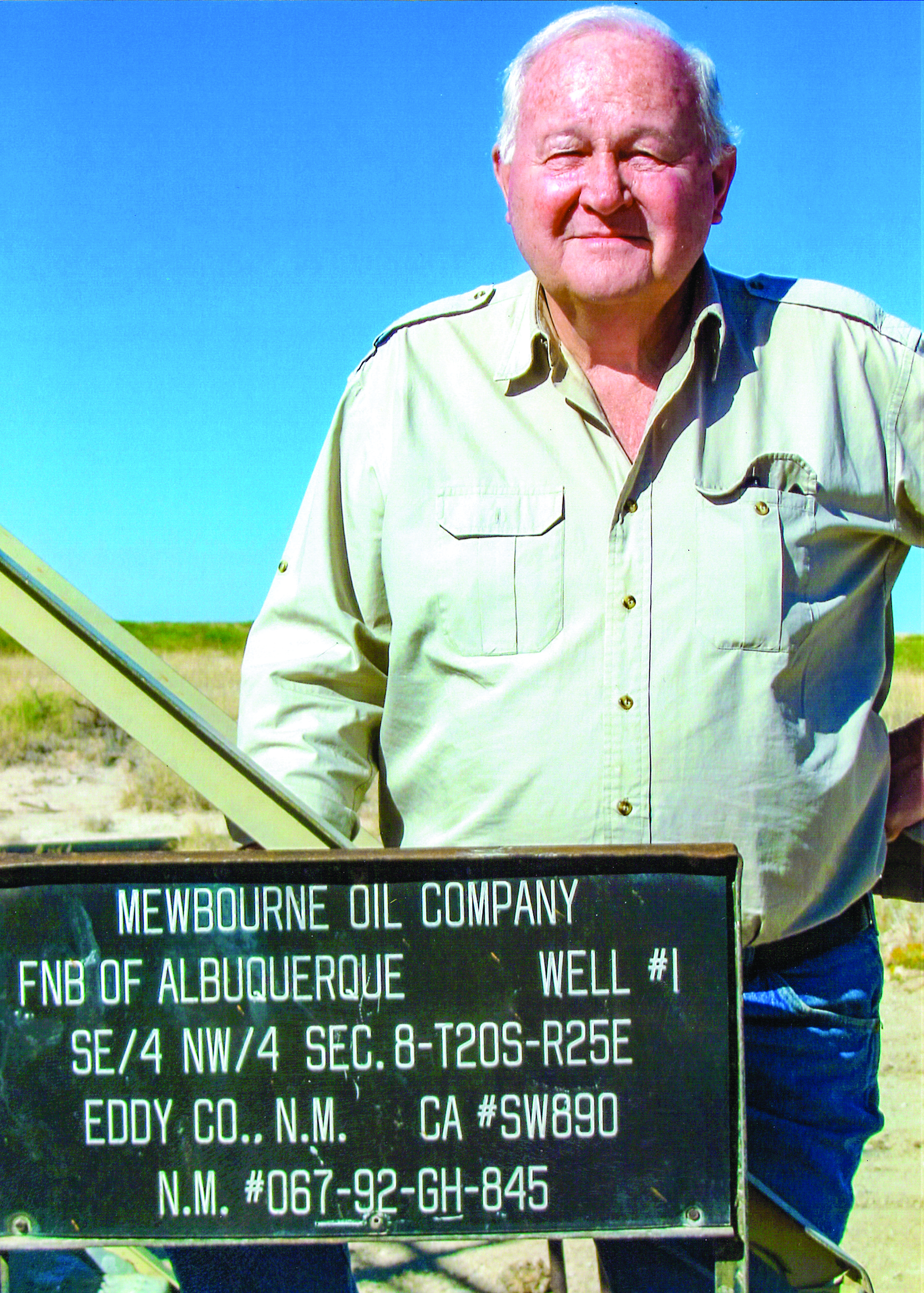

The intentionally simplified homepage focuses on a “meet our founder” section that highlights Curtis Mewbourne, who died in June 2022 at 86 after living to see his company’s skyrocketing growth.

And with years of estate planning and management succession training, the family company will remain just that, said Waits, who joined Mewbourne Oil 40 years ago out of college and never left.

“They were there before the boom. That carries a lot of advantages. You’re the first one to the prize if you think about it that way. It’s better to be lucky than smart, but they’re both.”—James Taylor, East Daley Analytics

Mewbourne first entered the Permian’s western lobe in New Mexico more than 50 years ago as a conventional natural gas play and slowly grew over the decades to its current position of more than 300,000 gross acres. Some of the company’s positioning was clearly fortuitous as the tight oil boom took hold roughly a decade ago.

“They’ve been in the Delaware a very long time,” said James Taylor, senior analyst for East Daley. “They were there before the boom. That carries a lot of advantages. You’re the first one to the prize if you think about it that way. It’s better to be lucky than smart, but they’re both.”

By the time 2020 was getting underway, Mewbourne was operating nearly a dozen rigs and had quietly outpaced the Midland Basin’s Endeavor Natural Resources to become the top private player in the Permian by volume.

But, unbeknownst to anyone in the industry, including the roughly 400 employees at Mewbourne, the company was just getting started.

When the pandemic took hold in early spring 2020, everyone slammed on their brakes. And, at least at first, Mewbourne was no different. But that quickly changed after mid-2020.

As Waits put it, Mewbourne simply stuck with following its long-term, “contrarian” strategy of taking advantage of low oilfield services costs—even when oil and gas prices cratered along with global demand.

“We’ve learned the best time to be drilling wells is when costs are low,” Waits said. “You need to maintain a strong balance sheet, and it takes the courage to drill when nobody else is doing it.”

He cited the famous investing advice, “Buy when there’s blood in the streets,” which is typically credited to Baron Rothschild of the famous banking family. Waits also quickly quoted the industry standard, “The cure for low oil prices is low oil prices.”

The strategy is not to focus on oil prices or rig counts or volumes, he said. Instead, the impetus is on low finding costs, which are the “Holy Grail” for the company.

“It’s consistent with how we’ve managed the business over the long term,” Waits said. “We were just a little smaller in the prior down cycles, and people didn’t notice quite as much what we were doing.”

And Mewbourne admittedly become even more aggressive during the pandemic.

“With COVID, the rig count collapsed and well costs adjusted accordingly. We felt like it was a great time to be drilling wells because of our attractive prospects, the attractive cost environment, and we believed oil prices were eventually going to be higher,” he said. “Being privately owned, we can do some things that would be difficult for a publicly owned company.”

In summation, “The last few years have been just exceptional for us.”

But it also was not that simple.

Sagriff noted that Mewbourne had been active in recent years, but never topped any charts in activity growth. “That completely flipped post-COVID.”

“There was a patience they exhibited and then, as soon as the time was perfect, they jumped on it and skyrocketed,” Sagriff said. “They had a lot of capital saved up for the right time. The softness in the market opened the door, and they certainly took advantage.”

But it was even more daring within the context, fear and panic of 2020, he said. “It seemed crazy at the time. We were in such a depressed market with oil prices, and no one had a clue when the world would open back up again.

“There was a patience they exhibited and then, as soon as the time was perfect, they jumped on it and skyrocketed.”—Stephen Sagriff, Enverus

“The publics were just trying to maintain production if they could, and most couldn’t,” Sagriff added. “Mewbourne was doing the opposite and growing massively.”

In terms of volume, Mewbourne started 2019 with about 75,000 bbl/d of crude output in the Permian and entered 2023 with 210,000 bbl/d, according to Enverus. The Permian oil and gas volumes alone now add up to about 350,000 boe/d, he said.

“No one compares with the sheer volumes and growth rate.”

Where did they come from?

A native of Shreveport, La., Curtis Mewbourne made the fateful choice to major in petroleum engineering at the University of Oklahoma.

He graduated in 1957 and joined the U.S. Army. He entered the oil sector with the Arkansas Fuel Oil Co. and later joined the First National Bank in Dallas. But he left the bank in 1965 to start Mewbourne Oil.

According to his obituary, “The company’s initial assets were two used chairs and a desk given by his former employer … the balance of a monthly paycheck, and one very dedicated and tenacious employee who had to use the payphone in the lobby to make calls.”

Mewbourne started out in the Midland Basin with relatively middling success and expanded to the New Mexico side of the Permian in 1970 without finding much more. Mewbourne eventually hit it big in 1973 with a natural gas well along New Mexico’s Pecos River.

“In the ’70s, in his words, ‘The struggle for survival ended and the long journey to victory began,’” Waits said of Curtis Mewbourne.

“Those were interesting times,” he continued. “We didn’t have the private equity business we have today, so young people who were starting their own businesses had to bootstrap things. He took his last paycheck, a lot of talent, a lot of passion and a lot of courage and founded the Mewbourne Oil Co. He wanted to build a company one deal at a time.”

Waits, a fellow OU petroleum engineering graduate, said he met Mewbourne before he graduated when the company was just starting to recruit new employees out of college.

He worked in the Permian and Midcontinent oilfields for a few years before being transferred to Mewbourne headquarters to work more closely with the founder and CEO.

“He was one of the greatest oilmen of his generation,” Waits said. “All of us at the Mewbourne Oil Co. miss him every day. He was an amazing man, and his enthusiasm and energy were contagious. I knew him as well as I knew my father.

“But the company is stronger today than we’ve ever been, by any measure. The family is committed to the business, our finances are stronger than ever, and we have more talented people than we’ve ever had. And that’s a real credit to the hard work he did over the generations.”

What’s next?

While U.S. volumes remain on the rise for now, the rest of 2023 has a murkier outlook with weaker oil and gas prices, a shrinking drilling rig count and natural gas takeaway constraints from the Permian.

But Mewbourne still has not slowed down.

“The smaller privates have scaled back a bit in the Permian,” said Taylor of East Daley. “But Mewbourne is still up. They’re like a large independent producer, so they can operate from an advantageous position.”

Waits acknowledged that Mewbourne’s scale matters.

“The service companies will return our phone call,” Waits said with a laugh. “We have great relationships with our service company partners, but scale has been a benefit the last few years in terms of drilling activity.”

Growth will not continue to occur at the same rapid pace though, he said. “There aren’t many emerging Wolfcamp shale plays popping up on our radar these days. But I also try to be mindful that drilling inventory is a dynamic figure; it’s not a static number. As we innovate and as technology allows, we can prove up new resources.”

“We try to take a managed approach, and we’re not necessarily swinging for the fences. We’ve generally referred to it as ‘small ball,’ to use a baseball analogy. But we’ve been very pleased with the results.”—Ken Waits, Mewbourne

Mewbourne is currently testing new zones within the Wolfcamp and Bone Spring plays that appear promising, he said.

The company aims to maintain its organic growth and not focus on major dealmaking, even though Waits will not rule out any uncharacteristic acquisitions.

“We try to take a managed approach, and we’re not necessarily swinging for the fences,” he said. “We’ve generally referred to it as ‘small ball,’ to use a baseball analogy. But we’ve been very pleased with the results.”

Sagriff calls Mewbourne a great “ground-game operator, picking up a new section here or there” without making any big M&A headlines.

“They’re always adding on developed drilling areas in small packages to maintain productivity,” he said. “They don’t need to acquire. It’s a very fortuitous position.”

At the same time, Waits said Mewbourne is embracing the energy transition—he calls it “energy addition”—and is avoiding nearly all venting and flaring. Mewbourne is capturing 99.8% of

its natural gas in New Mexico, he said, and using much more recycled water.

“People think the privately owned companies don’t have to worry about ESG,” Waits said. “But I think ESG is in the DNA of the Mewbourne Oil Co. We particularly think about responsible

long-term operations, and we want to be a good employer, partner and environmental steward.”

Curtis Mewbourne kept thinking about the next generation and gave back to his alma mater and other universities—partly for recruiting purposes—and the University of Oklahoma in 2007 renamed its College of Earth and Energy for Mewbourne.

Earlier this year, in consultation with Waits, the college launched the new GeoEnergy Engineering program within the college’s Mewbourne School of Petroleum and Geological Engineering.

The new program is “aimed at meeting the demand for education in emerging energy fields such as geothermal energy, hydrogen energy, renewable energy, energy storage and CO2 capture and sequestration,” according to the school’s announcement.

Curtis Mewbourne believed strongly in investing in the future generations and Waits said he is determined to see that vision through, especially as petroleum engineering enrollment numbers have collapsed nationwide.

“I think the industry has a great challenge in front of us,” Waits said. “People are beginning to understand that the oil and gas business is going to be here for decades to come, and we’re going to need great people in the years to come. There’s an opportunity for talented young people in this business, and many people like myself are getting older and there’s a great crew change that is happening.

“And we’re committed to being here for generations to come.”

Recommended Reading

US Refiners to Face Tighter Heavy Spreads this Summer TPH

2024-04-22 - Tudor, Pickering, Holt and Co. (TPH) expects fairly tight heavy crude discounts in the U.S. this summer and beyond owing to lower imports of Canadian, Mexican and Venezuelan crudes.

US Gulf Coast Heavy Crude Oil Prices Firm as Supplies Tighten

2024-04-10 - Pushing up heavy crude prices are falling oil exports from Mexico, the potential for resumption of sanctions on Venezuelan crude, the imminent startup of a Canadian pipeline and continued output cuts by OPEC+.

Exxon’s Payara Hits 220,000 bbl/d Ceiling in Just Three Months

2024-02-05 - ExxonMobil Corp.’s third development offshore Guyana in the Stabroek Block — the Payara project— reached its nameplate production capacity of 220,000 bbl/d in January 2024, less than three months after commencing production and ahead of schedule.

Paisie: Economics Edge Out Geopolitics

2024-02-01 - Weakening economic outlooks overpower geopolitical risks in oil pricing.

ARC Resources Adds Ex-Chevron Gas Chief to Board, Tallies Divestments

2024-02-11 - Montney Shale producer ARC Resources aims to sign up to 25% of its 1.38 Bcf/d of gas output to long-term LNG contracts for higher-priced sales overseas.