Golden Pass LNG in Sabine Pass, Texas, is among the permitted projects on the Gulf Coast; a swarm of LNG tankers can be seen delivering to Europe on Rextag’s DataLink program; an LNG tanker anchors at a small gas terminal island at Salamina, Greece. (Source: Hart Energy; images from Hart Energy, Rextag, Aerial-motion/Shutterstock.com)

On the first Friday in April, Energy Pacific drifted casually through the waters of the southern Gulf of Mexico. The 2-year-old LNG tanker, more than three football fields long and displacing 114,000 tons, posted a destination of “open sea for orders.”

Two other LNG tankers—Methane Jane Elizabeth and Flex Rainbow—also plied the southern Gulf with similar “destinations.” Eventually, a buyer somewhere and a seller somewhere else will agree to terms and the ships will drift back to the business of transporting and delivering cargo. Until then, the three vessels cannot be certain of their direction.

Something like the LNG industry as a whole these days.

President Joe Biden has worked out a deal with the European Commission to ensure that U.S. LNG sales to Europe increase from 22 Bcm (3.3 Bcf/d) in 2021 to 50 Bcm (7.5 Bcf/d) in 2030. That would appear to be positive for the industry, but it’s not an unexpected turnabout from a president who promised a rigorous climate agenda. It can be seen, however, as an expected political move from a president who sees an opening to cut Europe’s dependence on Russian energy.

The announcement of the agreement with the EU made clear that one of the goals was to reduce European dependence on fossil fuels. No matter how long the Russia-Ukraine war lasts, most of Europe has already lost confidence in Russia’s reliability as an energy supplier, especially after it invaded its customer.

Status: U.S. plants

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) reports that U.S. exports of LNG set a record in 2021, averaging 9.7 Bcf/d. In December, exports to Europe alone averaged 6.7 Bcf/d, a record that has already been surpassed in 2022.

Belgium’s imports of U.S. LNG went from zero in the last half of 2021 to 13.8 Bcf in January. France’s LNG imports rose seven-fold since August 2021 to over 50 Bcf in January. Exports to the Netherlands tripled and exports to Italy doubled.

That is not a response to presidential policies but to market conditions, which in this case are influenced by war on the continent. The U.S. benchmark Henry Hub price for natural gas on April 4 for May delivery was $5.72/MMBtu. The Asian price on the Japan Korea Marker was in the mid-$30s. The European price, which is the Dutch Title Transfer Facility index, topped them both in the low-$40s.

Even with South Korea and China, the top U.S. LNG customers, paying in the mid-$30s, it’s hard for a trader to resist supplying customers willing to pay in the $40s. But market prices can change and U.S. LNG capacity is not unlimited. Contracts are contracts, but tankers carrying LNG cargo for sale on the spot market can be diverted.

In fact, Japan agreed to divert some LNG cargoes to Europe in February. Here, the reason was geopolitics—the decision was made after diplomatic consultations with the U.S. and EU. Kevin Book, a managing director at ClearView Energy Partners LLC, termed Japan’s action “extraordinary” but doesn’t expect it to continue. Japan is an energy-poor country and cannot be called upon to keep making contributions that go against its own interests.

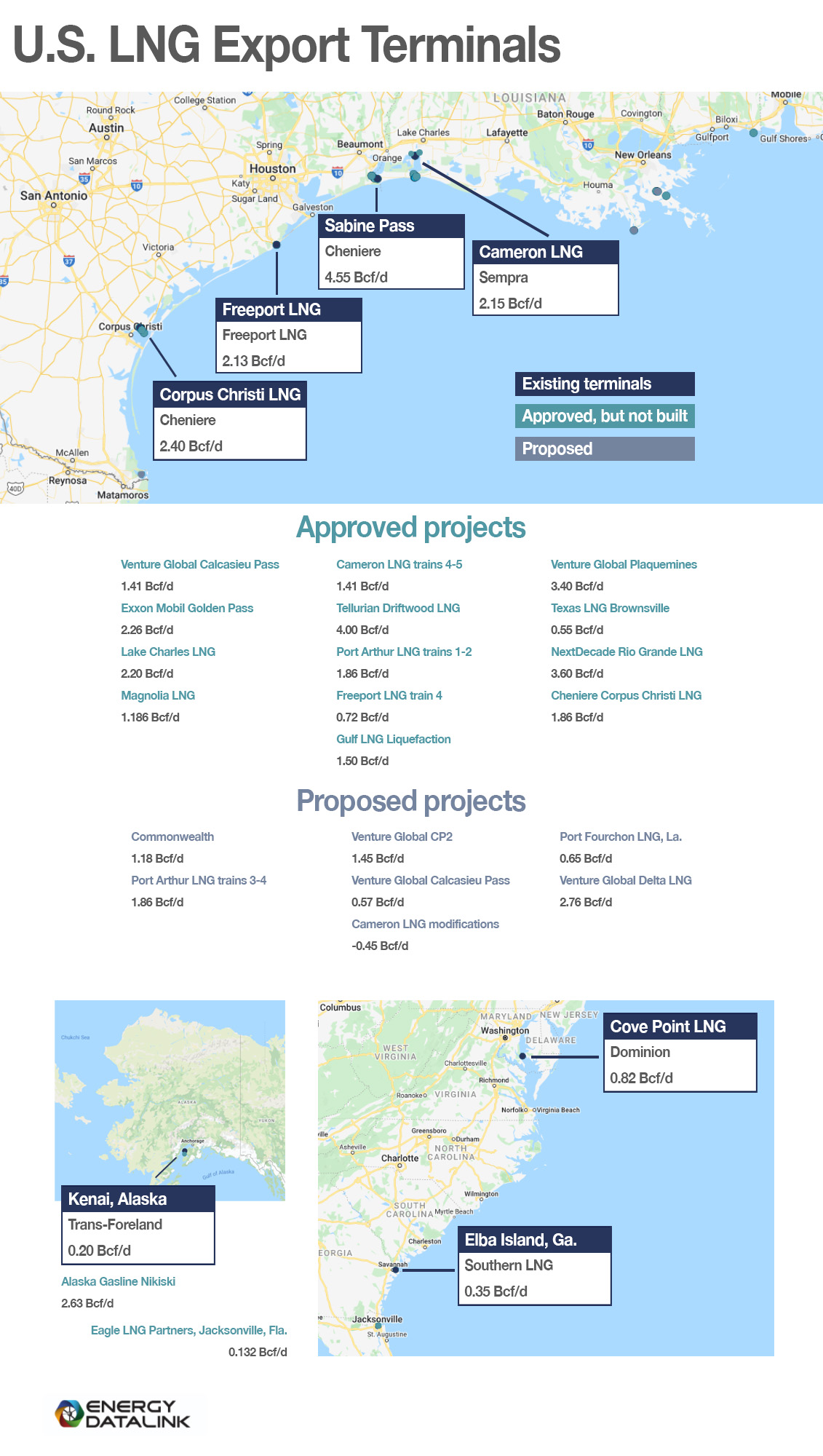

The Gulf Coast is home to only four of the country’s seven LNG liquefaction and export terminals, but those four represent 89% of capacity. Of the 22 approved and proposed projects on record with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), only two are not planned for the Gulf Coast.

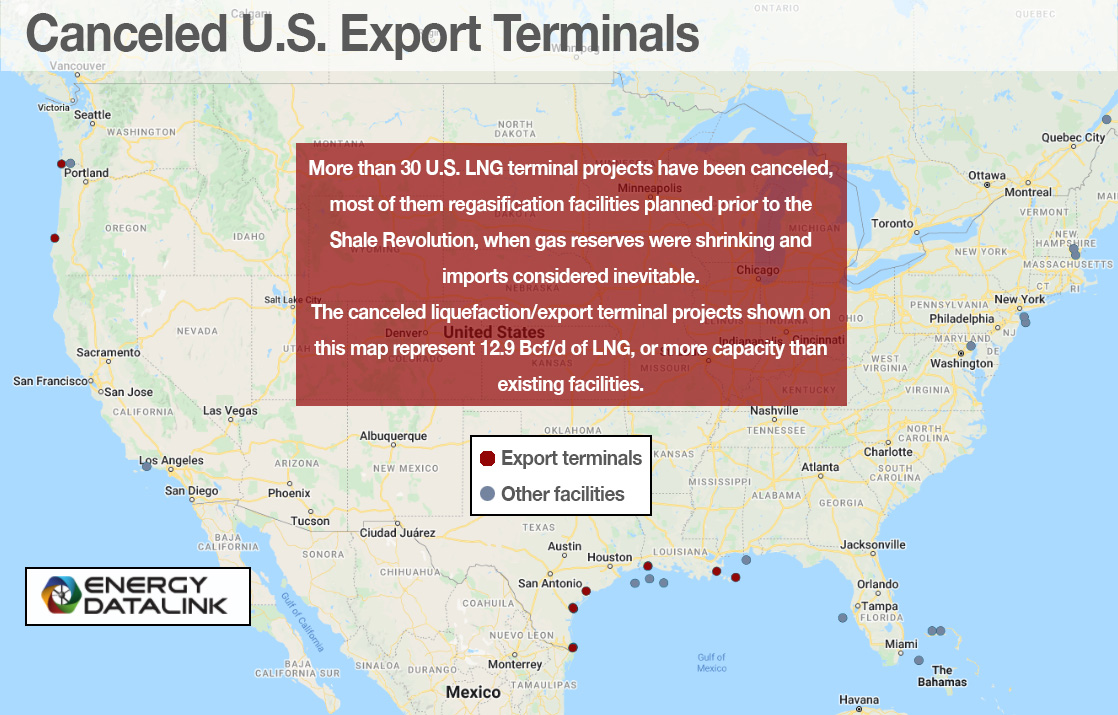

The combined capacity of the approved and proposed terminals would be about 34 Bcf/d, compared to existing capacity of 12.6 Bcf/d. Not all will be built, of course, and the U.S. coasts are littered with the discarded blueprints of canceled facilities.

Status: at sea

The EIA expects U.S. production of natural gas to average 96.7 Bcf/d in 2022, with consumption of 84.6 Bcf/d. Production increases are expected to be modest this year, so where will the market find the extra LNG to ship to Europe?

One answer is to divert tankers on their way to Asia to European terminals. That would solve the Russian energy gap issue but would jack up prices in Asia. So far, Japan’s answer to higher gas prices is to restart nuclear plants. China’s answer is to substitute cheaper coal for gas.

On the first Monday of April, the LNG fleet to nowhere—Energy Pacific, Methane Jane Elizabeth and Flex Rainbow—remained at more or less stationkeeping in the Gulf of Mexico. No jaunts to Europe. Not yet. No trips to Asia through the Panama Canal. Just waiting for direction. Just waiting.

Recommended Reading

Energy Transfer Asks FERC to Weigh in on Williams Gas Project

2024-04-08 - Energy Transfer's filing continues the dispute over Williams’ development of the Louisiana Energy Gateway.

Apollo Buys Out New Fortress Energy’s 20% Stake in LNG Firm Energos

2024-02-15 - New Fortress Energy will sell its 20% stake in Energos Infrastructure, created by the company and Apollo, but maintain charters with LNG vessels.

Williams CEO: Louisiana Energy Gateway Start Temporarily in Limbo

2024-03-21 - Williams CEO Alan Armstrong said the project still moving forward after hitting a snag in a dispute with Energy Transfer but lacks a definitive start date.

Canada’s First FLNG Project Gets Underway

2024-04-12 - Black & Veatch and Samsung Heavy Industries have been given notice to proceed with a floating LNG facility near Kitimat, British Columbia, Canada.

Venture Global Acquires Nine LNG-powered Vessels

2024-03-18 - Venture Global plans to deliver the vessels, which are currently under construction in South Korea, starting later this year.