For decades, the wide countryside north of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex concealed a sleeping giant of a gas field. The thick, pervasive Barnett Shale was well known to local geologists-the Mississippian-age formation is a rich, organic shale that had sourced many of the conventional accumulations in and around the Fort Worth Basin. But, it was tight as a tombstone. Most everyone considered it hopeless as a potential reservoir.

Mitchell Energy & Development Corp., however, believed in the shale. It spent two decades patiently experimenting with the Barnett, plying the recalcitrant reservoir with the latest engineering advances. The Woodlands, Texas-based independent was astonishingly successful. Today, Newark East Field is one of the very largest gas fields in Texas, producing more than 400 million cubic feet per day from more than 900 wells. And farsighted Mitchell owned most of it.

In January, Mitchell was merged into Oklahoma City-based Devon Energy Corp. in a deal valued at $3.5 billion. Devon gained 2.5 trillion cubic feet equivalent (Tcfe) of proved gas reserves, almost 300,000 net acres of undeveloped land, 9,000 miles of pipelines and six gas-processing plants, entirely in Texas. The Barnett Shale alone accounted for 2.1 Tcfe of Mitchell's proven reserves. Moreover, it appears that the Barnett Shale still offers generous growth potential.

"It's truly phenomenal in its nature. I predict that our grandchildren will be unlocking the vast reserves and producing significant quantities of Barnett Shale gas for years and years to come," says Rick Clark, Devon Energy vice president, Permian-Midcontinent division.

Devon sees the Barnett as a unique, unconventional gas resource that provides both low-risk development growth in production and reserves and long-term growth potential through exploration and future technical advances.

The play's history

The Barnett's transition from a source rock to a commercial reservoir is a story of time, money and patience.

From the early 1950s until the rise of the Barnett play, drilling in the Fort Worth Basin had focused on the 2,000-foot-thick Boonsville Bend conglomerate, a shallower Pennsylvanian formation. The Barnett was the source rock for these overlying clastic reservoirs, which have produced more than 2 Tcf of gas.

As those reservoirs matured and opportunities for further exploitation withered, attention turned to the Barnett. The shale is ubiquitous throughout the Fort Worth Basin, covering a 4,200-square-mile area. It ranges in thickness from about 200 feet in Parker and Jack counties to about 900 feet right against the Muenster Arch, which trends northwest-southeast through Denton County.

In the most active area of drilling-eastern Wise, western Denton and northern Tarrant counties-the Barnett occurs at the relatively shallow depths of 6,500 to 8,500 feet, and attains an average thickness of about 450 feet. In core, it looks like a first cousin to blackboard slate, and about as permeable. Clearly, engineering would be the key to unclench the Barnett's potential.

Mitchell discovered Newark East Field with its C.W. Slay #1 in 1981. From then until 1997, wells were fractured with massive hydraulic stimulations, using very viscous, gelled fluids and as much as 1.5 million pounds of sand for proppant.

The pace of drilling was measured-only about 50 Barnett wells had been drilled in the entire play by 1989. Those early wells tended to peak at production of around 750,000 cubic feet of gas per day, before beginning the steep hyperbolic declines that are typical of stimulated shale-gas wells. Mitchell estimated its wells, prior to 1990, were completed for an average of $850,000 and recovered about 600 million cubic feet of gas each. Notably, the company could afford to experiment with the unconventional reservoir-until 1995, it held a gas contract that guaranteed very favorable prices.

In the mid-1990s, Mitchell began to develop Newark East Field on 40- to 50-acre spacing. In 1997, the company experimented with an innovative frac technique that was enjoying success in the Cotton Valley Sands in East Texas.

The water frac, also called a light-sand or slick-water frac, employs ungelled frac fluid and very low sand concentrations, injected at very high rates. Just 100,000 to 150,000 pounds of sand are used in a treatment, making a job far less costly than a massive-style frac.

Although pumping less sand can seem counterintuitive, operators believe the technique delivers excellent fracture lengths while minimizing fracture heights. The water frac is well suited to low-permeability reservoirs, which require extensive fractures to deliver commercial volumes of gas, but where costs must also be tightly controlled.

Better yet, the wells produce at stronger rates. Today's Newark East completions boast average peak rates of about 1.4 million cubic feet per day. Plus, the lower costs allow more intervals to be fraced. In many-but not all-parts of the field, the shale has an upper member and a lower member, separated by the Forestburg Lime. While older wells were stimulated in the Lower Barnett only, newer ones are completed in both the Upper and Lower Barnett.

Part of the reason the Barnett in the Newark East area responds so superbly to stimulations is that it is sandwiched between tight limestones in the Pennsylvanian Marble Falls and the Ordovician Viola. The limestones function as extremely effective frac barriers. The Viola is particularly important because it overlies the Ellenburger, which tends to produce salt water. A Barnett well that produces water is a production nightmare; normally the wells make little or no water.

host thousands of additional wells.

"The key to the stimulation is finding the upper and lower boundaries and designing a job of the correct size," says Nick Steinsberger, Devon operations engineer. "The design length has a definite impact on the initial rates, and we want to get high rates in the first years of production." A water frac typically costs Devon about $100,000 to $125,000, about 60% less than the cost of a massive gelled frac.

The Newark East area

Devon currently has 800 Barnett wells and gross operated production of 345 million cubic feet per day, almost all in the 120,000-acre core Newark East Field. That core sits in the middle of a 435,000-acre area that is more lightly drilled, but where wells have encountered Barnett Shale similar to that in the proven area. Devon holds some 90,000 acres in the core area and another 140,000 acres in the expansion area.

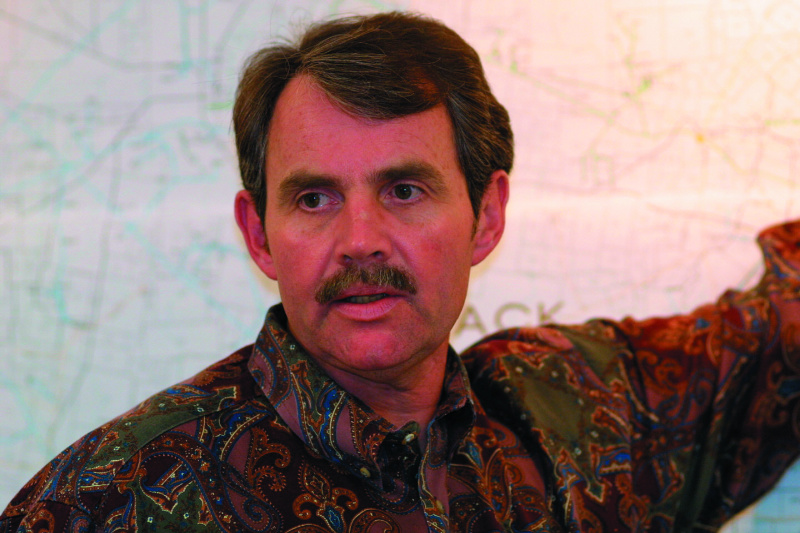

Steinsberger,

Devon engineer,

says the correct

design length is

crucial to proper

fracture

stimulation in the

Barnett Shale.

At press time, Devon was running 18 drilling rigs; in 2001, it drilled 321 Barnett Shale wells. It can maintain that pace for years, as it holds 1,100 additional locations in the core area alone.

Going forward, the company estimates its capital costs at approximately $750,000 per well, with each well recovering 1.25 billion cubic feet of gas (Bcf). "In our economics, we cut off the average life for a Barnett well at 25 years, but these wellbores will actually be producing much longer," says Mark Whitley, Devon's production and operations manager for the Fort Worth Basin. "The most important time is the first five years, because that's when we make most of the gas."

Devon can drill and complete Barnett wells for an average finding cost of 60 cents per thousand cubic feet, a figure that explains why the company continues its brisk activity even in these times of soft gas prices.

An endeavor that is even more economic than drilling new wells has turned out to be the refracturing of existing ones. Wells that were completed with the old-style massive gelled fracs respond extraordinarily to a water frac, often regaining peak production rates close to that of a new well. To date, the company has refraced 180 wells, and still has an additional 200 such treatments slated for this year. "On average, we have added new reserves of 700 million cubic feet per well, for a cost of $300,000 each," says Whitley. "Our finding and development costs for a refrac are about 45 cents per thousand cubic feet."

This ability to come back to a well after several years of production and recapture or improve its rate and its reserves is one of the marvelous features of the Barnett play. Apparently, after depletion has reduced the pressure around the wellbore, a subsequent stimulation establishes new fracture networks.

The future holds another possibility as well. To date, Newark East has been developed on 55-acre spacing, but Devon has six pilots under way to investigate downspacing to 27 acres.

"We have learned over the years that we can't look at just one area. We deal in averages in everything we do in the Barnett," says Whitley. Therefore, the pilots are placed in areas with various productive characteristics-dry gas, rich gas, excellent producers, average producers. "We don't know yet if we will be able to downspace all the field or a portion of the field, but in either case it could mean thousands of additional wells."

Even with the best application of current technology, only about 8% of the 147 Bcfe of gas-in-place per square mile is recovered from the Barnett Shale, he says. "We have a huge target here for the future."

Indeed, in 1998 the United States Geological Survey independently estimated the Barnett Shale play contained technically recoverable gas resources of 10 Tcf; to date, less than one-quarter of that volume has been developed.

Gas gathering and processing is another facet of the play. Throughout the northern half of Newark East Field, the gas is quite rich in condensate, while the southern portion yields dry gas.

In the wet-gas area, Devon gathers both its own and third-party gas and sends it to its Bridgeport, Texas, plant for processing. Presently, the plant can handle 450 million cubic feet per day, and Devon plans to expand that to 620 million cubic feet this year. The midstream assets add revenue to Devon's upstream operations, allowing it to take full advantage of the rich Barnett gas. The integration of the businesses also guarantees multiple pipeline interconnects, on-system markets and firm transportation for Devon's gas.

For decades, the only outlet for the basin's gas was a pipeline that could carry about 150 million cubic feet per day to Chicago. Last fall, the Chicago line was to be upgraded to carry 200 million per day, but that expansion has run into delays. (At press time, the project was not completed.) The remainder of the basin's production was sold to local markets for power generation and home heating, and the demand was very weather-dependent.

The picture for the basin changed with the construction of a 24-inch pipeline to carry gas from the Bridgeport plant south to interconnect with two 36-inch intrastate pipelines. Devon now can send 360 million cubic feet per day through this pipe, which has added greatly to its marketing options.

Additionally, the company recently looped a line and added compression in the southern, dry-gas portion of the field. The expanded capacity connects directly to pipelines that serve the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex markets.

A competitive field

The combination of a low-risk play with reasonable drilling and completion costs attracted industry attention, and many companies became intrigued with the Barnett play. Some secured positions in the highly sought after core area; others have concentrated their efforts in the expansion area.

The play even has enough sizzle to interest a player as large as Burlington Resources. The company has been active in the Decatur area, in Wise County on the northern side of Newark East. Burlington has 4,000 acres on which it holds deep rights, and has drilled eight wells to date. "We began drilling in late October, and we have been running one rig continuously," says Bill Bolla, Burlington's Midland-based Midcontinent division exploration manager.

The company has completed six wells and tied four of those into a pipeline. So far, it likes what it sees. The engineering aspects of the Barnett appeal to Burlington-it prides itself on its drilling and completion expertise. "We're trying some new things-we're approaching the stimulations with some different ideas. We've had some interesting results early on, and we're encouraged by that." Incidentally, Devon is a partner in the Burlington acreage, holding a 25% working interest.

"Lower prices could slow the growth of the play in the near term, but the resource exists across a very large area. We stand by the long-term fundamentals of natural gas and hope to expand our position in this area," says Bolla.

A smaller firm that is quite active in and around the core area is Dallas-based Chief Oil & Gas LLC. Chief was founded in 1994 to exploit undeveloped reserves in North Texas, specifically in the Fort Worth Basin. Initially it concentrated on drilling Boonsville Bend conglomerate reservoirs, successfully completing some 35 wells. As it become apparent the Barnett was overtaking the basin's other plays in size, reserves and productive capability, Chief became intrigued. It drilled its first well in the fall of 1997.

Jones, president

Of Chief Oil &

Gas, says the

Barnett Shale

has overtaken all

of the other plays

in the Fort Worth

Basin in size

reserves and

productive

capability.

The firm concentrated on leasing in an area where it believed the field was most likely to extend. It has accumulated 10,000 acres in northwestern Tarrant County and 6,000 in Denton County, and has drilled 42 wells. Presently, Chief is running a rig in each area. "We fund our drilling through investors, internal cash flow and bank debt," says Trevor Rees-Jones, president.

The Barnett has been good to Chief-during the last two years, the company's production has grown from around 4 million to 20 million cubic feet per day. "Based on what we know at present, we have at least 150 locations left to drill, and potentially more than 300."

Chief believes that identifying fractures is crucial to making a commercial well. "We run specialized logging suites to identify sweet spots in the Barnett Shale," says Tony Carvalho, manager of geology. "What we are looking for is how well the rock is fractured." The number of fractures identified by the logs is a broad indication of how a well will perform after stimulation, but it's not the whole story-sometimes the Barnett delivers surprises.

Initially, the company concentrated on developing its Denton County position, where it still has another 50 locations to drill. The Tarrant County holdings are now taking center stage, however.

Tarrant County poses special challenges for the operator. Wells there are prolific, producing dry gas at rates up to 1.5 million cubic feet per day. But, Chief is bumping into the city limits of Fort Worth. (See sidebar.)

Due to the amount of present and planned development, Chief often agrees to predetermined well locations and road and pipeline placements when it takes a lease. This way, the landowner is comfortable with exactly where the land will be affected. If it makes business sense, the company will also buy surface rights for a location on the urban fringes. Because of the surface restrictions, Chief expects that about one-third of its Tarrant County wells will have to be directionally drilled.

plans to be quite

active in

northwestern

Tarrant County,

says Tony

Carvalho,

manager of

geology.

"Many people in Tarrant County think they are going to sell their land for $10,000 to $20,000 an acre because everybody is going to come in and build houses," says Cliff Thomson, operations and engineering vice president. The landowners want the smallest possible location for a well, but an operator must have enough room to allow for subsequent fracture stimulations.

Chief can squeeze a one-well location down to close to an acre after drilling and completion, if a water source for future fracs is available. If it needs to use frac tanks-50 to 60 of these might be required for a water frac-the location will require at least three acres. "This will be an active area for a long time, and we need to have adequate access."

Another hurdle in the Tarrant County area is gas marketing. The county doesn't yet have infrastructure, and the dry-gas pipelines that would take gas from that area are already close to capacity. Chief is investigating several options, however, and expects to have a solution shortly.

The scenario is much more established in Denton County. In 1996, the firm negotiated a contract that covered all of its production. Bottlenecks are still a problem, however, because so much gas is being brought to market from the area.

An independent that has long been established in the Barnett play is Dallas Production Inc., the operating company of Pitts Oil Inc. The firm controls 35,000 acres in Wise and Denton counties, and during the past two years has drilled 70 wells. In the early 1980s, Dallas Production drilled several Barnett wells with Mitchell on some jointly owned acreage. It didn't become really active until the late 1990s, however, after water-frac techniques reduced costs.

At present, the company plans to restrict its new drilling to leases with drainage problems or short-term obligations. It will focus instead on doing remedial work on its existing wells, which are in the gas-condensate area. "We've had problems all fall with pipeline shutdowns, and because of that our wells have loaded up," says David Martineau, exploration manager. Through an affiliate, the company owns two 10,000-foot drilling rigs, which it will put to work for third parties.

working in and

around Fort

Worth's city

limits include

squeezing

locations into the

smallest possible

area, notes Cliff

Thomson, vice

president of

operations.

"We have a lot of acreage, and we will continue to be active in the play. But, unless gas prices go up or unless drilling and service prices start to come down, the Barnett play cannot be sustained at $2 gas prices," he says.

Threshold Development Co., another local operator, owns a prime position in the heart of Newark East. The Fort Worth company holds approximately 6,000 acres in the southeastern Wise County and northeastern Tarrant County. Threshold is a family firm, started by Johnny Vinson in 1971 and currently run by his son Bud, president since 1987.

Currently, the firm is drilling its twelfth well in the Barnett Shale. It has been running a rig steadily since last August, and plans to continue at that pace. Threshold prides itself on being an efficient, cost-effective operator, and it is looking to expand its holdings in the Barnett Shale. In addition to its Barnett properties, Threshold has interests in the Permian and Delaware basins and in Mississippi.

Barnett frontiers

Although Newark East Field and its expansion area cover an amazing amount of countryside, these account for mere percentages of the Barnett's total extent. The wider reaches of the play have also generated enthusiasm.

The present boundaries of the productive Barnett are defined on the south by the city of Fort Worth; on the east the Muenster Arch and Ouachita Front; on the north by a phase change to oil; and on the west, by the pinchout of the Viola. Operators are pushing against these limits, and are particularly keen on expansions to the west and south.

How can an explorationist focus down on a prospective area? A quick survey of the Barnett might lead observers to the conclusion that it is a gas-farming project, just a matter of plunking down rigs and lining up frac trucks. That is far from reality, however. The Barnett has its own peculiarities and mysteries, and like most reservoirs refuses to behave in a standard manner.

Geochemistry is a crucial aspect of the play. "The Barnett is a source rock that has become a reservoir in its own right," says Dan Jarvie, president of Humble Geochemical, a service firm based in Humble, Texas.

Through time, the Barnett has undergone several cycles of very deep burial and uplift. The rock generated oil, expelled it and resealed itself during these episodes, though like most thick shales it was not very effective at expelling.

As the rock cycled through these episodes, it was fractured in the primary generation phase, and then again when the oil cracked to gas. The microfractures caused by the cycles of hydrocarbon generation and oil cracking were filled enough to allow production of gas, although now the rocks are cold and do not actively generate hydrocarbons.

When operators relate the thermal maturity to information on the Barnett's composition, they can predict the areas that are most likely to have dry gas, wet gas or oil. Some companies, such as Devon, seek out the wet-gas areas; others would rather find dry gas; some seek to avoid the oil window.

"Geochemistry looks at what is in the rock; other tools are indirect. It identifies sweet spots," says Jarvie.

Another factor to consider is the variable lithology of the Barnett. It appears that the composition of the rock has an effect on the amount of natural fracturing, says Floyd "Bo" Henk, a McKinney, Texas-based consulting geologist with The Pacheron Group.

Henk's specialty is reservoir description. "The Barnett was deposited on a ramp/deep-shelf setting within an incipient foreland basin in a restricted anoxic system. In general, it's a finely laminated, organic-rich black shale comprised of mixed-layer illite/smectite clays. Interbedded with these organic-rich shales are carbonates and chert, found in varying amounts across the basin. Apparently, a good amount of carbonate debris came into the system, probably on storm-event beds in the form of sediment gravity flows."

Chert is a vital component. "The Barnett has some silicified members, primarily composed of sponge spicules. That's probably the part of the formation that is fracturing. The higher the silica content and chert content, the more likely that the shale will have natural fractures and be a good candidate for induced fractures with a lower frac gradient."

Explorationists also need to locate areas of good natural fracturing. Some firms chase basement linements, while others look for areas of karsting and collapsing of the underlying Ellenburger. Seismic, where available, can be helpful. Interestingly, very close proximity to faults or shear zones seems to be detrimental to production, at least in the areas that have been developed to date.

"Eventually, the Barnett could be one giant gas field, with some areas producing better than others. Whether the better wells are found in areas of thicker isopach with more chert and less carbonate, we don't know yet. We also don't know the exact role that karsting and maturation are playing in the production," says Henk. "We're still learning a lot about the play."

Many companies are intrigued with pushing the play to the west past the Viola subcrop, which runs roughly north-south through the middles of Wise and Johnson counties. Success has been stymied in this part of the Barnett by the absence of the Viola limestone. Without that bottom seal, the stimulations tend to travel down into the Ellenburger and bring on copious amounts of water.

Devon holds more than 100,000 acres in Parker and western Wise counties, much of it held-by-production from the shallower Bend conglomerate fields. It and several other operators are intent on solving this engineering puzzle. Ideas include varying the frac designs; drilling only a couple of hundred feet into the Lower Barnett and then fracing; employing an artificial frac seal; or drilling horizontal wells.

Quite a few firms are also interested in skipping over the city of Fort Worth and expanding the play to the south, particularly into Johnson County. Although the county is very lightly explored, its geology appears very similar to that in the Newark East area.

Devon holds 90,000 acres in central and eastern Johnson County and plans to drill several exploratory wells there this year. Most of its acreage is east of the Viola subcrop, so it has bottom seal.

Adexco Production Co., a Fort Worth-based independent, has assembled more than 40,000 net acres, mainly in southern Johnson, northern Hill, northern Bosque and eastern Somervell counties. The company first took a regional look at the play, using source-rock geochemistry in addition to all the available subsurface data.

"We studied a 15-county area, and we believe that there is potential for another Newark East Field in the Barnett," says Craig Adams, vice president. "We like the Barnett because it is a repeatable play. The high-graded fairway does not have the conventional risks of reservoir, source, trap, seal and charge failure. Gas charge has been proven over a multi-county area, and additional drilling will be required to find new sweet spots outside of Newark East Field."

About half of Adexco's acreage has the Viola bottom seal beneath it, but the company believes the details of the local geology are more critical to success. "There are areas where the Viola is wet, and areas where the Ellenburger is tight. The frac technique that works in Newark Field may not be the technique that ultimately proves to be effective in other areas." Adexco is seeking partners to help it with evaluation and development of its acreage block; it also has a small position in northern Tarrant County.

Another player intrigued with the southern area is Burlington Resources. In addition to its Wise County leases, Burlington has a 30,000-acre contiguous block in Bosque County. It plans to drill its first Barnett well on the leases by midyear.

"A few wells have been drilled down there, but most of them have not been successful," says Bolla. "It comes down to the completion and the ability to keep the water out." The bottom seal is not present in that area, so the fracs have to be designed accordingly. "It always comes back to how much it costs to get a given volume of gas."

Finally, the productive area could potentially be expanded to the north and northwest. Here, the Barnett enters the oil window, and because it is so tight, its relative permeability to oil is quite low. As yet, companies are still struggling to produce commercial rates in this area. Some are trying such techniques as submersible pumps. If successful, the prospects are vast: the Barnett continues up into Montague and Clay counties and almost into Wichita Falls.

So, keep an eye on the Barnett. It's a reliable producer that already covers an astounding area, and it will certainly weather this time of low gas prices and come roaring back. Perseverance created the initial play, and many firms plan to persevere in their attempts to extend its boundaries.

Recommended Reading

Exxon Versus Chevron: The Fight for Hess’ 30% Guyana Interest

2024-03-04 - Chevron's plan to buy Hess Corp. and assume a 30% foothold in Guyana has been complicated by Exxon Mobil and CNOOC's claims that they have the right of first refusal for the interest.

Exxon Ups Mammoth Offshore Guyana Production by Another 100,000 bbl/d

2024-04-15 - Exxon Mobil, which took a final investment decision on its Whiptail development on April 12, now estimates its six offshore Guyana projects will average gross production of 1.3 MMbbl/d by 2027.

Exxon Mobil Green-lights $12.7B Whiptail Project Offshore Guyana

2024-04-12 - Exxon Mobil’s sixth development in the Stabroek Block will add 250,000 bbl/d capacity when it starts production in 2027.

Pitts: Heavyweight Battle Brewing Between US Supermajors in South America

2024-04-09 - Exxon Mobil took the first swing in defense of its right of first refusal for Hess' interest in Guyana's Stabroek Block, but Chevron isn't backing down.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Americas

2024-04-23 - The final part of Hart Energy E&P’s Deepwater Roundup focuses on projects coming online in the Americas from 2023 until the end of the decade.