The Port of Bayonne, N.J., is a petroleum products hub. It’s showing growth after years of decline and now has the ability to handle larger vessels. The facility hopes to export crude oil in the near future. Newark Liberty International Airport lies in the distance at upper right. Source: International Liquid Terminals Association

Many experts agree that the future of America’s oil and gas industry will be determined by export terminals designed to reduce the glut of fossil fuels unleashed by the shale revolution, ultimately providing price stability.

Time is essential in exporting LNG as markets, especially China and India, seek to meet growing energy demand while using less coal. Though there is a currently large excess natural gas supply, that excess is expected to decline within five years, Reuters reported.

In the news

Exports are in the news. Headlines this year include:

-

Plans advance for a Marcellus LNG export facility to be built on property owned by Philadelphia Gas Works.

-

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reports effects of the proposed Jordan Cove LNG terminal and 230-mile feeder pipeline would be “short term or on a small scale and dispersed broadly across 250 miles.” The controversial project in southern Oregon would be the first petroleum export terminal on the West Coast, but it faces federal, state and local challenges.

-

Sempra Energy and Saudi Aramco subsidiaries sign Interim Project Participation Agreement for the multibilliondollar Port Arthur LNG export project under development in southeast Texas. Sempra plans to develop five “strategically located” LNG projects in North America.

-

Enterprise Products Partners LP and Navigator Holdings Ltd. export the first cargo consisting of 25 million pounds of ethylene to Japan from their jointly held marine terminal along the Houston Ship Channel.

-

New York-based New Fortress Energy LLC receives an $800 million loan to fund LNG terminals and infrastructure in northern Pennsylvania to be connected to an export pier that they will build on the Delaware River.

-

Sixteen states announce opposition to administration proposal to transport LNG by rail, citing safety concerns.

-

Kinder Morgan Inc. asks federal regulators for approval to put a fourth liquefaction train in service at its $2 billion Elba Island LNG export terminal in Georgia. The first export cargo from Elba left in December 2019. And in late 2019:

-

Cheniere Energy Inc., the leading LNG producer and exporter in the U.S., receives approval for its Corpus Christi Stage 3 expansion, which includes seven midscale liquefaction trains.

-

Tellurian Inc., led by former Cheniere executives, receives approval for site preparation for its big Driftwood LNG export terminal in Louisiana. Construction should begin this year with first production in 2023. The project includes a 625-mile, 42-inch pipeline from Waha Hub in West Texas to the Lake Charles area. Purchase memoranda of understanding have been made with France’s Total S.A. and India’s Petronet LNG Ltd. Financing is to be completed this year.

Impressive numbers

Domestic LNG exports have approached 7 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d), making the U.S. the world’s third largest LNG exporter in barely three years, trailing Qatar and Australia. The International Energy Agency predicts the U.S. will add 30% of global gas production through 2030 and could reign as the largest exporter by 2025.

Including projects under construction, U.S. LNG export capacity is expected to reach 9.6 Bcf/d this year and 10.3 Bcf/d in 2021, from 7.6 Bcf/d in January. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Energy granted 11 new long-term LNG export approvals, including two under the new small-scale export rule. Meanwhile, two new large-scale terminals came online along the Gulf Coast, and the U.S. now exports two cargos of LNG almost daily. When the first wave of projects is built out, exports may reach 60 to 70 million tons of LNG per year.

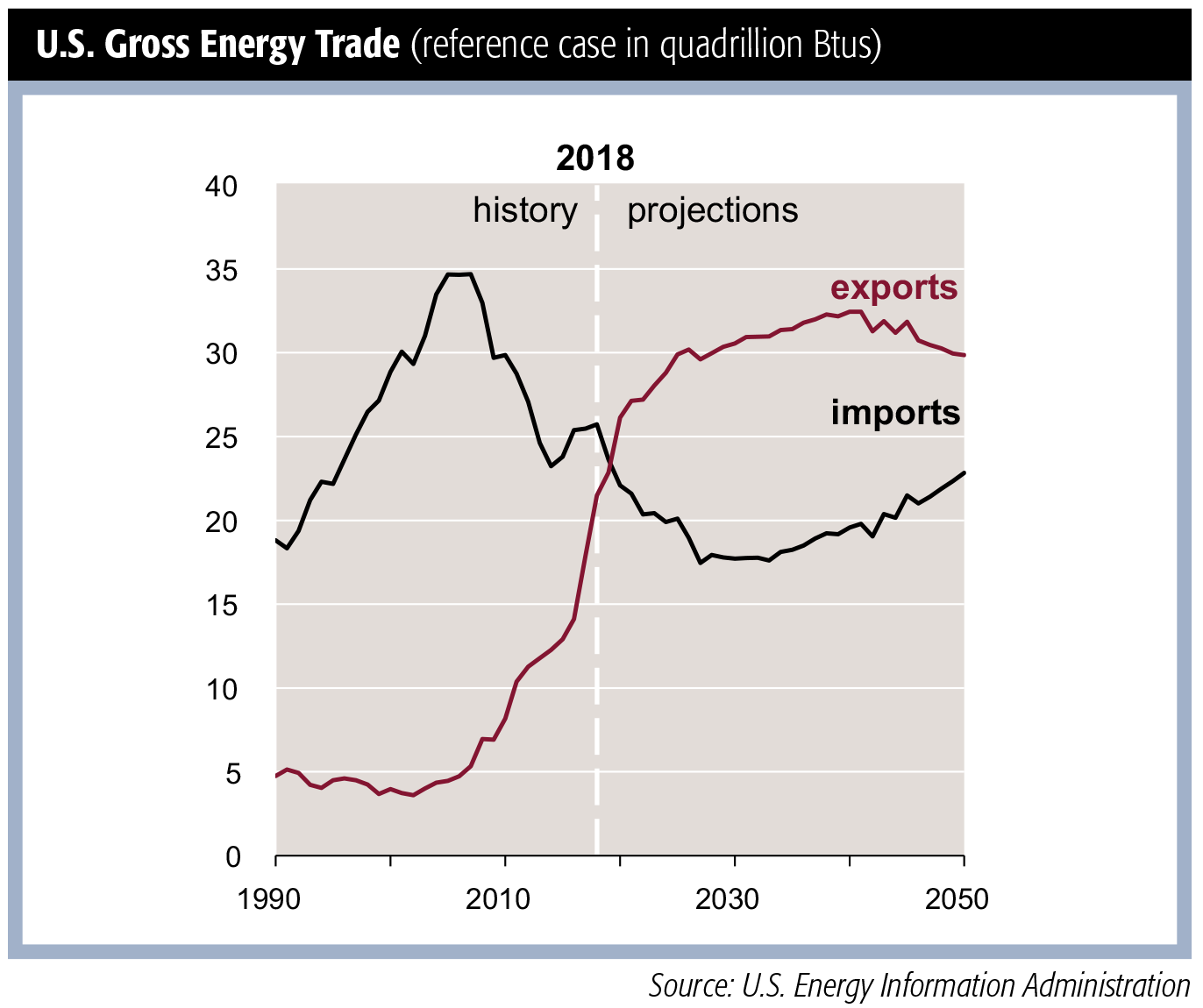

In September 2019, the U.S. exported 89,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) more petroleum—crude oil and refined products combined—than it imported, the first month this happened since monthly records began in 1973.

Crude oil exports are the largest contributor to U.S. petroleum export growth, from 591,000 bbl/d in 2016 to 2.8 million bbl/d in 2019.

With this in mind, the Trump administration wants to revise the National Environmental Policy Act to ease permitting by removing “cumulative impact,” or climate change, as a consideration for national infrastructure projects such as natural gas pipelines. Reviews would be limited to two years and disputes quickly settled.

Credit shale

“It’s development of the Permian Basin and all of the shale plays around the country. Bulk exports through Houston and Corpus Christi [Texas] are seeing a significant surge as well as liquefied petroleum gas [LPG] terminals resulting from the rise in drilling activity and liquids and NGL production,” Jason Feer, global manager of business intelligence for Poten & Partners Inc., a Houston-based energy and ship brokerage, told Midstream Business.

Kathryn Clay, president and CEO of the International Liquid Terminals Association, told Midstream Business that she agrees.

“It’s all very connected to the shale oil/gas revolution and resulting boom in production that hydraulic fracturing unleashed, increasing production beyond domestic demand and leading to the oil export ban being lifted in December 2015. On top of that, our refining infrastructure is set up for heavier crude than the light, sweet crude that comes especially from the Permian.

“The best alternative has been to export that sweet crude, which Europe has historically been better able to handle. Asian markets are also retweaking their plants to accommodate lighter crude,” she added.

Feer said sweet crude production has been declining in the North Sea and West Africa. It pays to export the product because it sells for a higher price and is in more demand internationally while the nation continues to import Mexican and Middle Eastern heavy and medium sours, which U.S. refineries can easily handle.

Terminal timing

Clay detailed why terminals are essential to the export process.

“You can’t import or export liquids without a set of terminals in place. From a pipeline to a vessel, you must have a terminal there; the alternative is a logistical nightmare. The economics of commodities are changing. You can’t ensure that your pipeline shipment is exactly coordinated with the arrival of a ship because those oceangoing vessels have a 48-hour window—in the best cases—when they’re likely to arrive. There are also cases where people will store the fuel, not because they can’t sell it, but they’re hedging for economic reasons.”

Also driving demand for sweet crude in Europe and Asia is the new International Maritime Organization 2020 rule that requires global shipping vessels to use low-sulfur diesel as a fuel.

Yet the growth of terminals has been “stepwise” until recently because there seemed to be little need for change, Clay said.

“It’s not a question anymore that we’ll have to build new export terminals as we’ll run out of the ability to expand existing terminals. In the last 18 months, you’re seeing a lot of announcements of intended development of new export facilities. Almost anyone would tell you that they will not all be built; we are starting to see a shake-out.”

Different products, different challenges

Feer said developers face different challenges depending on what they’re marketing: oil, LPG or natural gas.

“The payback periods for petroleum projects tend to be a lot shorter, and the technology is simpler: pipelines, tanks, loading buoys, etc. Most are not project financed, so companies pay from their own equity resources. They make a call or judgment on what demand and production are going to be. Today the U.S. can’t absorb any more LPG or sweet crude, so you have to export.”

It’s not a hard judgment for terminal operators and producers, he added.

“With LNG, it’s different orders of magnitude in terms of the investment required. A cheap LNG train would be $2 to $3 billion, and developers on the Gulf Coast have been essentially startups. Cheniere, Cameron didn’t have big balance sheets, so they had to project finance.

“In order to project finance something that involves that kind of investment, they had to find people willing to sign long-term contracts, 20-years or so, so they could tell banks that ‘you’re going to loan us a couple billion dollars, and we’re selling LNG tolling services to these customers who are good for it; they’re creditworthy international oil companies or Asian or European utilities,’” Feer said.

Similarly, export terminals and would-be developers of terminals are essentially competing by courting the same producers, Clay said.

“Until they secure those commitments, there is going to be a slowdown in the buildout. I think the strategy I can safely say for all of them is they’re all working very hard to try to secure those contracts. They’re all trying to meet with their prospective clients to make those commitments.”

Feer added propane, used to make propylene, has seen a huge increase of exports from the U.S. “The Chinese have built propane dehydrator units as they are short of propylene. Particularly in China, there is strong growth in demand for LNG and natural gas; Southeast Asia, India to a lesser extent.”

Clay agreed China has been “the sink” for many global commodities. After the U.S.-China tariff war ends, she expects big increases in U.S. exports to China of crude, LPG and natural gas. In fact, many reports indicate that 2020 will be a record year for Chinese LNG imports. While energy demand is flat in Europe and Latin America, Canada remains a strong market because refiners are familiar with U.S. domestic grades of crude.

Big ships

Deeply concerning to Clay is the next round of investment necessary to build new export terminals, rather than expanding existing facilities. They must have the capacity to handle very large crude carriers (VLCCs). The Louisiana Offshore Oil Port in Louisiana is the only

U.S. port able to fully accommodate the vessels. Meanwhile, the rest of the world is moving ahead.

Certain other U.S. ports have been modified to handle VLCCs, but the big ships must be topped off at sea to be fully loaded due to their deep drafts.

“We need to invest in our ports and infrastructure so that they are modernized and competitive,” Clay continued. “That means building at least a subset of the planned terminals able to accommodate VLCCs. We used to have some of the largest ports in the world, but we’ve lost ground. As recently as 2002, we only had two of the top 10 largest ports in the world: Louisiana and Houston. Now eight of the top 10 are in China. The others are in South Korea and Saudi Arabia.

“It’s vital, not just for terminals and petroleum, but for our ability to participate in world trade, that we make these investments. Terminals are certainly an important part of that.

“Forgive the pun, but it’s quite a sea change in our port infrastructure and commerce,” Clay added.

At the end of 2019, pipeline giant Enbridge Inc. and Houston pipeline and export terminal operator Enterprise Products Partners announced a letter of intent to jointly develop a deepwater crude oil terminal in the Gulf of Mexico capable of fully loading VLCCs, centered on Enterprise’s Sea Port Oil Terminal.

However in a setback, last October the Carlyle Group quit a multinational effort for a $1 billion crude oil export terminal at Harbor Island in Corpus Christi. The Berry Group is now the sole owner and has indicated it plans to move ahead with the project, which would serve VLCCs once the Port of Corpus Christi is enlarged.

Patrick Long, director of Opportune LLP’s process & technology practice, told Midstream Business to expect more alliances, given the heavy capital-intensive requirements and long time needed for regulatory approval at all levels.

“Not all projects will make it. It’s natural for a company to want to look for a partnership to help offset some of the risk and financial burden, in exchange for giving up some of the upside. In the case of Enbridge and Enterprise, the companies operate where there is very little overlap of business. Therefore, it makes sense for a partnership and takes advantage of synergies to distribute product to end customers.”

He agreed with Clay that logistic companies must broaden and diversify their reach in the supply chain through the extension of crude export terminals.

“Based on the logistics typically ending on land, the companies are missing out on the ability to tap into the VLCCs. So, I feel this is more about extending the supply chain and tapping into new customers and distribution methods as anything else.

“Think about the advantages of going with a logistics provider that can provide multimodal transport of crude to lock in a larger netback for the producer. Therefore, export terminals provide a reach to VLCCs as a means to extend sales channels,” Long said.

Based on reports from shipping companies, there is an oversupply of VLCCs, which is another contributing factor.

“This has led to a fall in rates for transporting fuels. VLCCs provide a tremendous benefit and economy of scale for transporting supply and locking in a low per-unit cost. While not the main factor, it certainly contributes to help justify the business case. Excess shipping capacity will keep rates low and incent refiners to utilize this mode of transportation in order to transport feedstocks,” Long added.

Among the key export players he identified are Enterprise, Phillips 66, Trafigura, Enbridge and Energy Transfer LP.

“The initial projects appear to have the strongest backers where those companies are natural logistic/pipeline companies. Those companies have the expertise in large-scale infrastructure plays. Their strategies are to secure and lock in producers so that they will have a committed capacity upon completion of the project,” he said.

“The strategy is to extend the infrastructure and charge a tolling fee to shippers. With additional pipeline out to a VLCC, these logistics companies will extend their ability to collect a fee. They just need to maintain full capacity in order to justify the cost of the project.”

Looming challenges

Long defines some key challenges facing the petroleum export sector, such as uncertainty around regulations.

“While it seems inconceivable that the lifting of the [crude export] ban would be overturned, the domestic politics are less moderate these days. Future administrations may not be so draconian in overturning the decision; they may pass additional legislation to limit it.

“When export projects were initially proposed, written and approved internally, there were a set of economic assumptions made to support the project. By the time projects are completed, the world will have changed. Who would have thought that there would be this extreme tension in the Middle East? Who knows what that will do to prices in the long-term (short-term effects already being felt)? Domestic crude price drops provide challenges.

“On the flipside, considering the instability in the Middle East, U.S. domestic crude seems favorable, so long as companies can lock in stable supplies at a comparable price,” Long added.

Recommended Reading

Thanks to New Technologies Group, CNX Records 16th Consecutive Quarter of FCF

2024-01-26 - Despite exiting Adams Fork Project, CNX Resources expects 2024 to yield even greater cash flow.

Cheniere Energy Declares Quarterly Cash Dividend, Distribution

2024-01-26 - Cheniere’s quarterly cash dividend is payable on Feb. 23 to shareholders of record by Feb. 6.

Marathon Petroleum Sets 2024 Capex at $1.25 Billion

2024-01-30 - Marathon Petroleum Corp. eyes standalone capex at $1.25 billion in 2024, down 10% compared to $1.4 billion in 2023 as it focuses on cost reduction and margin enhancement projects.

Humble Midstream II, Quantum Capital Form Partnership for Infrastructure Projects

2024-01-30 - Humble Midstream II Partners and Quantum Capital Group’s partnership will promote a focus on energy transition infrastructure.

Hess Corp. Boosts Bakken Output, Drilling Ahead of Chevron Merger

2024-01-31 - Hess Corp. increased its drilling activity and output from the Bakken play of North Dakota during the fourth quarter, the E&P reported in its latest earnings.