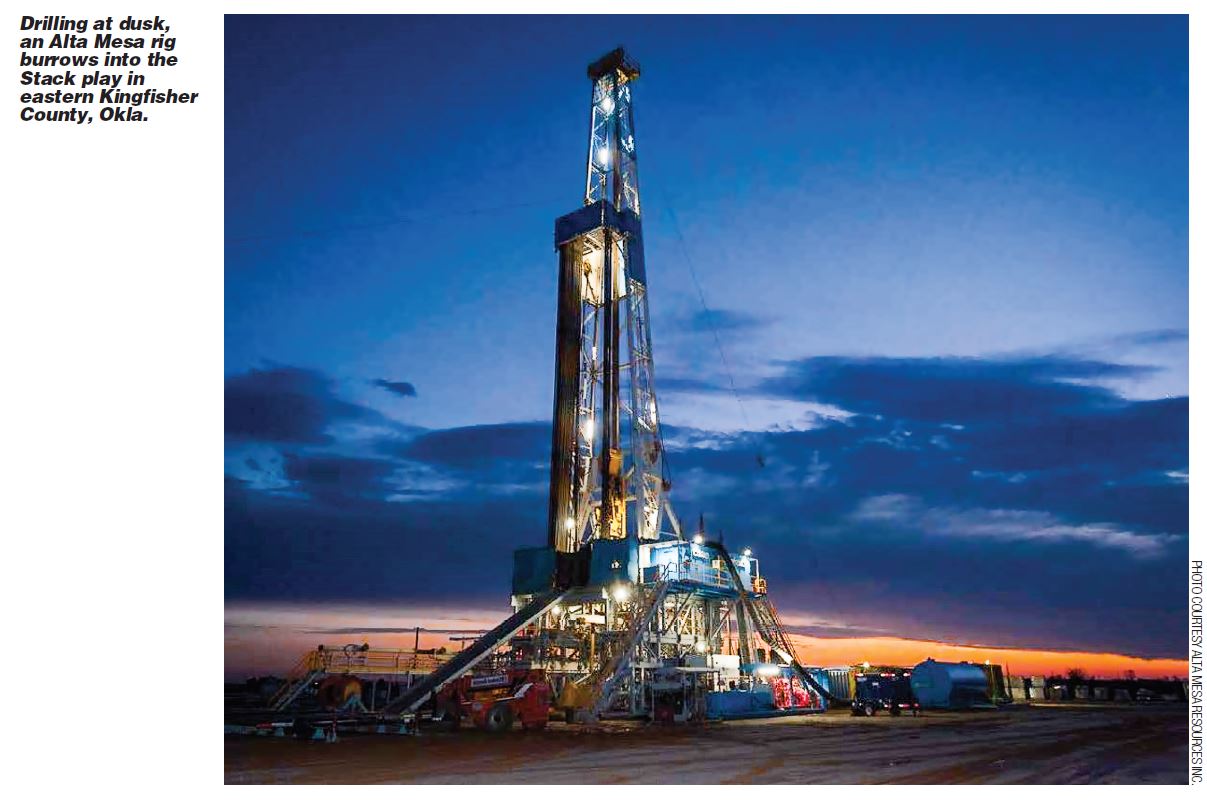

Alta Mesa Resources Inc. rolls out the first publicly traded Stack play company, a $3.8-billion enterprise with 130,000 net acres, $1 billion in liquidity and the leadership of Jim Hackett and Hal Chappelle.

The view from the top—captured by a hovering drone’s camera—lays out Alta Mesa Resources Inc.’s intricate operations near a gently bending river. The company has brought clean lines of orderliness, flattened smooth with use, to a wooded stretch of Oklahoma’s Stack play.

To Hal Chappelle, CEO, the picture conjures Richard Scarry’s children’s books—a mix of color and dutiful busy rabbits and police bears navigating airports and bus stations, offering children “a thousand things for their little eyes to see,” he said.

It turns out there’s a “Busy, Busy World” in Oklahoma’s Stack too.

Chappelle points out Alta Mesa’s surface impoundments for frack water, oil storage tanks, a horizontal well being drilled, a tank battery, vertical well, even the dividers—“they look great, right?”

“We had four rigs running, drilling a multiwell pattern at the same time,” he said.

VIDEO - View From The Top: Money, Midstream & Alta Mesa

Chappelle’s playground—and business—is changing now. He’ll now share control with other legendary oil and gas executives, and the company has gotten far more complex since early February.

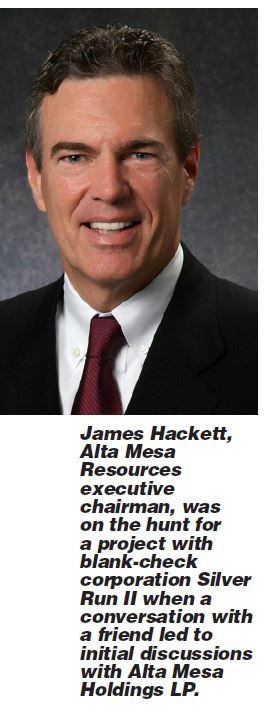

Chappelle’s Alta Mesa Holdings LP, Jim Hackett’s Silver Run Acquisition Corp. II and Kingfisher Midstream LLC combined to form the first publicly traded Stack pure-play company. The businesses report that, combined, they are worth $3.8 billion.

The “first” status isn’t particularly important to Chappelle, who credits work down by Newfield Exploration and Cimarex. The company’s vision is to have a portfolio of profitable and useful well projects with an ongoing 10-year horizon. First isn’t a part of the company’s mission statement.

“We’re really focused on being our best,” he said. “We recognize we’re on a journey. We didn’t arrive anywhere.”

The deal itself was about creating a unified upstream and midstream oil and gas manufacturer. Cash and stock from Silver Run II and funding from private-equity firm Riverstone Holdings LLC, which eclipsed $1.6 billion, will help its manufacturing machine hum.

The new Alta Mesa reigns over delineated Meramec and Osage—commonly lumped together as simply Mississippian age rock—and a 500-foot window of oil. The company’s leasehold spans Kingfisher, Garfield and Major counties, Okla., and holds more than 4,000 gross drilling locations. Alta Mesa is developing the naturally fractured formations as one large reservoir by creating conductivity among them, he said.

Its average production since the merger was announced in August has jumped 20% to 24,000 per day in February. It also boasts single-well rates of return of 80%, according to a January presentation. Returns exclude transportation fees and assume drilling and completion costs of about $3.5 million per well.

Kingfisher Midstream is intertwined throughout its operations with a gathering system now zigzagging more than 410 miles across the leasehold. With the start-up of a 200-million-cubic-foot-per-day (MMcf/d) plant expansion in first-quarter 2018, takeaway capacity has more than tripled to 260 MMcf/d from 60 MMcf/d in 2017.

With Silver Run’s involvement, the company achieves the capital it needs—from Silver Run and Riverstone—and an address on NASDAQ.

The combination isn’t the end game. As the merger was completed, Alta Mesa added 10,000 net acres and now holds more than 130,000 net. Kingfisher also significantly increased its infrastructure and gathering system.

“I think that the opportunity to combine the midstream and the upstream at this point in time …, it’s very fortuitous and I’m very, very pleased,” Chappelle said. “But I don’t know that I would say this is the culmination of anything. It’s just the next step.”

All stars

Two weeks after Alta Mesa’s stock debuted as AMR, Chappelle took the stage in Houston at Hart Energy’s inaugural DUG Executive conference.

Alta Mesa, Silver Run and Kingfisher are a triple-threat, bringing a balance sheet with heft, skill in the field and a midstream framework to carry product to market. The company will look to spin off Kingfisher, perhaps later this year.

“We’ve been able to move now into development mode,” Chappelle told conference attendees. He envisions shifting from four to six rigs to a “cadence of about 10 to 12” eventually. The company will grow during the next couple of years while adding debt before consistently operating in the black and returning cash to shareholders.

Alta Mesa crews perform simultaneous drilling of 10 horizontal Stack wells using four rigs north of the Cimarron River in eastern Kingfisher County, Okla.

It also has marquee names. Hackett—who retired as chairman, president and CEO of Anadarko Petroleum Corp., which named its headquarters “Hackett Tower”—is executive chairman.

Out of the gate, Alta Mesa has formidable balance-sheet strength. Alta Mesa and Kingfisher entered the combination with no outstanding borrowings under their credit facilities and a restated bank facility of up to $1 billion.

Alta Mesa Resources’ initial borrowing base is $350 million. Kingfisher is party to a $200-million facility. Alta Mesa’s held $565 million in net debt as of Sept. 30, with the bulk a $500-million bond.

Alta Mesa will now use its expertise to create and add value and “not just bring a checkbook, if you will,” Chappelle said.

Founder Mike Ellis oversees upstream operations as COO. Chappelle is president and CEO of the new company. In addition to his role as executive chairman, Hackett is COO of Kingfisher.

‘Magic connection’

Hackett’s name recognition and Riverstone’s backing helped Silver Run II complete a $1-billion blank-check IPO in March of 2017. The Permian, Appalachia, Powder River and other basins were all up for grabs.

Alta Mesa board member William McMullen, founder and managing partner of Bayou City Energy LP, knew Hackett and the two discussed Alta Mesa.

Hackett and Chappelle were acquaintances; they’d met. When they spoke in April or May of 2017 (accounts vary), the two men seemed to click.

“That’s the magic connection that was made, at that moment,” Chappelle said.

The two CEOs share a similar style, particularly when it comes to how to build and treat a team.

“I felt like Jim was somebody that we had a lot of symmetry with, when it came to underlying values of how you approach business, how you treat people and how you measure success,” Chappelle said.

Chappelle’s pride is clearly Alta Mesa’s people. When he talks about his employees, he puts them in this order: “scientists and engineers and businesspeople.” Inside Alta Mesa’s corporate offices, in Katy, Texas, the walls are covered with well logs, geosteering results and map after map. In one office, a geologist formerly with ExxonMobil Corp. runs six computer screens to monitor a well. In the same office, long imaging scrolls—a kind of underground MRI—are rolled out to study the fracking results.

The company’s geophysics, completions and fracking operations are headed by former leaders from companies such as Schlumberger—who in some cases have managed to bring their old teams over to Alta Mesa.

“Those are talents that are necessary to have a best-in-class operation,” he said.

Well recipes aren’t merely handed to a consultant. “We actually manage every single stage, every aspect of every stage, so that we tailor the proppant, the acid, the water, the fluid, the pumping rate—everything that we do here—so we can optimize each stage,” Chappelle said.

The bond among Alta Mesa’s staff members is strengthened by time; the team has been together through learning curves and growing pains.

“This is a company that came together and was grown together and created a learning curve together, that, at a critical point in our history, we decided we’d bring private equity in to be our financial partner,” Chappelle said. “So that’s a little different than what you see with a lot of the other private companies that have private-equity partners.”

Chappelle joined Alta Mesa in 2004, at a time when he was still skeptical of fracking and the Barnett and Marcellus shales. But after Alta Mesa Holdings spud its first horizontal well in December 2012—and had 13 under its belt in 2013—he was a convert of a kind.

Now he sees fracking as a rather straightforward “application of technology,” he said.

AfterChappelle and Hackett’s first conversation, the two men got to know each other over the next few months. Alta Mesa hadn’t been looking to make a deal with a special purpose acquisition company. The company had even explored its own IPO.

But in Chappelle’s view, Silver Run II’s most attractive piece was Hackett.

“Jim’s very, very important,” he said. “Then it really was a differentiated opportunity for us.”

While a deal was still a couple of months away, within a matter of weeks Chappelle said he “emotionally and philosophically” recognized the deal was worth pursuing. But a key piece remained—Kingfisher Midstream.

The triumvirate

On paper and in the field, Alta Mesa appeared destined to be a Midcontinent force. In land mass alone, its position is 20,000 acres shy of all the useable land in New York City and its boroughs.

It assembled a solid block in the Stack oil window. Its footprint compares favorably to E&Ps that operate on checkerboard positions.

About four years ago, Chappelle and others at Alta Mesa began to realize the potential the play offered. They also knew the aging infrastructure they’d built wouldn’t support the new production to come. Founded by Ellis in 1987, the company once held assets in the Eagle Ford area, the Austin Chalk, Weeks Island in Louisiana and Oklahoma.

After launching a horizontal well program in Oklahoma, Alta Mesa’s other areas were sold off. About 110,000 of Alta Mesa’s core Oklahoma acres are HBP. Chappelle said the company will be “thoughtful” about wells it drills on the remaining 20,000 acres in Blaine and Major counties, which have HBP obligations over the next three years. Alta Mesa Holdings’ infrastructure was less inviting, with legacy systems that were built around vertical production and 70-year-old technology.

“It became abundantly clear to us that the basin was functionally constrained for processing capacity, and the existing legacy processing capacity for gas was inefficient,” Chappelle said. “And there are contract attributes that were favored [for an] old style—you know, 50 years ago—kind of gas market and not the current” market.

ARM Energy took the lead in building a midstream system, funded in part by one of Alta Mesa’s private-equity partners, Highbridge Principal Strategies LLC. Kingfisher Midstream developed in tandem with Alta Mesa. Lines increased to 6-inchs from 2-inches and modern processing was added, including ethane rejection to produce propane.

“Highbridge came in to provide the financial strength and girth to build that,” Chappelle said.

He and Hackett agreed in their first conversation that the ideal enterprise would combine it all—upstream operations, midstream and money.

Hackett “wanted to combine both the upstream and midstream, something that I always felt was a very good combination,” Chappelle said. “His previous experience in the midstream certainly brought differentiated executive capability to this enterprise.”

Within a couple of days of speaking to Chappelle, Hackett was chatting with ARM Energy CEO Zach Lee.

Based in Houston, ARM agreed to sell Kingfisher Midstream to Silver Run for up to $1.55 billion. The deal included $800 million in cash, $550 million worth of Silver Run shares and up to $200 million in additional stock based on performance.

Lee said an in-depth analysis of the Stack play identified it as a successful region and would be profitable well before the area gained momentum with the greater midstream market.

“The Kingfisher system is galvanizing interest from numerous producers in the Stack play that understand and appreciate the value the system brings to their businesses,” he said.

Alta Mesa is Kingfisher’s biggest customer, which along with five other producers that dedicated about 300,000 acres to the system.

Chappelle said the infrastructure alleviates any takeaway worries that have hobbled other basins.

“For want of capital, we would have built this ourselves a few years ago due to the growing functional constraints and inherent inefficiencies of older legacy processing and gathering,” he said, adding that he was concerned “this basin might experience periodic near-term limitations to residue gas takeaway, particularly to interstate markets.”

“In addition to the gas that’s already hooked up to the legacy midstream operators, we now have this 60-million-a-day plant with a large gathering system, great compression, the right size of everything, and it’s being extended to 260 million cubic feet per day,” Chappelle said.

Triple crown

Alta Mesa’s Stack acreage was once populated by hundreds of vertical wells. In its initial area of operation, the company identified 125 active operators in a single township alone.

Its territory began to overtake the area—now covering about 300 square miles. The position is bisected by the border of Kingfisher and Garfield counties. The company operates fewer than 60 miles from Cushing, Okla., with a team that has worked in the Sooner Trend for a quarter-century.

With wells named after thoroughbred racehorses and brands of scotch, Chappelle said economics, not the size of the positioning over what the company acquires. That philosophy won’t change as the company adds new faces and partners or faces competitors.

By the end of 2014, the team had more than 44,500 net acres under its feet. The company began to aggressively lease and deal for Stack acreage. During each of the next three years, it added an annual average of 28,500 net acres to its footprint.

While some analysts have said land in the large Stack play is generally sewn up, Chappelle sees room for expansion in the broader northwest Stack area. That includes a sizeable amount of acreage “that is likely to change hands in the next couple of years,” he said

Alta Mesa essentially starts fresh, with near zero debt and money to buy, though acquisitions will still meet the same standards.

Over time, the company may push its boundaries outward or just take small tracts of leasehold, but it won’t chase anything outside of its comfort zone.

“There are material M&A opportunities that are going to present themselves in this general region,” he said. “And we believe we’re positioned to consider and compete to potentially be the best solution. We could do one or more, we could do none. We like building out from where we are because incrementally we have confidence in the next thing we’re doing.” Acquisitions are likely to be bolt-ons, Chappelle said. “At some point, there’s a saturation point, right? Where positions are pretty well-established.”

But not yet. And that means Alta Mesa will still be hunting for 50 acres here, 500 acres there, “all the time,” Chapelle said.

Chappelle isn’t averse to the small stuff, since that’s how Alta Mesa was built. “You’ve got to do a lot of blue-collar block-and-tackle stuff in the middle of that,” he said.

Alta Mesa’s healthy bank account and access to public markets now puts larger acquisitions within reach, but with the quality it seeks as elusive as ever.

West of Crescent, Okla., drilling proceeds on a horizontal Stack well in the heart of Alta Mesa's eastern Kingfisher County acreage.

Recommended Reading

US Raises Crude Production Growth Forecast for 2024

2024-03-12 - U.S. crude oil production will rise by 260,000 bbl/d to 13.19 MMbbl/d this year, the EIA said in its Short-Term Energy Outlook.

To Dawson: EOG, SM Energy, More Aim to Push Midland Heat Map North

2024-02-22 - SM Energy joined Birch Operations, EOG Resources and Callon Petroleum in applying the newest D&C intel to areas north of Midland and Martin counties.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for Fourth Week in a Row-Baker Hughes

2024-04-12 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by three to 617 in the week to April 12, the lowest since November.

Exxon Versus Chevron: The Fight for Hess’ 30% Guyana Interest

2024-03-04 - Chevron's plan to buy Hess Corp. and assume a 30% foothold in Guyana has been complicated by Exxon Mobil and CNOOC's claims that they have the right of first refusal for the interest.

Exxon Mobil Green-lights $12.7B Whiptail Project Offshore Guyana

2024-04-12 - Exxon Mobil’s sixth development in the Stabroek Block will add 250,000 bbl/d capacity when it starts production in 2027.