Energy policy and investment for the past 40 years have been driven by the premise that either the world is running out of crude oil and natural gas, or that it is running out of the “inexpensive” reserves and accordingly we must prepare for ever-higher energy costs.

Hundreds of billions in capital has been spent globally to find new supplies, devise ways to reduce exploration and extraction costs and develop cost-effective alternatives. The development of LNG export facilities around the world, petrochemical facilities in the Mideast and Russia’s efforts to develop the Sakhalin region and other Arctic oil and gas projects are all examples of developments predicated on high oil and natural gas prices, prices that many assumed would continually rise over the coming decades.

But there is unmistakable evidence that this paradigm is no more.

Innovations such as horizontal and directional drilling, multiwell pads, geosteering and other drill bit technologies—and of course hydraulic fracture stimulation, or hydraulic fracturing—have radically transformed the North American production base. U.S. reserves of natural gas have grown from about 250 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) in 2008 to almost 390 Tcf today, with additional proved reserves most evident in the Pennsylvania portion of the Marcellus Shale and in the Utica Shale in Ohio.

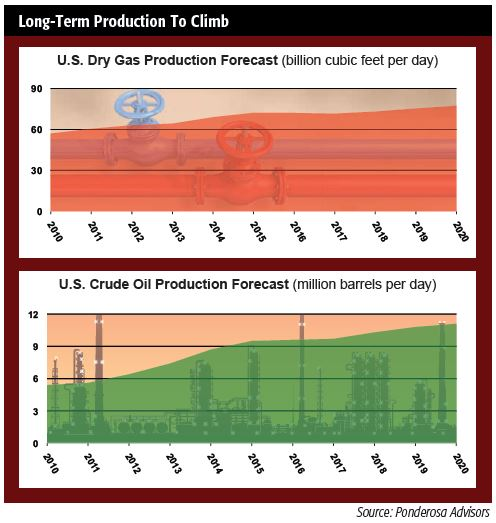

U.S. dry natural gas production is about 72 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) today, compared to 57 Bcf/d in 2010 with Northeast production—primarily the Marcellus and Utica—accounting for more than a quarter of U.S. output.

The meaning for midstream

From a midstream perspective, the rapid production growth in natural gas and crude oil over the past few years precipitated a slew of pipeline projects, in particular additional takeaway capacity for Northeast gas. Since September 2015, an additional 2.46 Bcf/d of transport capacity has come online. Ponderosa Energy also is tracking another 7.47 Bcf/d of capacity scheduled to come online in 2016, from another dozen announced projects.

In total, Ponderosa is tracking about 50 announced projects in the Northeast that have either recently come online, are under construction or have been certified by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

As the Northeast has gone from undersupplied to oversupplied in the past few years, gas from the region has traded well below the industry-standard Henry Hub price. The discount, or basis differential, occurred because of the region’s prolific gas production and its limited takeaway capacity. These new pipeline projects and their additional takeaway capacity have begun to lessen the basis differential, and though Northeast gas likely will remain discounted to Henry Hub, as more takeaway capacity comes online, it’s expected that basis spreads will tighten to the range of variable transport costs.

U.S. crude oil reserves have similarly increased as producers have learned how to extract crude molecules from tight oil deposits across the U.S. The Permian Basin in West Texas and southeast New Mexico was considered in decline as recently as 2005. Today, it is once again considered a major “frontier” area.

Innovation has so dramatically lowered the cost of exploration and extraction that some are surprised to learn that oil and natural gas can be economically produced in the best U.S. locations at well below $50 per barrel and $3 per million Btu (MMBtu), respectively.

Supply overhang

The state of the global crude oil market typifies this new era. In late 2015, the world produced about 2.4 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d) more supply than it consumed, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). That overhang is the principal cause of current low global crude prices, which have fallen more than 50% since June 2014. To effect higher prices, either supply must slow relative to demand or demand must rise relative to supply.

The main uses of crude oil are for transportation fuels and the production of petrochemicals. The relatively weak (and weakening) states of the U.S. and global economies do not suggest that a significant increase in demand is likely, much less imminent. So, higher prices require significantly lower crude production.

If demand holds constant, “significant” means the world has to produce some 2 MMbbl/d less than it does today. If demand grows slightly, subtract the incremental growth from 2 MMbbl/d to estimate how much supply must fall.

The reality is that despite crude oil prices averaging about $50 per bbl in 2015, U.S. production rose by about 800,000 bbl/d compared to 2014, jumping from an average of about 8.6 MM bbl/d to more than 9.4 MMbbl/d according to Ponderosa Energy, the energy arm of Ponderosa Advisors. Ponderosa Energy’s detailed model of production costs suggests that the U.S. can add about 1.86 MMbbl/d of incremental crude supply by the end of 2020 at an average price of $50 per bbl.

That’s correct—even at $50 per bbl, U.S. operators in what we consider Tier 1 fields can economically produce crude oil.

The new world order

U.S. production is just part of the new world order oversupply story. OPEC produced record volumes of crude oil in 2015. IEA said the cartel’s member nations produced more than 31.7 MMbbl/d late last year, as record output from Iraq of more than 4 MMbbl/d offset lower production from Saudi Arabia.

Given statements by OPEC that it expects to continue producing at least at its current rate, and by Russia and Iran that they expect to increase their production (Russia produced a post-Soviet record 10.8 MMbbl/d last year), it is difficult to see how production will slow enough to quickly reduce the supply overhang. Without significantly stronger demand, the overhang will persist and prices will remain soft, likely at least into 2018.

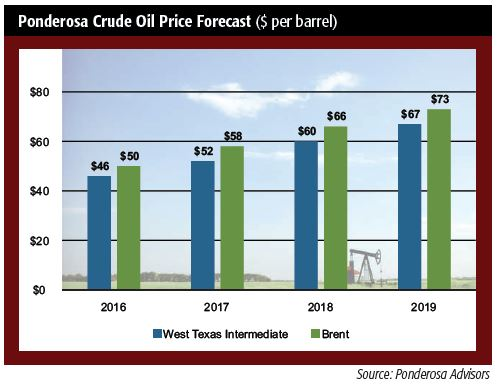

Ponderosa forecasts West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil will average $46 per bbl in 2016. Our expectation is that the supply overhang will continue at least through 2017 and that WTI prices will not reach $60 per bbl as an annual average until 2018.

Though U.S. production of crude oil has diminished some of the concerns about how world political events can impact world supply and cause market chaos, the Mideast and OPEC still holds some sway, and Russia has become a major player as well. Tensions between OPEC and Russia are often cited as being most likely to upend the current market.

A ‘war premium’

One theory is that Russian President Vladimir Putin is stirring turmoil in the Mideast in order to drive up the price of crude via a perceived “war premium.” There is no question Russia has increased its production to gain at least indirect influence over a larger share of the world’s crude supply. Russia exported more than 1 MMbbl/d of crude oil to China late last year, surpassing Saudi Arabia as Beijing’s leading supplier.

Chinese demand—or at least the expectation of greater demand—was one reason prices jumped above $60 per bbl during the first half of 2015. China, the world’s second-largest economy, is seen as having the greatest potential for increased global demand for crude, and Russia wants as much of that market as it can get, which is why Moscow and Beijing have signed energy deals worth more than $500 billion over the next 20 years, according to Igor Sechin, CEO of Russian oil major Rosneft.

Given the current state of the crude market, and more importantly the weak state of the global economy, this strategy is likely to fail and may very well backfire on the Russian leader. Assume that in the short term Putin can drive the global price to $70 per bbl. (Most estimates say that Russia needs $100 per bbl crude to generate the cash reserves needed to finance its government.) If Putin should succeed in driving prices to $70 two outcomes are likely:

1. Crude demand will fall. The well-documented elasticity of demand will drive overall consumption down, and there also is a second implication. Given the weak states of the European, Japanese and Chinese economies, those countries could be driven into recessions. It’s important to note that much of the increased demand from China is crude the country is buying at low prices to move into storage. China already has about 220 MMbbl in storage, is building another 132 MMbbl of capacity, and has planned another 149 MMbbl of storage. That’s a half-billion barrels of storage capacity for crude, but that demand will slow at higher prices. Also note that in countries such as the U.S. and Brazil, higher costs for crude mean higher costs for refined fuels, which will lower demand and offset the increased production benefits of higher prices. All things considered, it is likely that raising prices even to $70 will lower global demand.

2. The global supply of crude will increase. Consider the U.S. market. In the fall of 2014, when prices were still above $80 per bbl, there were more than 1,900 rigs active in the U.S. and crude output was growing at a month-over-month rate of 100,000 bbl/d. If prices rise to $70, Ponderosa’s model suggests that U.S. production will increase by more than 4 MMbbl/d above production levels at $50, and Canadian production will rise as well. It also is likely that non-North American production will increase as prices rise.

Taken together, these two outcomes suggest that if Putin were successful in driving up prices, the rise would be temporary.

In all likelihood a temporary rise would be followed by a subsequent and precipitous price decline. Under this scenario, it is likely that the decline will reach levels lower than would be needed to clear the market under the “base case,” and thus the Russian strategy would backfire.

That analysis suggests a powerful and relatively low-cost way to counter Russian advances, not only in the Mideast, but also in Europe. Low crude oil prices deprive Russia (and other energy-reliant bad actors) of much-needed cash to fuel their domestic economies. Continued weak economies will increase the pressure on those countries’ leaders to focus less on obstreperous behavior overseas and more on improving the plight of their citizens.

The export signal

U.S. exports of crude oil are likely a signal to these countries and the rest of the world that the era of high-priced crude is over. The U.S. (and perhaps Canada or other partners) is prepared to enforce a low-price environment. One must recognize, however, that following such a path may open Pandora’s Box: The stress on the global economy brought about by low crude prices may cause civil unrest and political chaos in many of the impacted countries, especially those that rely on energy revenues to finance their government.

Few if any analysts or producers envision crude oil prices returning to levels above $100 per bbl. OPEC and others, though, have cited $80 as a target for 2020. Ponderosa Energy expects prices near $70 per bbl at that time. Putting U.S.-produced crude oil into play on the world market would likely limit upward price movements and would increase U.S. influence over global supply.

Lower prices for crude oil and the resulting slowdown in U.S. production growth pushed out the time line for when U.S. exports would have become necessary, though it’s interesting to look at the scenario that could have occurred had U.S. output growth continued and the federal government not lifted the ban on exports. Current U.S. refining capacity is about 18 MMbbl/d. With refineries running at 92% utilization, the U.S. is refining 16.5 MMbbl/d.

The U.S. imports about 3 MMbbl/d from Canada and another 1 MMbbl/d of structural imports—crude oil headed to foreign-owned refineries. Those imports are not going away.

So the effective refining capacity for domestic crude is about 12.5 MMbbl/d. Before U.S. production reaches 12.5 MMbbl/d, exports would have been important because of quality issues, as the U.S. produces mostly light crude but many refiners want heavy crude. In fact, most imports of light crude already have been pushed out by increased domestic output, and the U.S. already has begun exporting light crude.

Producers’ problem

The problem producers face is the mismatch between increased production of light crude and refinery configurations that favor heavy crude. This means that U.S. producers increasingly have been forced to sell their light barrels to domestic refineries at a significant discount, instead of sending them to foreign markets where the light crude is a better fit.

If U.S. refiners had to take more domestic light barrels, mid-to-heavy imported barrels would need to be displaced as production grows—or at least that was the scenario until the export ban was lifted. Now, U.S. producers could send out light crude and the country can import more heavy crude. With the ban in place, and based on Ponderosa’s latest U.S. production forecast, implied imports of crude oil would have fallen by 1.7 MMbbl/d in 2020, and most of that would have been heavy crude.

Ponderosa Energy has had the opportunity to work both directly and indirectly with different groups tasked by the federal government with analyzing the implications of U.S. exports of crude oil. The Ponderosa Crude Flow Model was cited in the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s “Quadrennial Energy Review.” We maintained that the export ban would be lifted, as it was late in 2015. As production growth has slowed, the U.S. is not approaching the 12.5-MMbbl/d effective refining limit as rapidly as a year ago, so exports were not a necessity, but U.S. exports of crude oil will help domestic producers in the long term.

Had exports not been approved, and U.S. production growth resumed so that output approached the refining capacity limit, the ban on exports would have created a scenario where WTI-Brent spreads would widen dramatically. (Retail gasoline prices track with Brent crude prices, so retail gasoline prices would be higher even with lower domestic crude prices.)

That would be the worst of both worlds for the U.S. economy and gasoline consumers. Had the export ban not been lifted, that price situation would likely have encouraged legislation to lift the ban.

Recommended Reading

CERAWeek: JERA CEO Touts Importance of US LNG Supply

2024-03-22 - JERA Co. Global CEO Yukio Kani said during CERAWeek by S&P Global that it was important to have a portfolio of diversified LNG supply sources, especially from the U.S.

Excelerate Energy’s CEO Kobos Bullish on US LNG

2024-02-22 - In a world rattled by instability, his company offers a measure of energy security to natural gas users via its fleet of floating storage and regasification units.

CERAWeek: Tecpetrol CEO Touts Argentina Conventional, Unconventional Potential

2024-03-28 - Tecpetrol CEO Ricardo Markous touted Argentina’s conventional and unconventional potential saying the country’s oil production would nearly double by 2030 while LNG exports would likely evolve over three phases.

Tinker Associates CEO on Why US Won’t Lead on Oil, Gas

2024-02-13 - The U.S. will not lead crude oil and natural gas production as the shale curve flattens, Tinker Energy Associates CEO Scott Tinker told Hart Energy on the sidelines of NAPE in Houston.

ConocoPhillips CEO Ryan Lance Calls LNG Pause ‘Shortsighted’

2024-02-14 - ConocoPhillips chairman and CEO Ryan Lance called U.S. President Joe Biden’s recent decision to pause new applications for the export of American LNG “shortsighted in the short-term.”