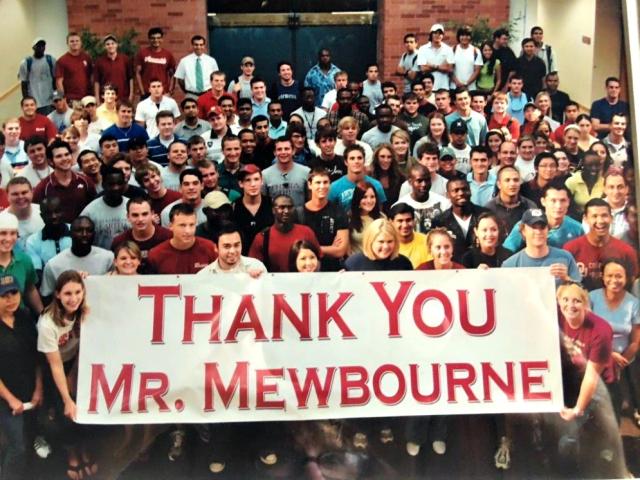

More than 6,300 students have graduated from the Mewbourne School of Petroleum and Geological Engineering. (Photo courtesy of Mewbourne Oil Co.)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the May 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

In 1919, Oklahoma had been a state for only 12 years, and Erle P. Halliburton had just established his first oilfield service company. That spring, a young man named Leon Everette English walked across the stage at the University of Oklahoma’s commencement ceremony, making history as the first person in the U.S. to earn a degree in geological engineering. Later that same year, the university expanded its curriculum to add courses in petroleum technology as well.

Later, these two disciplines were combined into one school. Since 2000, it has been known as the Mewbourne School of Petroleum and Geological Engineering (MPGE), after celebrated alumnus and independent oilman Curtis W. Mewbourne of Tyler, Texas. Housed within the Mewbourne College of Earth and Energy at the University of Oklahoma, the school is one of the oldest, ranking among the top programs in the nation. It regularly attracts students from all over the world.

Mewbourne graduated from OU in 1958 and has been a devoted booster ever since. Through years of building a successful E&P company, he has donated significant sums to the school, but more important, he’s persuaded other alums to do the same. He’s created and endowed seven chairs at the school.

Bill Banowsky was OU president in 1981 when Mewbourne first raised the issue of endowing a chair. “I walked into Bill’s office at OU in 1981 and told him I was creating the first professorship of engineering for the university. He nearly fell out of his chair. He told me, ‘Curtis, no one has ever offered me this much money unsolicited, since I became president.’”

Recall that in the early 1980s, the oil and gas industry was entering a severe depression marked by layoffs, and students did not want to enter the industry. Many people at the school were getting discouraged.

“I wanted to give them some support and hope, and let them know there was a whole great world out there,” Mewbourne said, “so that year, I also called several CEOs of large companies and asked them for $20,000 contributions for scholarships, which I said I would match. All everybody said was, ‘Just tell me how to make out the check.’ No one questioned it, because this was for the kids.”

Plans are underway now to mark the 100th anniversary of the school, including placing a new granite memorial on campus. At a gala to be held in September, distinguished alumni (many of whom are CEOs of oil and gas companies), industry executives, politicians and academics will gather to honor the research, scholarship and leadership the school has provided over a century.

More than 6,300 graduates hail from the school. Many have gone on to become leaders and influencers throughout the oil and gas industry, including serving as CEOs and other C-suite executives for Conoco and Phillips Petroleum (well before the two merged), Kerr-McGee Corp., Texaco and ExxonMobil Corp. This legacy is ongoing; graduates from May 2018 were hired by a who’s who of U.S. companies: Anadarko Petroleum Corp., Marathon Oil Co., Chevron Corp., Schlumberger Ltd. and XTO Energy Inc., among others.

“OU plays in the big leagues

in petroleum engineering.”—Curtis Mewbourne, Mewbourne Oil Co.

Recently, MPGE alumni Ashraf Al-Tahini was awarded the 2018 SPE International Award as a distinguished member, recognizing significant technical and professional contributions to the industry and contributions of exceptional service and leadership to the Society of Petroleum Engineers.

“OU plays in the big leagues in petroleum engineering,” Mewbourne said, “even though we get minor state support compared to the Texas schools. We have to continue to get the support of our graduates.”

The School Today

The school has 407 students today, including 113 graduate students.

Overseeing the programs is Mike Stice, dean of the College of Earth and Energy, who joined OU in 2015 after a career at Chesapeake Energy Corp., ConocoPhillips Co. and Access Midstream. He served on the board of visitors for about 20 years before that. He told Investor that the evolution of the industry’s technical prowess over 100 years is monumental, of course, but even just the strides made in the past decade or so have been significant enough to have turned the U.S. into a net oil and gas exporter

In 2003, Stice served on the National Petroleum Council, a group of industry experts that advises the secretary of energy. It concluded then that the oil and gas industry in the U.S. “was basically over,” he recalled.

“That was 16 years ago, and we couldn’t have been more wrong. I believed so strongly in those experts that I changed my career, went overseas to Qatar for ConocoPhillips and sought to bring LNG back, just to keep the lights on in the U.S.”

Later he joined Chesapeake, which operated in nearly every shale basin, so he could learn from the shale revolution. That knowledge is imparted to OU’s students each day through classes and affiliated research projects with oil and gas companies.

Major Changes

into account that

today’s students

differ from 10

years ago, let

alone 100 years

ago, said Mike

Stice, dean,

the Mewbourne

College of Earth

and Energy at

the University of

Oklahoma.

“One hundred years ago, the journey was about applying geology, for finding traps, seals, migration pathways from existing sources of hydrocarbons, but today, it’s more about technology and how you complete a well; how you tap into literally the source rock and unleash that precious oil and gas,” he said. “One hundred years ago, it was about finding deposits that had migrated from kitchens; now we’re getting to the source.

“How do you get what was once thought to be unmovable to actually move to the wellbore?”

Many questions remain, not least of which is why, even with proper stimulation, a seemingly impervious material can flow.

OU is a Carnegie-designated Tier 1 research university, meaning it belongs to an elite group of 120 educational institutions in the U.S. that have the highest level of funded research activity and highest number of people engaged in that research. The Mewbourne School plays a big role, often collaborating with the energy industry in various consortia initiated either by industry partners or by the university itself.

In order to study images of rock at the nano level, the school has lab equipment unrivaled even by some of the majors. “We can take a rock in our lab and put it under the same pressure as if it were 10,000 feet under the ground, look at cores at the nano level and see what it will take to stimulate it,” Stice said.

Though the rocks haven’t changed in a hundred years—indeed not in a million—the way someone can look at them and make them produce has changed dramatically. So, too, have the students themselves changed.

“The student of today is quite different than the student of 10 years ago, much less the student of 100 years ago,” Stice noted, citing the evolution of social media and technology, and the ability to search for information immediately via a cell phone.

“I read a study that said the average young person now has an attention span of three minutes. If the average student has an attention span of three minutes, you’ve got to keep information fresh and make sure you haven’t lost your audience. We used to have lectures when I was in school, but today there’s a lot more interactivity and a lot more of a Q&A format, because the main information can be conveyed outside the classroom and students already come in to class well-prepared.”

Lectures where the student listens passively are out. Today there’s more lab time, more hands-on experiential learning and more time spent building judgment that leads to good decision-making. Internships play a role, but as well, the school has developed a simulated oil and gas office environment where students work on real-world projects brought to them by oil and gas companies.

“We are so lucky to be right in the middle of the oil industry. If we need to see a completions job, we literally can get in a car and go to see a well in 30 minutes,” Stice said.

The proof is in the value delivered. Last December, some 21 graduates submitted their starting salary numbers for petroleum engineering and the average was $76,000. One young woman, who had stayed a fifth year to get her extended MBA, started at $112,000, Stice said.

Donor support, committed faculty, generous alumni and industry collaboration have contributed to making the last 100 years fruitful, and that will continue. Recently, Mewbourne challenged alumni that if they’d give a gift of any size for faculty support, he would match that dollar for dollar, with the goal of supporting existing faculty and bringing in top-notch additional people as well. The alumni responded enthusiastically, pledging $4.1 million, and he matched that amount.

“Our vision is that we’re committed to our great reputation as one of the best petroleum engineering schools in the world. We’re going to do everything to see that that reputation continues,” Mewbourne said.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR:

The Man Behind The Name

Curtis Mewbourne is a highly successful entrepreneur who at age 83 remains actively engaged in the business he’s built, Mewbourne Oil Co., and in promoting his beloved University of Oklahoma.

The private company is a family-owned business that he founded in 1965 in Dallas, with his last paycheck; he started in a one-room rented office. Today it is one of the largest, if not the largest, privately held oil producers in the U.S., and is based in Tyler. He says proudly that the company has always operated, and has always stayed within cash flow: “We operate everything we do.”

The private company is a family-owned business that he founded in 1965 in Dallas, with his last paycheck; he started in a one-room rented office. Today it is one of the largest, if not the largest, privately held oil producers in the U.S., and is based in Tyler. He says proudly that the company has always operated, and has always stayed within cash flow: “We operate everything we do.”

It’s all backed by the loyal efforts of the roughly 500 employees in six district offices, including the new 24,000-square-foot building in Hobbs, N.M., that was dedicated in 2017 with the New Mexico governor in attendance.

Mewbourne’s oil production has grown at a compound annual rate of 30% over the last 10 years, and it’s all focused in the Anadarko and Delaware basins. The company had 11 rigs running at press time—down from 19 before the fourth-quarter 2014 oil crash.

“We are long term; we’ve built this to last for generations,” said Mewbourne. “The three things that will write the obit for any independent oil company are debt, estate taxes and succession planning, and I’ve taken care of all three.”

Why has Mewbourne Oil Co., which frequently joint ventures with majors and many large independents, as the operator, done so well? His answer, in a word: people.

“People are more important than assets. People are everything,” Mewbourne said. “We kept hiring every single year right through the downturns, from right out of the colleges [OU, Texas Tech and several other schools], and very few have ever left.

“We learned something from watching the old Humble Oil [now ExxonMobil] and other majors; they knew how to build a company. You need boots on the ground.”

Those who know Mewbourne agree he is a force of nature.

“He is a joyful person, almost overly energetic and easily excited by projects. You almost have to get out of his way—that kind of enthusiasm is inspiring, and it’s kind of hard not to get excited too. He does drive things,” said Mike Stice, dean of OU’s Mewbourne College of Earth and Energy.

“I’ve been blessed to have relationships with a number of people from what I’d call ‘Curtis’ generation,’ and he clearly is a standout in that group. Mewbourne may not be a household name, but he is a quiet achiever. The people in his company have an amazing work ethic and tremendous entrepreneurism, and most of that came from his leadership,” Stice said.

Mewbourne’s biggest strength is his ability to recognize talent early and put that talent to work where it can test that strength, Stice said. “He’s a real talent manager. I’ve seen what he’s done to identify talent at a young age, and then give them plenty of hands-on experience so that when they reach middle management, they will make the best decisions.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Leslie Haines can be reached at lhaines@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

Clean Energy Begins Operations at South Dakota RNG Facility

2024-04-23 - Clean Energy Fuels’ $26 million South Dakota RNG facility will supply fuel to commercial users such as UPS and Amazon.

Romito: Net Zero’s Costly Consequences, and Industry’s ‘Silver Bullet’

2024-04-22 - Decarbonization is generally considered a reasonable goal when presented within the context of a trend, as opposed to a regulatory absolute.

Energy Transition in Motion (Week of April 19, 2024)

2024-04-19 - Here is a look at some of this week’s renewable energy news, including the latest on global solar sector funding and M&A.

Eversource to Sell Sunrise Wind Stake to Ørsted

2024-04-19 - Eversource Energy said it will provide service to Ørsted and remain contracted to lead the onshore construction of Sunrise following the closing of the transaction.

Exclusive: Building Battery Value Chain is "Vital" to Energy Transition

2024-04-18 - Srini Godavarthy, the CEO of Li-Metal, breaks down the importance of scaling up battery production in North America and the traditional process of producing lithium anodes, in this Hart Energy Exclusive interview.