Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s recent statement that it intends to acquire BG Group Plc for $70 billion in cash and shares was one of the biggest announcements in the industry in decades. It also has industry players scrambling to determine what it means for the future. Shell was willing to pay BG shareholders a 50% premium on what their holdings were worth just prior to the bid. Naturally there are some big questions to be answered: Why was Shell willing to pay such a premium? What does it portend about future M&A activity and the energy business as a whole? Are we facing a new round of super mergers like the ones that created Exxon Mobil, BP Amoco and TotalFinaElf? Exxon Mobil is in a strong cash position, holding about $300 billion in U.S. treasury notes alone.

Global strategy

The proposed acquisition appears to be a unique fit that returns Shell to the global natural gas strategy it embarked on in the 1990s, one in which LNG markets will enable the monetization of previously stranded gas resources worldwide. While BG is relatively small compared to Shell, it has a huge portfolio of assets and projects that will complement Shell’s existing position in Atlantic LNG, Brazil, Australia and Africa.

The acquisition will result in a company that produces more than half the LNG produced by the entire country of Qatar. It would make Shell the world’s third-biggest natural gas producer, behind Russia’s Gazprom and the National Iranian Oil Co.

Shell missed out on the merger mania of the late 1990s and was criticized by many shareholders and market analysts for moving too slowly and missing out on an opportunity to expand. Today, however, Shell is the first mover, making a big strategic move in a new era where low commodity prices and the availability of cash are creating many potential mergers and acquisitions (M&A). But will there be similar M&A? The combination of some companies sitting on cash plus distressed assets that may complement portfolios makes this possibility more likely.

Conventional, unconventional opportunities

It is clear that opportunities exist and that companies with deep pockets, such as Exxon Mobil and Chevron, are poised to jump in. In general, these companies are having a harder time growing organically. But it also is important to realize what kinds of opportunities they may seek.

Many independents that have been active in the relatively expensive unconventional resource plays are struggling and appear to be especially ripe for the picking. But supermajors have struggled in the shale plays. And it doesn’t seem likely that in this price environment they will be willing to double down.

Instead, it seems likely that their efforts will focus on companies with more conventional assets, both onshore and offshore, with global portfolios. Like Shell, these companies are looking at longer term horizons and opportunities to replace and grow reserves over decades.

As for the shale players, it seems more likely that marriages of convenience will dominate. Combinations of companies with complementary portfolios appear likely as companies look to reduce costs and increase efficiencies. M&A activity is one of the easiest ways to get there. It is not hard to imagine that in the near future a class of super-independent shale operators will exist to capitalize on the application of proven techniques in the “manufacturing” phase of shale production.

In the service sector there will likely be liquidation and consolidation on a very broad scale as service companies become insolvent and assets are acquired by stronger competitors or creditors. This is already occurring on a growing scale. This landscape is likely to look much different by the time commodity prices recover.

About that recovery

The trillion-dollar question is, “When will the market recover?” Currently, things don’t appear to be moving in that direction. Saudi Arabia has boosted crude production to its highest rate on record, according to its oil minister, Ali al-Naimi. A sudden wave of demand from refiners and increased production at home is resulting in more Saudi crude in the market.

While demand is up in Asia, Saudis have walked up the price on exported crude that was initially discounted. This may be an example of the overall strategy of Saudi Arabia―to keep prices low until buyers start to buy, thus gaining market share. Once it has market share, the price will go back up. The kingdom produced a record 10.3 MMbbl/d of crude in March. The previous peak was 10.2 MMbbl/d in August 2013. This increase in output demonstrates that Saudi Arabia is sticking to its vow not to give away markets to U.S. shale producers or to Russia. Russia, like any good petrostate in a time of depressed oil prices, is flooding the market along with Venezuela, Libya, Iran, Algeria and many others. Its only solution is to pump its way back into the black.

Overall, OPEC continues to be unwilling (and outside of Saudi Arabia, unable) to cut production to remedy low oil prices.

For prices to recover, production will likely need to be cut somewhere, and that will begin with a slowdown in exploration (Figure 1). There is evidence that this cycle of events is already occurring. Baker Hughes stated there were 2,557 rigs in service worldwide in March 2015, down 14% from the previous month and 29% less than March 2014.

FIGURE 1. Exploration costs are expected to change in 2015. Liquidation and consolidation are already occurring on an increasing basis. (Source: Wood Mackenzie Future of Exploration Survey 2015)

Offshore, the rig count for March was 316, down eight from February and down 18 year-on-year. U.S. rig counts are down 17% from March, and North Dakota’s rig count fell 50% year-to-year.

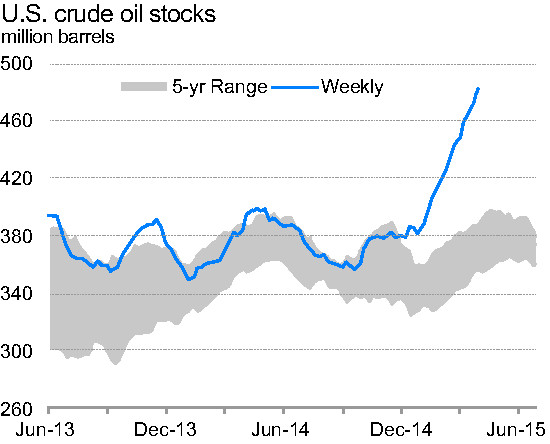

On average, industry budgets are being slashed by 30%, which is a trend that will eventually impact supply and price, but not for many months. Crude oil stocks also are soaring, as seen in Figure 2. This puts additional downward pressure on oil prices.

Interplay with monetary policy

Historically, a stronger dollar has coincided with a decrease in the price of oil and vice versa. Today’s strong dollar brings no exception. Currently, the Federal Reserve System (Fed) views the strong dollar as a hedge against inflation. This hedge will allow the Fed to extend its timeline for increasing interest rates, providing more capital to fund M&A activity.

FIGURE 2. U.S. crude oil stocks are soaring, which adds pressure to lower prices. (Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

Finally, there is geopolitics. Continued turmoil in the Middle East and Africa―ISIS, Yemen, Syria and Boko Haram―are all factors that could and normally would drive oil prices higher. But fundamentals, namely supply continuing to outpace demand, are countering any impact from world events.

With a commodity price recovery likely many months away, the upstream sector has some challenging months ahead. No doubt there will be a whole host of changes including bankruptcies, layoffs, divestitures and M&A. Other companies may follow Shell’s lead, taking advantage of this opportunity to position themselves for a long-term success.

Recommended Reading

Athabasca Oil, Cenovus Energy Close Deal Creating Duvernay Pureplay

2024-02-08 - Athabasca Oil and Cenovus Energy plan to ramp up production from about 2,000 boe/d to 6,000 boe/d by 2025.

Novo II Reloads, Aims for Delaware Deals After $1.5B Exit Last Year

2024-04-24 - After Novo I sold its Delaware Basin position for $1.5 billion last year, Novo Oil & Gas II is reloading with EnCap backing and aiming for more Delaware deals.

CEO Darren Woods: What’s Driving Permian M&A for Exxon, Other E&Ps

2024-03-18 - Since acquiring XTO for $36 billion in 2010, Exxon Mobil has gotten better at drilling unconventional shale plays. But it needed Pioneer’s high-quality acreage to keep running in the Permian Basin, CEO Darren Woods said at CERAWeek by S&P Global.

Uinta Basin's XCL Seeks FTC OK to Buy Altamont Energy

2024-03-07 - XCL Resources is seeking approval from the Federal Trade Commission to acquire fellow Utah producer Altamont Energy LLC.

Analysts: Why Are Investors Snapping Up Gulfport Energy Stock?

2024-02-29 - Shares for Oklahoma City-based Gulfport Energy massively outperformed market peers over the past year—and analysts think the natural gas-weighted name has even more upside.