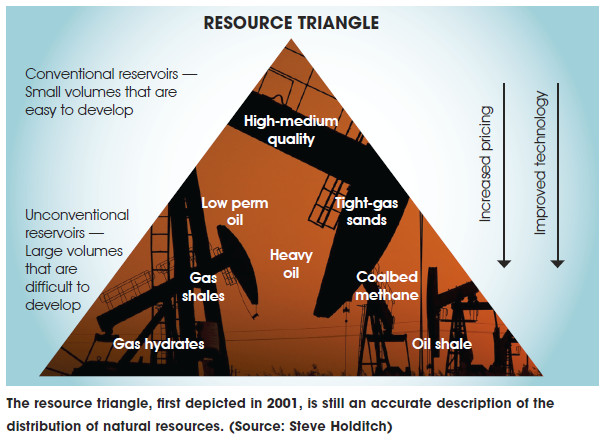

“Tap unconventional reservoirs” was the title of an article that appeared in the September 2001 edition of E&P. Cited as an E&P Executive Interview, the interviewer talked to Steve Holditch, then a Schlumberger fellow, professor of engineering at Texas A&M and incoming president of the Society of Petroleum Engineers.

In 2001 few people were considering shale oil as a viable resource, so Holditch referred to “unconventional gas reservoirs” or “UGRs.” Even then he was able to discuss the problems that operators would soon be plagued with while attempting to produce these reservoirs.

“The problems associated with UGRs are varied and dependent on geologic and other factors,” he said. “In tight gas reservoirs and gas shales, the biggest problems are low permeability and reservoir compartmentalization. In most cases, finding the gas is the easy part. The difficult part is finding the most permeable portion of the reservoir, called the ‘sweet spot.’”

The industry has heard quite a bit about these sweet spots since, and finding them is still one of the most challenging aspects of developing shale reservoirs. We caught up with Holditch recently and asked him to discuss where we’ve come since 2001 and where we’re likely to go next.

E&P: Since your last interview with us, what has been the most meaningful change in how the industry has developed unconventional reservoirs during the past 15 years?

Holditch: Fifteen years ago the industry was drilling vertical wells and pumping fracture treatments in one or more reservoir layers, mainly looking for natural gas. In 2016 the industry routinely drills horizontal wells 1 mile or 2 miles [0.6 km to 1.2 km] long, pumping 20 to 30 (or more) stage fracture treatments and mainly looking for oil. What the industry is doing in 2016 is totally different than in 2001.

E&P: How has our level of understanding and knowledge about unconventional reservoirs evolved?

Holditch: The level of understanding the industry has in 2016 compared to 2001 is remarkably better in almost every aspect of oil and gas development. In 2001 many companies were looking at unconventional gas and drilling vertical wells looking for ‘sweet spots,’ sometimes using 3-D seismic to locate wells. However, most wells were drilled on a pattern to hold acreage, and the sweet spots were found by just drilling more wells. It also was believed that we could mainly produce natural gas from shale reservoirs because crude oil was too viscous to flow from the shale matrix into the fracture and then into the wellbore.

In 2016 most companies developing shale reservoirs are actively targeting oil in the shale formations and creating their own flow paths from the matrix into the hydraulic fractures. They do this by creating a network of fractures and opening natural fractures by pumping 20 to 30 or more large-volume fracture treatments down a long horizontal wellbore.

Companies also are using 3-D seismic and 3-D earth models to better understand the layers in the formations that are the most productive and the layers that control fracture height growth. Companies use the 3-D information to place the horizontal wells into targeted layers. The companies also are using microseismic information to better understand where and how induced fractures grow and interact with the layers.

E&P: Was the level of difficulty in recovering resources from unconventional reservoirs greater than predicted/estimated? What has happened between 2001 and now that has surprised you or that you didn’t expect?

Holditch: It was clear in 2001 that a lot of natural gas was trapped in tight gas sands, coalbed methane and shale reservoirs. Research into the distribution of natural resources clearly shows that we have more than 100 years of natural gas supply in unconventional reservoirs if the gas price is high enough and the infrastructure, such as pipelines and markets, exists near the gas deposit. As the industry transitioned from drilling vertical wells in gas reservoirs like the Barnett Shale, Marcellus Shale and Haynesville Shale, and as the horizontal well lengths increased, the increase in gas flow rates and ultimate recovery was surprising. I do not believe anyone truly predicted what would happen with gas well productivity during 2001, but as the industry kept drilling and kept innovating, the results just seemed to keep getting better.

Even with the improvements in natural gas recovery in the mid-2000s, I do not think many people thought we could produce oil from these nano-Darcy reservoirs. To me the most surprising result in the last 15 years is how much oil the industry is producing from the Bakken, the Eagle Ford and in the Permian Basin from shale formations. Many of these formations have long been considered the source rocks. In the 1970s and 1980s everyone knew the source rock for the Austin Chalk Formation was the Eagle Ford. No one that I knew could have predicted the Eagle Ford source rock would turn out to be such a productive reservoir.

E&P: Did you anticipate just how crazy things were going to get in unconventionals?

Holditch: No, I did not predict how ‘crazy’ things would get in the development of unconventional reservoirs. However, the U.S. is the hotbed of entrepreneurship in the world. Our culture allows us to develop technology, develop business plans and take risks. So looking back, it is not surprising that hundreds of companies were formed or focused their business on developing shale reservoirs. My guess is some of the companies wish they had not grown so fast and/or used less debt for growing their business.

E&P: What was the greatest/most difficult obstacle to overcome in recovering resources from unconventional reservoirs?

Holditch: I am not sure there was a single obstacle to overcome but a series of obstacles that are interrelated. The key to success has been the ability to drill long horizontal wells and then to fracture-treat the wellbore with 20 or more stages. To drill the long horizontal wells, we had to have improvements in rigs, drillbits, drilling mud, MWD, steel metallurgy and geosteering—to name a few of the technologies. To fracture-treat these long horizontal wells, we had to build hundreds of new fleets of fracture treatment pumping equipment, develop techniques to isolate stages in the borehole, learn the best fluids to pump and develop new sand mines to keep up with demand.

The biggest obstacle might have been the logistics of organizing all the equipment and people required to support the hectic pace of the past 10 years.

E&P: What ‘low-hanging fruit’ remains for technologists to pick when it comes to unconventional reservoirs?

Holditch: The obvious target for ‘low-hanging fruit’ is refracturing, but it is not really that easy to do. Sure, we can pump refracture treatments in existing wells and use particulates to try to divert the stages from one set of perforations to another. However, it is doubtful that a large refracturing campaign would be overwhelmingly profitable. A few wells may produce large increases in production, but most will not. The service companies need to develop new technology to isolate portions of the wellbore to be refractured so the treatments can be targeted to specific locations. Once such technology is developed, then refracturing could be more profitable. The key will be developing a ‘tool’ to isolate part of the wellbore and have it designed so it does not become stuck in the hole because of the proppant.

E&P: What are the obstacles or ‘next-level hanging fruit’ that the industry will encounter (e.g., EOR, artificial lift, monitoring, etc.)?

Holditch: I am not hopeful any EOR method will emerge anytime soon. It is difficult to make money with EOR in permeable reservoirs. The only EOR method that has some opportunity would be using a chemical to dislodge oil in small pores in a ‘huff-and-puff’ operation. Most experts believe we are only recovering 5% to 10% of the oil in place with our current development strategies. As such, there could be substantial volumes of oil still trapped in the reservoir near the horizontal wells that could be the target for any EOR method.

I think a more realistic view might be ‘targeted infill drilling’ on the basis of better monitoring. The industry needs to improve technology such as 3-D seismic, microseismic, tracer technology during and after fracture treatments, use of fiber optics to measure pressure and temperature along the wellbore both during and after the fracture treatment, and better models to interpret all the data obtained during monitoring. With better analyses, the industry will be able to target specific areas for infill drilling both by layer and areal extent.

If we learn more about where (which layers) the hydraulic fractures grow and more about the length and conductivity of these hydraulic fractures, we will most likely find that all of the layers in these formations that are hundreds or thousands of feet thick are not being drained efficiently. Once we can determine what part of the layered reservoir is being drained by existing wells, we can then develop an infill drilling plan to tap into the rest of the reservoir that is not being drained.

E&P: Will this unconventional drive eventually spread globally? Despite much talk of it in recent years, the activity internationally has been disappointingly sparse.

Holditch: There is no doubt in my mind that unconventional reservoirs containing enormous volumes of oil and gas exist in every oil and gas basin in the world. When a basin has produced a lot of oil and gas, it must have source rocks to have generated the oil and gas now trapped in the conventional rocks. In the U.S. we are essentially producing oil and gas from what we have always considered source rocks. So every oil and gas basin in the world has source rocks that can be produced in the future. Obviously, the key will be demand, price and infrastructure. The largest obstacle so far has been infrastructure. One has to have the markets, the legal structure, the pipelines/transportation, the rigs, the fracturing equipment and the people who know what they are doing for the successful development of an unconventional reservoir, even after the productivity of the reservoir has been established.

E&P: The 2001 article highlighted your thoughts 15 years ago, which were remarkably accurate in light of what happened in the following years. Where do you think the shale industry will be in another 15 years? Can you paint a picture for us?

Holditch: As long as the world population continues to increase and the people on Earth want a higher standard of living, we will need more energy. Western civilization is becoming more energy-efficient and is using more renewable energy. However, in most of the world there is a lack of energy for improving the standard of living. So I am assuming that the predictions that the demand for energy—and specifically oil and gas—will continue to increase for 40 years or more is a valid view of the future.

Given the assumption of an increase in global demand, I believe the oil and gas industry will continue to find and develop the supply. It is clear that the oil we will need will not come from new discoveries in conventional reservoirs. The oil the world will need will come from unconventional reservoir development such as shale and even the heavy oil from Canada and Venezuela. However, I think the development of oil and gas from shale formations is just beginning, both in North America and elsewhere in the world. Never underestimate the entrepreneurial nature of those in the oil and gas business.

For more information, contact Rhonda Duey at rduey@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

Scathing Court Ruling Hits Energy Transfer’s Louisiana Legal Disputes

2024-04-17 - A recent Energy Transfer filing with FERC may signal a change in strategy, an analyst says.

Balticconnector Gas Pipeline Will be in Commercial Use Again April 22, Gasgrid Says

2024-04-17 - The Balticconnector subsea gas link between Estonia and Finland was damaged in October along with three telecoms cables.

Targa Resources Ups Quarterly Dividend by 50% YoY

2024-04-12 - Targa Resource’s board of directors increased the first-quarter 2024 dividend by 50% compared to the same quarter a year ago.

Canada’s First FLNG Project Gets Underway

2024-04-12 - Black & Veatch and Samsung Heavy Industries have been given notice to proceed with a floating LNG facility near Kitimat, British Columbia, Canada.

Biden Administration Argues Against Enbridge Pipeline Shutdown Order

2024-04-11 - The U.S. argues that shutting down the pipeline could interrupt service and violate a 1977 treaty between the U.S. and Canada to keep oil flowing.