Raman spectroscopy is not a new technology—it was invented in 1928 and won a Nobel Prize in 1930. Raman spectrometers have been a common sight in universities and laboratories for years, large, hulking machines that take up entire rooms.

Not exactly the kind of thing you’d try to put into a wellbore.

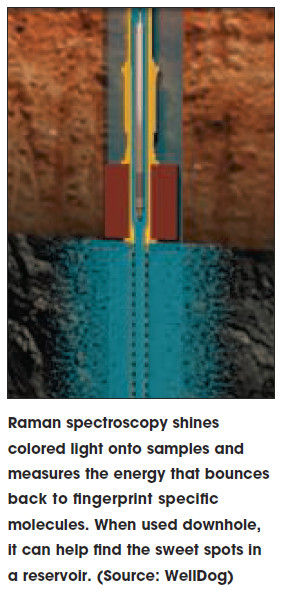

But WellDog is doing exactly that. After using Raman technology in coal mines and coalbed methane (CBM) developments for years, the company decided to apply the technology in the shale plays in the U.S. Already it had miniaturized the Raman concept into a logging tool for CBM. It has taken that farther and now offers a tool with a 2.6-in. outer diameter for shales.

“Raman spectroscopy works by shining light of one color on a sample, typically using a laser beam, and then watching as the color of the light changes when it bounces off the sample,” said James Walker, WellDog’s COO. “The amount of color change indicates the energies at which the sample is excited, which is highly characteristic of each type of molecule, and provides a fingerprint indicating the presence of the molecule. More photons at those colors indicate more of the molecule in the sample.”

He added that unlike other types of spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy is not overly sensitive to water.

As shale operators face “Shale 2.0”—the use of Big Data analytics to harvest the vast amounts of information being captured in shale plays—a better reservoir characterization tool fits the bill nicely. The company’s experience in coals has enabled it to work in high volumes, which is important in unconventional fields.

“As the volumes get bigger, our processes are fine-tuned,” Walker said, adding that the complexity of shale reservoirs is not an inconsequential challenge.

The benefits of a downhole measurement vs. a core measurement are obvious. “The customer wants information as quickly as possible,” he said. “It’s instant information; it’s a classic logging tool. The customer gets repeatable measurements and is not destroying its sample to get one answer from the lab three months later.”

The tool is now ready for commercialization for shales after a successful beta test earlier this year. A commercial launch was expected in late February. “That’s the dream,” Walker said. “If you could log the well and identify the sweet spots with a direct measurement, that would be very valuable to the operators.”

The company continues to work with the industry to find additional applications for the technology. It could potentially be used to measure fluids coming back from the wellbore as well as looking at cuttings to determine things like thermal maturity and total organic carbon. This in turn could help determine the relative ductility or brittleness of the rock. It already is being tested for use in EOR operations to determine how much CO2 is coming into a monitor well.

“This has taken years of work from a Raman spectroscopy standpoint,” Walker said. “We’re talking to the industry on how we can best apply it.

“We’re going to be here for another 50 years with shale, and this is the start of using a new suite of sensors,” he emphasized.

Recommended Reading

Santos’ Pikka Phase 1 in Alaska to Deliver First Oil by 2026

2024-04-18 - Australia's Santos expects first oil to flow from the 80,000 bbl/d Pikka Phase 1 project in Alaska by 2026, diversifying Santos' portfolio and reducing geographic concentration risk.

Iraq to Seek Bids for Oil, Gas Contracts April 27

2024-04-18 - Iraq will auction 30 new oil and gas projects in two licensing rounds distributed across the country.

Vår Energi Hits Oil with Ringhorne North

2024-04-17 - Vår Energi’s North Sea discovery de-risks drilling prospects in the area and could be tied back to Balder area infrastructure.

Tethys Oil Releases March Production Results

2024-04-17 - Tethys Oil said the official selling price of its Oman Export Blend oil was $78.75/bbl.

Exxon Mobil Guyana Awards Two Contracts for its Whiptail Project

2024-04-16 - Exxon Mobil Guyana awarded Strohm and TechnipFMC with contracts for its Whiptail Project located offshore in Guyana’s Stabroek Block.