Presented by:

This article appears in the E&P newsletter. Subscribe to the E&P newsletter here.

Brownfield offshore energy developments have an image problem. The term itself doesn’t help—greenfield sounds much nicer and far cleaner. Perhaps we can say "legacy assets" instead, but legacy is a pretty worn euphemism for old at this point.

So I won’t try to burnish the language, I’ll just make my case plainly: offshore brownfield projects will be some of the most important energy engineering projects of the decade.

The world is awash with assets reaching their stated end of life, from the North Sea to the Gulf of Mexico (GoM), the Middle East and southeast Asia. Plus, we probably haven’t reached the peak; the steadily climbing oil price of the early 2000s will have prompted a wave of projects, which will turn 25 years old over the next 10 years.

Some of these will need to be retired and decommissioned. Yet for many others, there is life in them, but for want of some intelligent engineering.

Sustained demand

According to the IEA’s 2021 World Energy Outlook, under the stated policies scenario, global oil demand is set to grow from 28 Bbbl to 32 Bbbl through to 2050. Even under the net-zero scenario, in which demand decreases, 7 Bbbl of demand remain.

These figures show that oil demand is not about to disappear anytime soon, and may in fact increase; given that fact, the question then becomes the best way to meet that demand. There are parts of the world, such as West Africa, that are investing heavily in new greenfield projects, but brownfield assets will have a part to play too, especially in more mature fields such as the North Sea and GoM.

The price is right

At the time of writing, the oil price has passed $100/bbl once again, but under the exceptional and tragic circumstances of the war in Ukraine and its geopolitical fallout. This follows more exceptional circumstances in the global markets as the wheels of the global economy had begun to turn again following the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, we must hope these tragedies pass swiftly, and when they do, oil and gas prices may again subside. Before the pandemic, our industry talked in terms of "lower for longer," and the general consensus was that the energy transition would exert downward pressure on demand and prices over time. Investment activity had evolved to be less dominated by mega projects and more concerned with asset-life extension and less permanent installations such as FPSOs.

Given that greenfield projects may have multi-decade life cycles, investment decisions must surely factor in a lower price than today’s high. This favors brownfield projects, which require lower capex and a shorter commitment.

The energy transition

Even putting price aside, there are compelling environmental reasons to look to brownfield developments to state the world’s oil and gas demand.

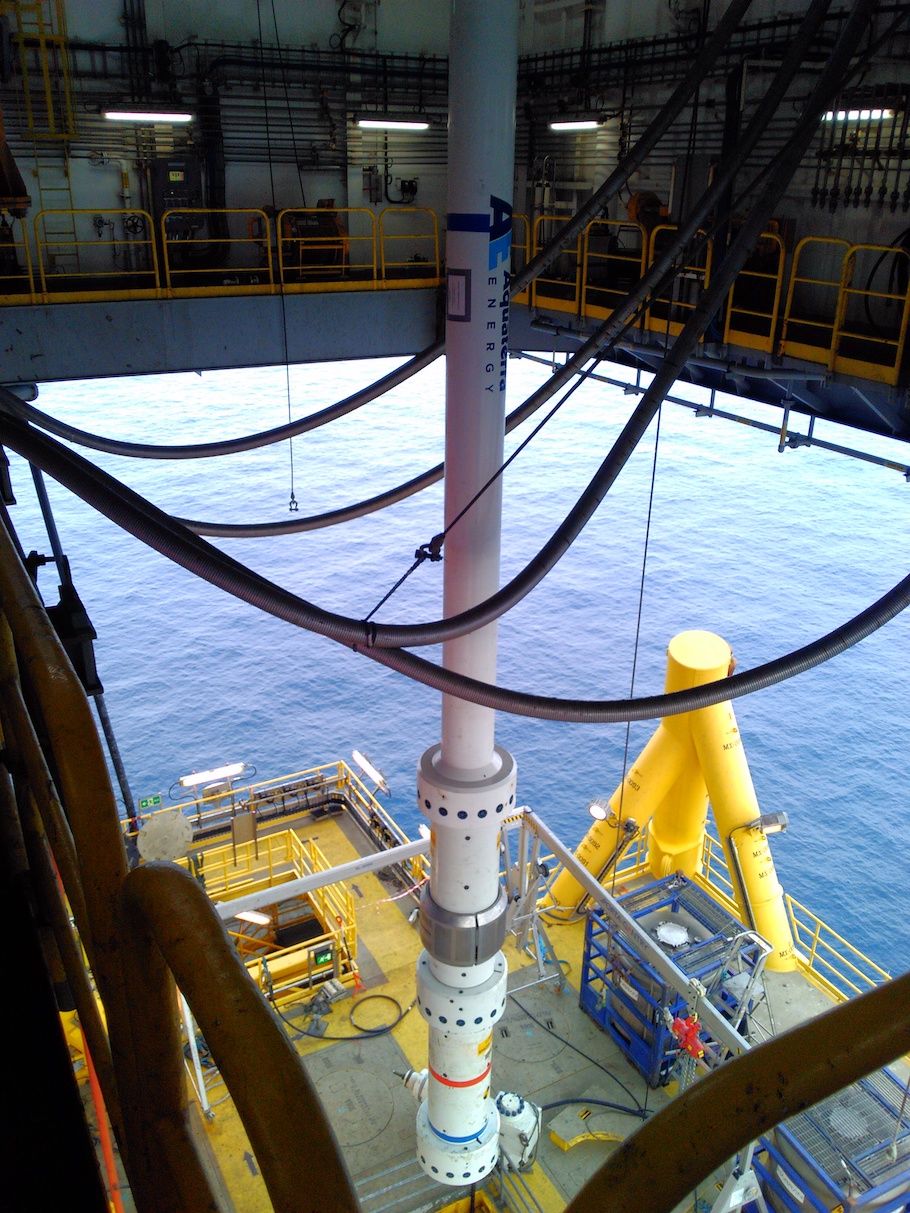

(Source: Aquaterra Energy)

First, consider materials. The volumes of steel, concrete and other carbon-intensive materials that are involved in offshore infrastructure are phenomenal, especially in deeper waters. For example, every ton of steel produced in 2018 emitted on average 1.85 tons of CO2, equating to about 8% of global CO2 emissions.

Brownfield engineering projects do often require the use of new material. A platform may have been designed with a certain thickness of steel and need to be reinforced to take the weight of a new piece of equipment, for example. However, even for the most extensive of brownfield (re)developments, the material requirements are likely to be orders of magnitude less than for greenfield alternatives, especially when the emissions for transporting those materials are factored in.

Brownfield developments can also feed into an asset owners’ energy transition strategies in more conspicuous ways. For instance, for typically unmanned platforms with low-electricity loads, it is now possible to convert them to run on renewable energy.

In the future, brownfield projects may even be at the forefront of the energy transition. Much has been made of the potential for CCS projects, using depleted reserves to store sequestered CO2, upgrading existing infrastructure already in situ to do so. We have even begun work on a concept combining oil and gas infrastructure with co-located wind resources to produce green hydrogen.

Aging assets meet intelligent engineering

However, brownfield developments are not always straightforward, for a variety of reasons.

First, there is often a documentation gap. Technical drawings and specifications can be lost over the years, updates and retrofit engineering works are not always properly captured, and documentation has a habit of going missing when assets change hands, which can happen many times over the course of an asset’s life cycle.

Once documentation is compiled and asset health is established, then the real engineering work starts. Bearing in mind that any deviation from an asset’s original intended purpose can introduce risk, its vital that this is done with precision. Say an operator wants to drill a new well and tieback to an existing platform—does it have capacity for the riser? Space top-side for additional processing equipment? Any miscalculations here can have expensive consequences.

There’s no escaping the fact that brownfield development requires real, rigorous, investigative, problem-solving engineering work. It’s a different challenge to greenfield, and one that many of the engineers I have worked with relish.

After all, the only real certainty in the industry is change. The ability to adapt and upgrade offshore infrastructure to meet the industry's needs as they evolve is arguably one of the most important tools for the sector, and that is underpinned by intelligent offshore engineering.

About the author: Stewart Maxwell is technical director with Aquaterra Energy.

Recommended Reading

Laredo Oil Settles Lawsuit with A&S Minerals, Erehwon

2024-03-12 - Laredo Oil said a confidential settlement agreement resolves a title dispute with Erehwon Oil & Gas LLC and A&S Minerals Development Co. LLC regarding mineral rights in Valley County, Montana.

Watson: Implications of LNG Pause

2024-03-07 - Critical questions remain for LNG on the heels of the Biden administration's pause on LNG export permits to non-Free Trade Agreement countries.

Yellen Expects Further Sanctions on Iran, Oil Exports Possible Target

2024-04-16 - U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen intends to hit Iran with new sanctions in coming days due to its unprecedented attack on Israel.

Kinder Morgan Exec: Building Pipelines ‘Challenging, but Manageable’

2024-04-05 - Allen Fore, vice president of public affairs for Kinder Morgan, said building anything, from a new road to an ice cream shop, can be tough but dealing with stakeholders up front can move projects along.

The Jones Act: An Old Law on a Voyage to Nowhere

2024-04-12 - Keeping up with the Jones Act is a burden for the energy industry, but efforts to repeal the 104-year-old law may be dead in the water.