Despite Quebec's ban on new oil and gas exploration and development last year, Canadian production is poised for continued growth in the coming years. (Source: Shutterstock)

While Quebec was the world’s first to ban new oil and gas exploration and development last year—although it had no production to begin with—Canada’s production, particularly in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), is poised for continued growth in the coming years. However, old and new roadblocks could pose challenges for operators in the country.

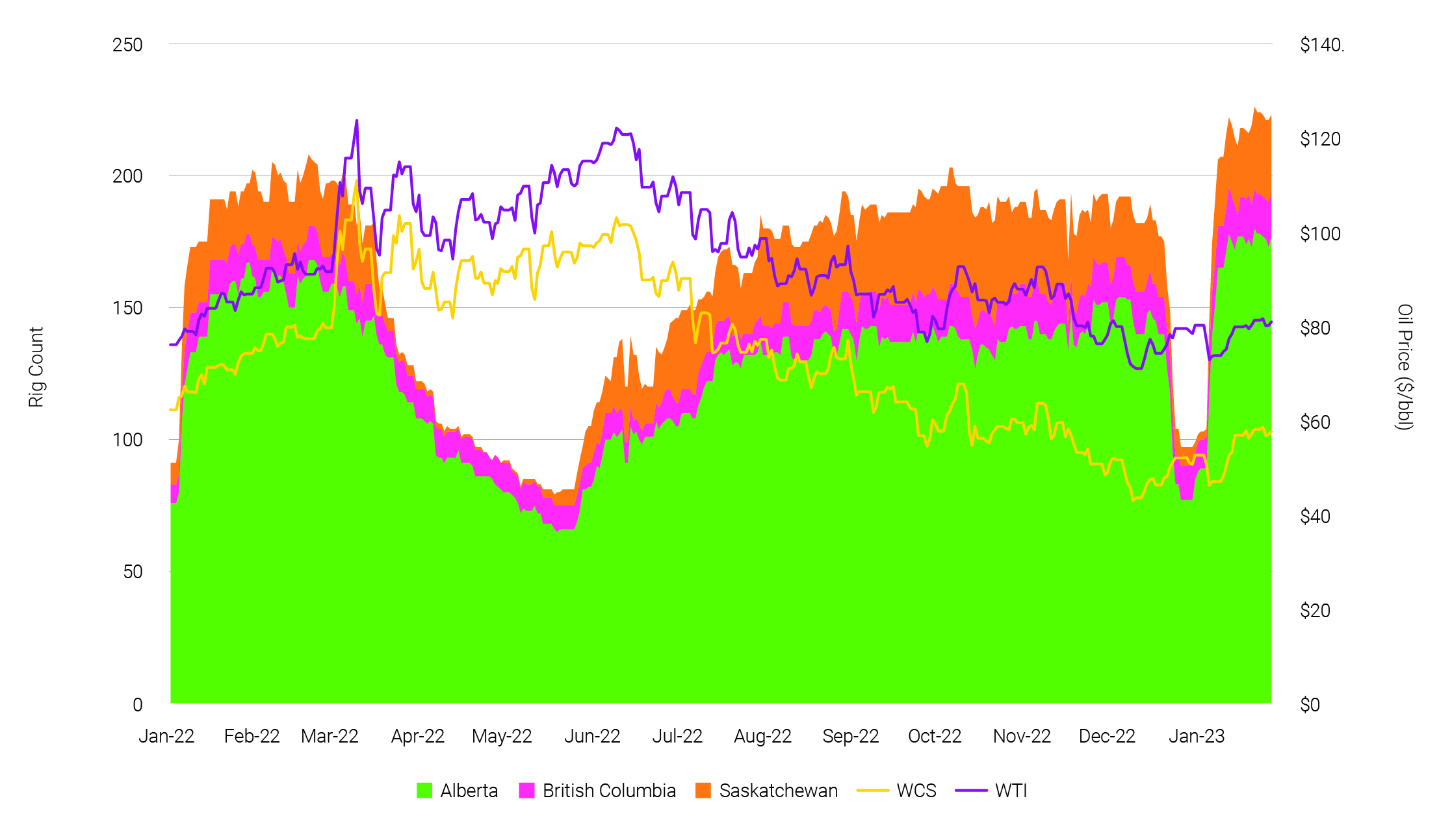

The lion’s share of Canada’s onshore output comes from Alberta, British Columbia and Saskatchewan. Together these three provinces produced almost 4.4 MMbbl/d of oil and 15.5 Bcf/d of natural gas in 2020, according to the Canada Energy Regulator. This accounted for 92% and nearly 100% of the country’s total oil and gas production, respectively, and at a time when Alberta was still imposing oil production restrictions as a result of limited takeaway capacity.

According to recent reports from Enverus Intelligence Research (EIR), gas production in Alberta and B.C.’s Montney play is forecast to grow by about 8.5% annually through 2028, which will lift WCSB output from 17 Bcf/d to 20 Bcf/d. Alberta’s oil sands, which represent about 97% of Canada’s proven oil reserves, are also expected to maintain their historical growth trend through the rest of the decade, reaching 4.2 MMbbl/d by 2030 compared to 3.5 MMbbl/d at the end of 2022.

Upstream M&A activity has also remained healthy in the country. According to Enverus M&A Analytics, there were 83 deals—including royalty transactions—announced last year, including 62 with announced values exceeding $13 billion (C$17.4 billion). While 2021 had more activity at 130 deals, the known aggregate value was lower at $12.7 billion (C$17 billion) from 87 of the deals. Comparatively, M&A activity in the U.S. had a down year in 2022, with $58 billion (C$77.7 billion) from about 150 deals, even fewer than the 170 announced in 2020 and well below the average aggregate value of $74 billion (C$99.2 billion) over the last decade.

Still, difficulties lie ahead for operators to navigate. Some are common with other jurisdictions and some are specific to Canada. Inflationary pressure has been a global phenomenon for the past year or more, and the energy industry has not been immune. In the U.S., overall well costs increased nearly 30% last year, and rig rates rose nearly 48% exit-to-exit, according to EIR and Enverus’ rig day rate data. While different localized factors impact prices in Canadian basins, the macro drivers of high equipment utilization rates, slow supply chains and steady demand for oilfield services should manifest in similar inflation results.

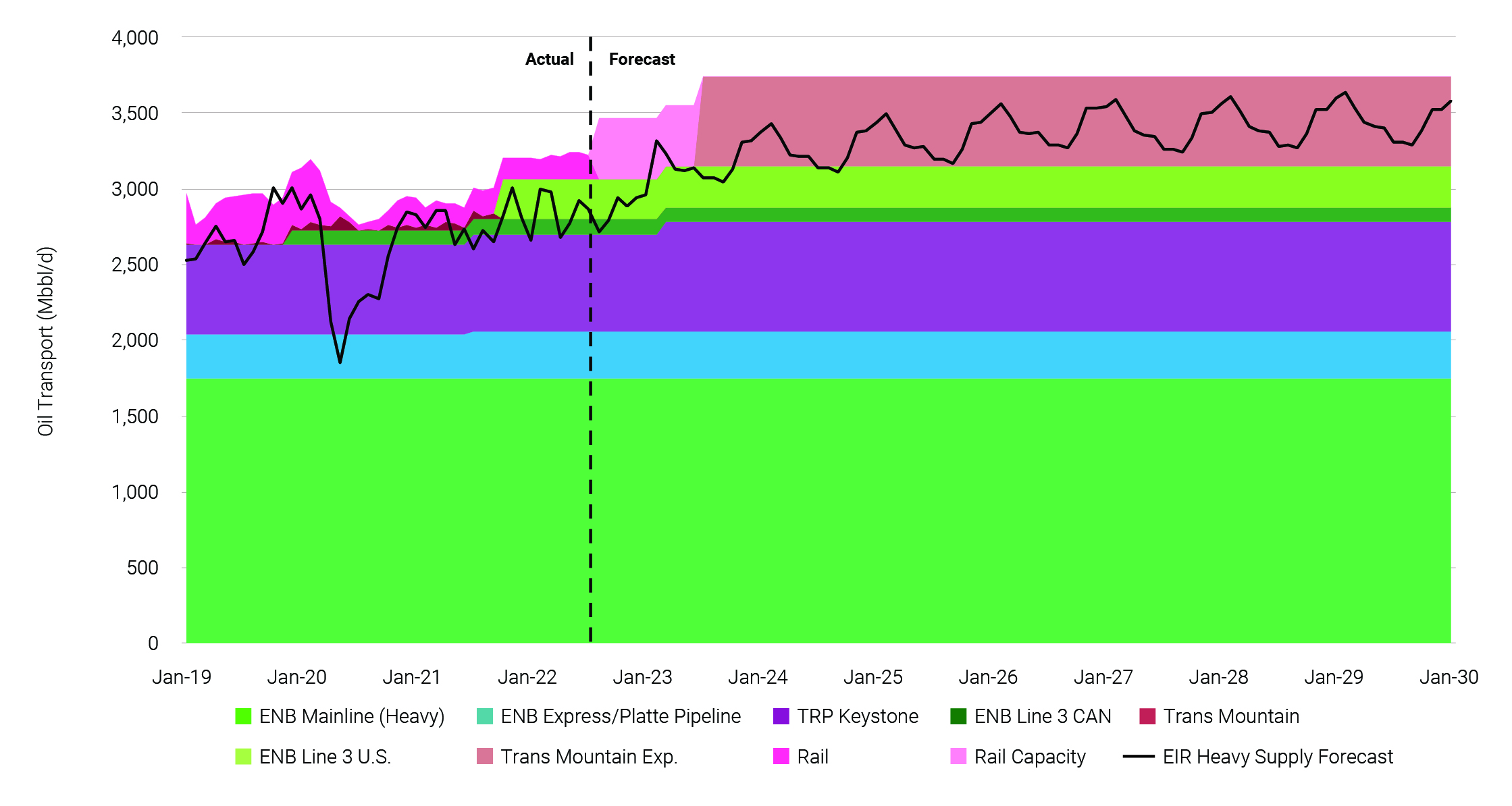

Takeaway capacity has been a concern for several years. A dearth of oil pipeline capacity led Alberta to impose production restrictions that lasted nearly two years, ending only in December 2020 after COVID-19 tanked output. Enbridge’s Line 3 replacement came online in late 2021, doubling its capacity to 760,000 bbl/d, while TC Energy’s 830,000 bbl/d Keystone XL pipeline project was killed. The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project, now expected to begin linefill by the end of 2023, will increase capacity to 890,000 bbl/d from 300,000 bbl/d.

That should give operators some runway through the rest of the decade to get their crude out of the WCSB, but with no new pipelines planned, producers could be forced to limit output or use more expensive rail transport into the 2030s, according to EIR. Gas takeaway capacity in the WCSB has also been an issue at times, as seen in the second half of 2022 with bottlenecks on the Nova Gas Transmission Line (NGTL). While that should be alleviated with additional in-basin demand expected in 2023 and recent NGTL expansions, volatility in the WCSB gas market will likely continue until LNG Canada goes online in 2025.

Emissions are another risk to growth, with the federal government expected to enact a 2030 Emission Reduction Plan early this year. Operators have opposed a draft proposal to reduce sector emissions 42% from 2019 levels by 2030. If such a draft is adopted, the EIR believes it will likely dampen production growth in the absence of wide scale adoption of carbon capture, utilization and sequestration and other mitigation investments.

Several companies and industry groups are already planning carbon sequestration projects, but they may not be enough to meet the 42% target. Alberta selected six proposed carbon capture and sequestration projects last year from its first request for full proposals, including Pembina Pipeline and TC Energy’s Alberta Carbon Grid, Enbridge’s Wabamun hub, Shell’s Atlas hub and others, which together could store over 40 mtpa of CO2 once built. The Pathways Alliance of oil sands producers—which aims to reduce their CO2 emissions by 22 mtpa by 2030—also received approval to begin a detailed evaluation of its proposed $17.9 billion (C$24 billion) carbon storage hub in early January.

New life for struggling offshore

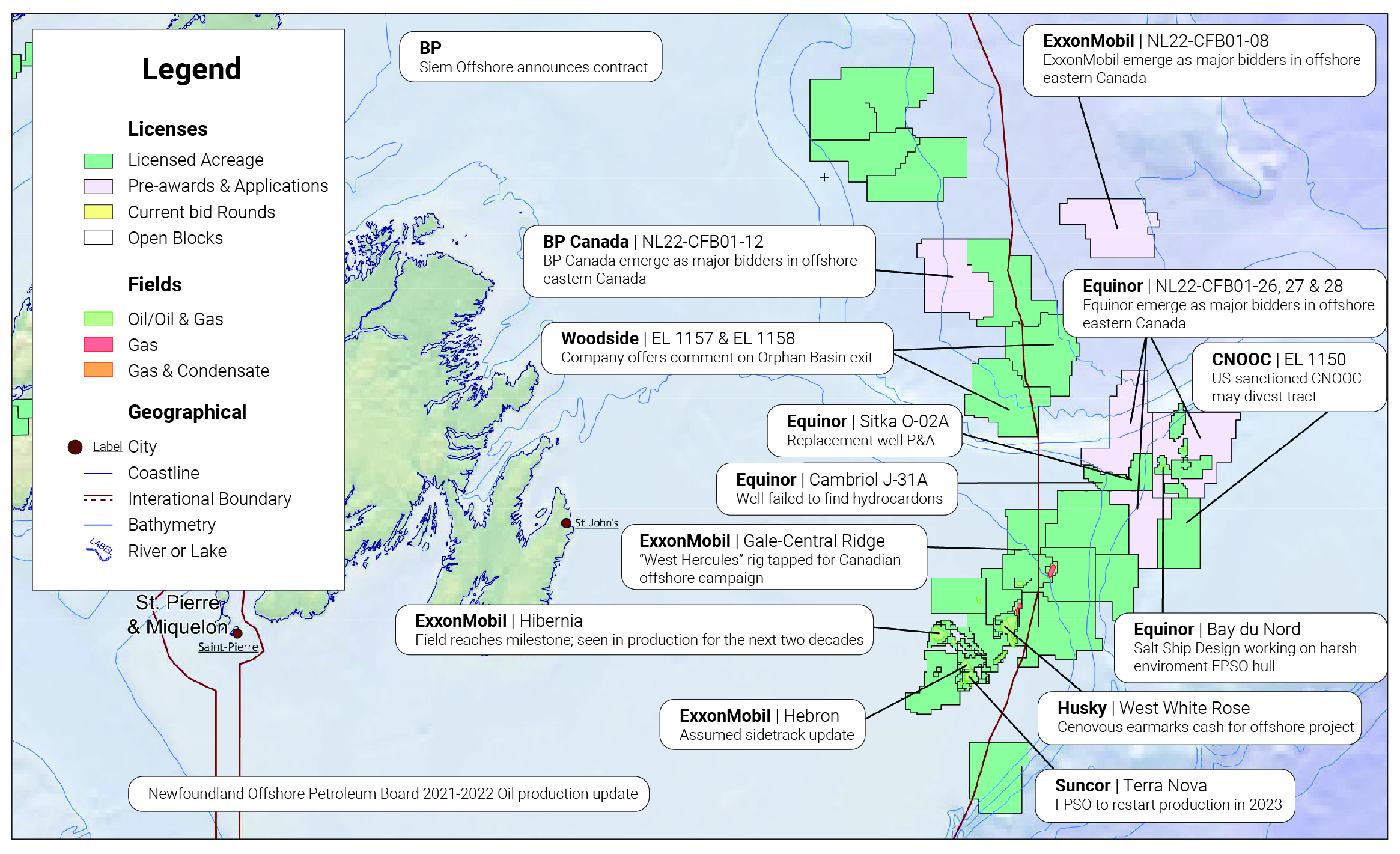

Canada’s other major source of production, although it pales in comparison to the WCSB, is offshore the eastern province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The first offshore development, Hibernia, began production in 1997. It was joined by Terra Nova, Hebron and White Rose and its satellites between 2005 and 2017. In November, the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore and Petroleum Board released statistics showing that the fields averaged nearly 250,000 bbl/d during the 12 months ended March 31, 2022. They produce gas as well, but it is used for power on offshore facilities, reinjected to maintain reservoir pressure or sometimes flared, according to the Canada Energy Regulator.

The region has had its fair share of struggles in recent years. The C-NLOPB ordered Suncor to halt operations at Terra Nova in late 2019—months after the project partners had first sanctioned a life extension project—following a series of safety and regulatory noncompliance issues. One of those issues resulted in charges being laid against Suncor last December for a December 2019 injury onboard the FPSO. The life extension project faced cancellation but was saved at the 11th hour in the second half of 2021 following a restructuring of the project. Terra Nova is now expected to resume production in the first quarter of 2023.

The West White Rose project, now operated by Cenovus following its acquisition of Husky Energy, was suspended in 2020 following the oil price crash. Work only resumed last year, and it is not expected to deliver first oil until the first half of 2026.

The ExxonMobil-led Hibernia project suffered a two-month shutdown in 2019 following an oil spill. That stoppage was extended after the first attempt to resume production, when a power loss caused the firefighting deluge system to release water, overflowing drain tanks and releasing more oil into the ocean.

The only major new project currently planned is Equinor’s Bay du Nord hub. The Norwegian operator temporarily suspended planning work in 2020, but it made new discoveries at Cappahayden and Cambriol later that year and is now working on developing a larger project. Canadian regulators approved an environmental assessment last year, but several environmental groups filed a lawsuit seeking to halt the project. In late January, the company reportedly issued a notice to potential offshore contractors to submit an expression of interest in relation to the project’s planned 200,000 bbl/d FPSO.

Equinor and partner BP also picked up three licenses adjacent to Bay du Nord late last year in C-NLOPB’s 2022 bid round. Although the regulator offered 28 different parcels covering over 7 million hectares with a minimum work commitment of $7.5 million (C$10 million), only five bids were ultimately successful. ExxonMobil was the standout, bidding $135.5 million (C$181.6 million) for the 267,686-hectare Parcel 8. The remaining four successful bids had work commitments ranging from $8.1 million to $12.3 million (C$10.8 million to C$16.5 million).

Recommended Reading

CEO: Continental Adds Midland Basin Acreage, Explores Woodford, Barnett

2024-04-11 - Continental Resources is adding leases in Midland and Ector counties, Texas, as the private E&P hunts for drilling locations to explore. Continental is also testing deeper Barnett and Woodford intervals across its Permian footprint, CEO Doug Lawler said in an exclusive interview.

To Dawson: EOG, SM Energy, More Aim to Push Midland Heat Map North

2024-02-22 - SM Energy joined Birch Operations, EOG Resources and Callon Petroleum in applying the newest D&C intel to areas north of Midland and Martin counties.

Chevron Hunts Upside for Oil Recovery, D&C Savings with Permian Pilots

2024-02-06 - New techniques and technologies being piloted by Chevron in the Permian Basin are improving drilling and completed cycle times. Executives at the California-based major hope to eventually improve overall resource recovery from its shale portfolio.

Texas Earthquake Could Further Restrict Oil Companies' Saltwater Disposal Options

2024-04-12 - The quake was the largest yet in the Stanton Seismic Response Area in the Permian Basin, where regulators were already monitoring seismic activity linked to disposal of saltwater, a natural byproduct of oil and gas production.

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for Second Week in a Row

2024-01-26 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by one to 621 in the week to Jan. 26.