Subsea boosting as a means of achieving improved oil recovery (IOR) has been around for some time, though uptake has been limited.

Players in the space, including FASTsubsea—a joint venture (JV) between Aker Solutions and Fsubsea—hope the innovations they are introducing will encourage wider adoption of the technology.

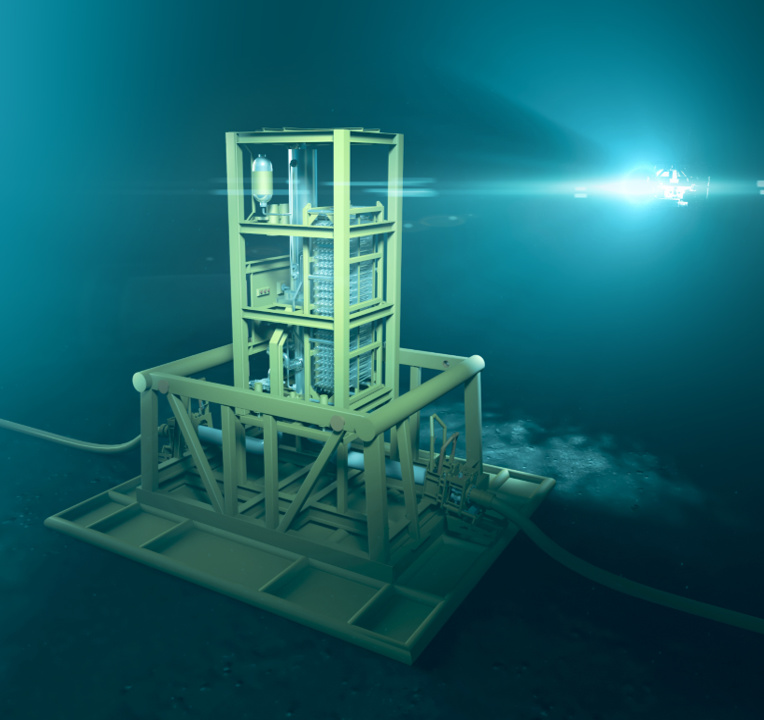

FASTsubsea is developing the world’s first topside-less subsea multiphase boosting system, which is known as FASTsubsea X. The technology is targeted at increasing oil recovery from brownfield projects, tie-backs and marginal or distributed fields, enabling boosting where there is no available topside space. This approach is expected to help cut costs, save time and reduce CO₂ emissions.

Fsubsea founder and CEO Alexander Fuglesang touted increased recovery from existing fields or from tie-backs as a positive, especially given current market conditions coupled with increased ESG requirements.

“This can really support an orderly transition to a more green economy,” he told Hart Energy, noting that most new discoveries on the Norwegian and U.K. continental shelves are close to existing infrastructure.

FASTsubsea’s plans recently received a boost on news that Equinor and Vår Energi had joined Malaysia’s Petronas in a joint industry program to qualify and test its technology.

The program is scheduled to start testing in the fourth quarter of 2023 and finish in the first half of 2024, with a technology readiness level (TRL) of 4 according to the API scale, “which most clients deem sufficient for being qualified for a project,” Sigmund Rasmussen, Aker’s senior manager for pump technology, told Hart Energy.

“In parallel, we are engaging in studies and discussing various ocean pilot projects,” Rasmussen said. “Some clients are discussing piloting projects to bring the maturity to TRL-5 (API), which is possible when you have a concrete project specification.”

The extent to which FASTsubsea’s pumps will boost recovery once deployed will depend on a number of factors.

“This is highly field-specific, as it relates to well pressures, gas-fluid mixes, viscosities, etc,” Fuglesang said. “However, there are estimates and examples on this from other subsea-boosting projects, which also will apply to our technology. The general range is typically from 10%-30% IOR.

“Simply put, for every 1% increased recovery from a, say 200 million-barrel field, the economic opportunity is $200 million if every barrel sells for $100,” Fuglesang continued. “To put this in the context of costs, the typical target cost for new subsea-boosting projects is $50million-$100 million per project, where about one-third is installation and marine operations.”

He cited the recent example of Equinor’s Vigdis subsea-boosting project, which was publicly announced at around $140 million of capex costs, with about 475 million barrels still recoverable.

Encouraging uptake

There are a number of fields around the world where subsea-boosting could be deployed. Consultancy Rystad Energy told Hart Energy that under its current base case, 240 projects globally could benefit from installing boosting, with brownfield opportunities accounting for 139 of those and greenfield developments making up the remainder.

FASTsubsea’s own analysis, using data from Rystad, suggests that out of more than 5,000 active offshore wells with average recovery rates below 35%, around 1,500 are at a stage where they can benefit from subsea boosting.

“The demand seems solid,” Rasmussen said, adding that often one pump can boost a cluster of two to six wells.

Obstacles to the more widespread adoption of subsea boosting include concerns over cost, complexity and reliability.

“We are hoping that our much more simple FASTsubsea boosting system will come in at lower cost compared to existing solutions and lead to more widespread adoption,” Rasmussen said.

And as efforts to decarbonize the oil and gas industry accelerate, FASTsubsea will hope that its emissions credentials will also give it an edge.

“The competitor to subsea boosting is typically gas injection. This approach typically carries more than twice the CO₂ footprint,” Rasmussen said. “Most of our customers care about lowering the CO₂ emissions for each barrel produced. We can help with that, with boosting using 60%-80% less energy—and hence lower CO₂ emissions—than gas lift for recovering the same barrel of oil.

“Besides,” he added, “these days the gas is expensive and better used for electricity or heating.”

Compared to other boosting systems, FASTsubsea also promotes the benefit of having the first all-electric system, so there are no hydraulic oils or chemicals, and it does not require any topside space or equipment.

“The latter significantly reduces costs, but also the initial, often considerable ‘one-off’ CO₂ footprint related to designing, producing and installing the equipment,” Fuglesang said.

Market conditions look favorable, given the focus on decarbonization and the fact that offshore operators remain concerned about cost savings and maximizing recovery. If the testing of its technology goes as planned, FASTsubsea will be on course to introduce its technology to even more operators.

“The main challenge is to get the first real field implementations and encourage wider adoption—same as other players who are introducing new technology to a conservative space,” Fuglesang said.

Recommended Reading

Trio Petroleum to Increase Monterey County Oil Production

2024-04-15 - Trio Petroleum’s HH-1 well in McCool Ranch and the HV-3A well in the Presidents Field collectively produce about 75 bbl/d.

US Drillers Add Most Oil Rigs in a Week Since November

2024-02-23 - The oil and gas rig count rose by five to 626 in the week to Feb. 23

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for Second Time in Three Weeks

2024-02-16 - Baker Hughes said U.S. oil rigs fell two to 497 this week, while gas rigs were unchanged at 121.

US Gas Rig Count Falls to Lowest Since January 2022

2024-03-22 - The combined oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by five to 624 in the week to March 22.

Sangomar FPSO Arrives Offshore Senegal

2024-02-13 - Woodside’s Sangomar Field on track to start production in mid-2024.