Source: Shutterstock.com

HOUSTON—U.S. shale oil and gas production could grow to about 27 million barrels, accounting for 25% of the global market share through the 2030s, according to the CEO of Rystad Energy.

If financial barriers were removed, producers could push the number higher, Jarand Rystad, founder of the energy consultancy firm, told attendees of a recent forum. This is despite cash flow returns being negative—massively negative.

“It’s a long, long growth story and of course, that growth story requires a lot of cash,” Rystad said, later pointing out how shale developments essentially killed talk of Arctic exploration in the U.S. and impacted expectations for growth offshore.

With improved technology and techniques, shale players have pumped higher concentrations of proppant and fluid, tinkered with cluster spacing and drilled longer laterals to get more oil from reservoirs while bringing down costs.

“From 2016 it has halved the average breakeven price and the volumes have almost doubled,” Rystad said of the shale industry. He added that access to in-basin sand has been a driving factor over the last year.

But with skittish investors, a push toward cleaner sources of energy and the threat of having social licenses to operate revoked, will the projected shale growth come to fruition?

Panelists participating in the forum co-hosted by the firm and Pareto Securities shared their thoughts.

“The growth is possible if you take a look at the prospects,” said Nicole Baird, asset manager for Equinor. “One of the reasons why we’re seeing the growth is it’s not about well count. It’s lateral length,” which has grown by nearly 140% over the last four to five years for Equinor. It’s not uncommon to hear about shale wells with lateral lengths of 15,000 ft to 17,000 ft, she added. “What it really allows you to do is to reduce that well count.”

Couple that with drilling efficiencies and “all of a sudden these wells are becoming incredibly prolific and highly profitable,” Baird said.

She earlier pointed to the rise of unconventional gas in the Appalachian Basin, where she said industry production has grown from about 2 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) 10 years ago to about 28 Bcf/d today. “That is actually more than what’s produced off the Norwegian Continental Shelf,” Baird said, adding Appalachia production is projected to reach 42 Bcf/d by 2027.

Ian Bryant, CEO of completion technologies-focused Packers Plus Energy Services, added, “the spectacular growth in shale shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone.” Looking back to the early part of the century, Bryant said the industry was dealing with very low permeability rock with six to eight fracs per well.

“Through the evolution of technology and techniques and learning about it, we’re now at a stage where we can grow very long laterals, put in much more fracs and higher proppant loading and do it economically,” Bryant said. But “I think it will be more difficult to sustain that growth going forward.”

Challenges Ahead?

Offshore players on the panel also weighed in on the topic.

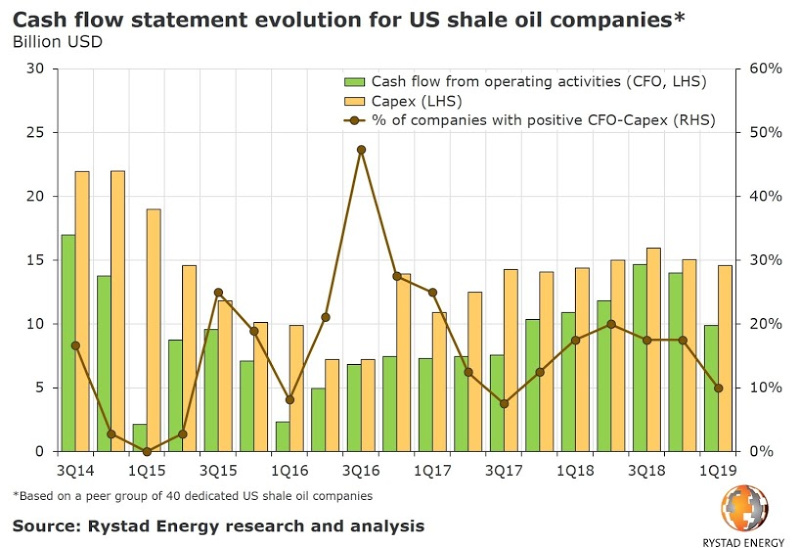

Looking at how some U.S. shale players’ capex has consistently outstripped cash flow from operations quarter after quarter, Transocean CEO Jeremy Thigpen questioned how long that would last.

“That doesn’t strike me as a sustainable business model. … Is it technically possible for unconventionals to continue to grow? I guess,” said an admittedly biased Thigpen, head of an offshore drilling company with a fleet that includes more than 50 floaters. “But until something happens with the business model, I don’t know how you keep investing money into a business where you’re investing more than you’re pulling out.”

But Rystad pointed out how companies are reinvesting in the shale business, which is actually yielding a 25% internal rate of return. “Then you can choose yourself as an investor whether you want to return that cash back to the industry or keep it for yourself,” Rystad said. However, he added, that management of companies are free to reinvest in the company, which is perhaps worrying investors.

Earlier in the panel discussion, Independence Contract Drilling CEO Anthony Gallegos mentioned the need for more information on declines and depletion rates, and he highlighted how the industry has been laying down land rigs.

The U.S. land rig count dropped to 939 the week of June 21, compared to 1,052 a year earlier, according to Baker Hughes, a GE company. Many E&Ps are cutting spend to focus more on shareholder returns and paying down debt. Rigs have also become more efficient.

“I can say from the industry perspective to continue the kind of growth momentum that we’ve enjoyed over the last half decade will be a challenge—no doubt about it,” Gallegos said. “Service costs are not sustainable. The same pressure that our customers have been under for the last couple of years to focus on returns, free cash flow, that attention now is directed at oilfield services. Certainly, we as public companies have to be very mindful of that.”

If the maintenance capex required to run a fleet of drilling is truly considered, “service costs must go up and will have to go up, or we’re not going to have a service industry to drill the wells.”

Plus, well density and communication between wells, or parent-child relationships, is a “much bigger issue than is understood today and I think it will continue to be a bigger issue,” Gallegos added. “That’s going to have an implication on the number of wells that ultimately can [be] drilled.”

Then, there is a movement pushing toward renewable forms of energy, despite the widespread use and need for oil and gas. A few states, including New York, have already banned hydraulic fracturing.

Panelists seemed to agree with Baird, who said it’s up to the industry to be prudent operators and service companies. If something does happen, it will be an issue for the entire industry not just an individual company, she said.

Gallegos added that he’s confident the industry will maintain its social license.

“We never were as bad as people thought but I know today we are much better than we’re given credit for,” he said. “We work hard every day to protect people, protect the environment and respect the communities that we’re in.”

Looking Offshore

The conversation took place as the offshore sector regains strength following a slowdown in spending. The sector saw players exit, opting to pursue onshore shale developments. But strides are being made offshore in many parts of the world.

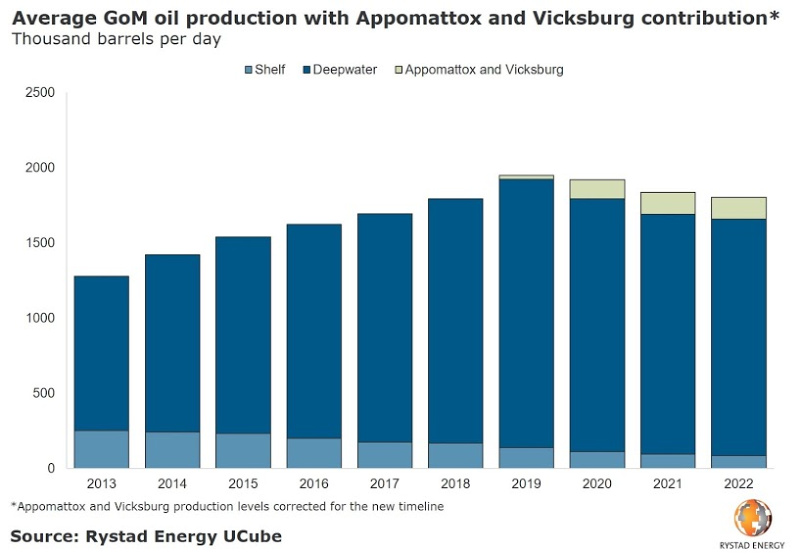

Take the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GoM), for example. Royal Dutch Shell recently started producing oil and gas at its Appomattox deepwater platform, marking the first production from a Jurassic-aged reservoir in the GoM. Last year several private-equity-backed players jumped into the GoM action. In addition, sanctioning is picking up and offshore companies are driving down costs, including through use of existing infrastructure and subsea tiebacks.

Subsea Infrastructure Partners, formed about a year ago, is partnering with operators in the GoM to help monetize existing infrastructure and improve field economics, according to David Russell, chairman of the midstream company.

“Oil companies get very little value for their infrastructure,” Russell said, noting it’s reserves and production that typically add value.

But infrastructure enables it.

“I will say that the lifting costs of very compelling,” for projects involving tiebacks and existing infrastructure, Russell said.

Customers are more encouraged than they were 12 months ago, Thigpen added. He said there is also more conversation around offshore exploration, day rates are improving and so are project economics.

“The returns are pretty good at today’s oil prices,” Thigpen said.

But that hasn’t translated to a higher share price. “Our share price is trading at about half of what it was this time last year.”

That’s something to which shale-focused companies can also relate.

Packers Plus’ Bryant said the value of reserves to an oil company is missing from the shale and offshore discussion. That is what drives the value of companies, he said.

“Companies like Shell, Exxon Mobil and Chevron have sunk hundreds of millions of dollars into making discoveries which currently are not being exploited,” Bryant said.

Going forward, bringing some of those offshore developments online will be key, he added, though shale is currently still in the forefront.

Velda Addison can be reached at vaddison@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

Exclusive: Chevron Balancing Low Carbon Intensity, Global Oil, Gas Needs

2024-03-28 - Colin Parfitt, president of midstream at Chevron, discusses how the company continues to grow its traditional oil and gas business while focusing on growing its new energies production, in this Hart Energy Exclusive interview.

Imperial Expects TMX to Tighten Differentials, Raise Heavy Crude Prices

2024-02-06 - Imperial Oil expects the completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion to tighten WCS and WTI light and heavy oil differentials and boost its access to more lucrative markets in 2024.

Carlson: $17B Chesapeake, Southwestern Merger Leaves Midstream Hanging

2024-02-09 - East Daley Analytics expects the $17 billion Chesapeake and Southwestern merger to shift the risk and reward outlook for several midstream services providers.

Midstream Builds in a Bearish Market

2024-03-11 - Midstream companies are sticking to long term plans for an expanded customer base, despite low gas prices, high storage levels and an uncertain political LNG future.

Exclusive: Renewables Won't Promise Affordable Security without NatGas

2024-03-25 - Greg Ebel, president and CEO of midstream company Enbridge, says renewables needs backing from natural gas to create a "nice foundation" for affordable and sustainable industrial growth, in this Hart Energy Exclusive interview.